The great changes that have occurred in the job world in recent decades have made the experts argue that the nature of current work is closely related to the social context it is a part of (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Oldham & Hackman, 2010). In line with these developments, Humphrey et al. (2007) proposed a theoretical model of work characteristics that considers four social characteristics of work (feedback received, interaction beyond the organization, job interdependence and social support), besides the motivational aspects of the job Hackman and Oldham (1976) described earlier. In addition, in the meta-analysis by Humphrey et al. (2007) it was shown that the social characteristics did not overlap with the non-social characteristics, and consequently explained significant additional variance rates in work satisfaction, organizational commitment, performance and turnover when compared with the latter.

These results expose the need to develop future studies, which are capable of contributing to the advancement of knowledge on the effects of social and specific relational characteristics on different work outcomes, such as employee performance and wellbeing, as argued by Oldham and Hackman (2010). The social resources most frequently addressed in the empirical studies thus far have been the different types of support provided by co-workers, the supervisor or the organization (Bakker, 2022; Pérez-Nebra et al., 2022). To contribute to the completion of this gap, this study focuses on a social characteristic of work, which is the feedback that the other organizational members received, and one of its objectives is the identification of the relationship between the feedback received and the performance of work roles. Other people’s feedback can be considered as the extent to which the individuals in the organization provide information about performance from co-workers, supervisors and clients (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006).

Another issue the experts on work characteristics have raised refers to the psychological processes responsible for the relation between the social characteristics of work and the work outcomes, particularly regarding the worker’s internal motivation (Oldham & Hackman, 2010). In this study, to address that issue, the Job Demands-Resources Theory (JD-R) will be used (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b).

The JD-R theory can be considered an extension of the more traditional job characteristics models. According to that theory, the work characteristics can be classified in two different categories: work demands (characteristics of the work context that drain the employee’s energy and lead to burnout) and resources (characteristics of the job context that stimulate the employee’s development and lead to his engagement at work, a motivational condition that consequently contributes to his better in-role and extra-role performance as well as to the organizational performance (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b; Lesener et al., 2020; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2009; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

Feedback is characterized as a job resource that plays an intrinsic motivational role (individual’s basic needs), as well as an extrinsic motivational role (information that makes it easier to control one’s own actions and achieve targets smoothly) (Ryan et al., 2021a, 2021b). Anseel et al. (2015, p. 326) posit that feedback at work helps people “gain greater clarity about how things work in the organization and what others expect of them”. Prior research anchored in The Social Cognition Theory (Bandura, 1991) has generally assumed that feedback is important for improving in-role performance. Controlled action, with instructive feedback, serves as a vehicle for converting conceptions into proficient performances. Theory can be useful for our understanding since it is indicated in social applications, as is the case with organizations.

From the perspective of the JD-R theory (Bakker et al., 2023a), labor resources are the main predictors of labor engagement (Bakker, 2022; Lesener et al., 2020; van Veldhoven et al., 2020), a work-related affective-motivational state of well-being, manifested in feelings of vigor, dedication and absorption in work (Salanova et al., 2000; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2009; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2023). Job resources foster the emergence of work engagement, as they have motivational potential (Lesener et al., 2020; Lesener & Taris, 2014). In this sense, they satisfy the basic needs of autonomy, competence and relationship, in accordance with Self-Determination Theory (Ryan et al., 2021a, 2021b). These resources also increase the likelihood that employees will achieve their work goals, because more resource-intensive work environments motivate employees to do more to accomplish their tasks, increasing engagement in their work (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

One important contribution of JD-R Theory to the motivational process was the inclusion of personal resources as antecedents of positive phenomena, such as well-being (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b; Hobfoll et al., 2018; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Personal resources as self-positive assessments make the individuals more able to control and influence their environment, which leads them to become more committed to setting goals and striving to achieve them, which is why they end up showing a better role performance in the workplace (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). The personal resources related positively to the work engagement (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b). In a recent meta-analysis on antecedents of engagement, the authors found that the effect size of personal resources was greater than that of work resources (Mazzetti et al., 2023).

In this study, authentic living was included as a personal resource capable of eliciting work role performance and engagement. Authentic living refers to the degree to which the person is true to himself in most situations, behaving and expressing himself in a way that is consistent with his or her emotions, beliefs and opinions (van den Bosch & Taris, 2013). Authentic living can be considered a personal resource because it is the coherent expression of the individuals according to their emotions, beliefs and opinions. For when the individual appears to be more authentic, he usually experiences more positive and achieving states at work (van den Bosch & Taris, 2013). Authenticity has been shown to be a positive predictor of manifest psychological phenomena in the job context, such as job well-being (Sutton, 2020).

According to Bakker et al. (2023a; 2023b), work engagement leads the employee to experience more positive emotions, to create more job and personal resources, and to transfer his or her engagement to other co-workers. Recent research findings using self-storytelling strategies found that positive emotions were more present among highly engaged employees (van Roekel et al., 2024). The finding that highly engaged employees use the first-person plural more is a tangible indication of the social and contagious nature of work engagement (Bakker, 2022). Thus, work engagement is associated with indicators of well-being (organizational commitment, job satisfaction and quality of life (Salanova et al., 2000; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2009). This motivational state is also responsible for a more favorable perception of work, which empowers employees to strive for better quality performance (Corbeanu & Iliescu, 2023; Neuber et al., 2021; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Such an argument finds support in Fredrickson's Broaden-and-Build Theory (2001), according to which the experience of positive emotions momentarily expands the individual's repertoire of thoughts and actions, that is, it causes him to consider more alternatives in any situation. As a result, he becomes more proactive, which is reflected in his better performance at work (Corbeanu & Iliescu, 2023; Neuber et al., 2021; Peñalver et al., 2023; van Roekel et al., 2024).

Self-Determination Theory also helps to explain the association between work engagement and performance (Peñalver et al., 2023; Ryan et al., 2021a, 2021b). According to this theory, the fact that the individual finds himself intrinsically motivated for an activity leads him to perceive it as more interesting, pleasant and satisfying, which causes him to strive to perform better, insofar as it satisfies their basic needs for competence, relationship with others and autonomy.

In addition, the JD-R Theory presupposes that the motivational potential of certain job characteristics results in certain outcomes through work engagement (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b; Corbeanu & Iliescu, 2023; Neuber et al., 2021). Work engagement has acted as a mediator of the relations between various work resources and different individual and work outcomes (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Thus, for example, job control and coworker social support relate to employee work engagement, which in turn relates to personal initiative linked with idea implementation (i.e., sequential mediation) (Massei et al., 2022); and job resources were positively related to work engagement, which in turn, was negatively related to turnover intention (Kawada et al., 2024).

The motivational nature of personal resources, however, is similar to that of work resources though, and are thus also positively related to work engagement, which in turn is associated with work performance (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Thus, a recent study has demonstrated weekly proactive vitality management was positively related to changes in weekly creativity through changes in weekly work engagement (Bakker et al., 2020). In addition, the mediating role played by work engagement in the relationships between self-esteem and work ability has been demonstrated (Airila et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the available empirical evidence reveals that personal resources have been integrated in the JD-R Theory in different manners: as direct antecedents of engagement; as a mediating variable of the relationships between work characteristics and engagement; as a moderating variable of these relationships, as an antecedent of the job characteristics; as a third variable that explains both the engagement and the job characteristics and that can thus explain the relationship between both (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Therefore, the role of personal resources in the JD-R Theory is not clear yet and the results can vary in function of the specific combination of personal resources, work characteristics and attitudinal or behavioral results considered in each study (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). In other words, one of the limitations in that theory has been the fact that, thus far, it neglected the clarification of more specific relationships between the job resources, personal resources and their consequences (Airila et al., 2014).

Personal resources, by definition, can mitigate the negative effects of job demands or enhance the positive effects of job resources on engagement (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Research on the moderating role of personal resources in the context of the JD-R Theory, however, has prioritized the interaction of such resources with the work demands, i.e. with the ways in which personal resources cushion the negative effects of those aspects of the job context that require efforts on the part of the individuals and, consequently, generate tensions and other physical and psychological costs (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b). Thus, for example, the satisfaction of compassion (personal resource) cushioned the impact of job demands (burden) on anxiety and depression (Tremblay & Messervey, 2011).

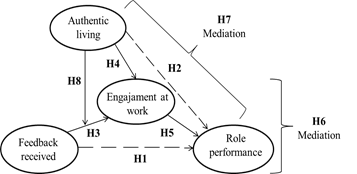

To postulate that authentic living moderates the relationship between feedback received and engagement also implies that authentic living moderates the indirect relationship between feedback received and work performance. Thus, it is expected that the effect of the feedback received on role performance, through engagement, is greater among employees with higher levels of authentic living. In other words, authentic living is seen in the present model as a facilitator of the positive effects of both feedback received and work engagement on job performance. Therefore, the present model is characterized as a moderate mediation model, in which the effect of an independent variable (feedback received) on a dependent variable (performance of work roles), as well as the effect of a mediating variable (work engagement) on the dependent variable (role performance) depends on the level of another variable (authentic living). Considering such statements, the following hypothesis were formulated:

Hypothesis 1: The feedback received is positively associated with work role performance.

Hypothesis 2: Authentic living at work is positively associated with work role performance.

Hypothesis 3: Feedback received is positively associated with work engagement.

Hypothesis 4: Authentic living at work is positively associated with work engagement.

Hypothesis 5: Work engagement is positively associated with the performance of work roles.

Hypothesis 6: Work engagement mediates the relationship between the feedback received and the performance of work roles.

Hypothesis 7: Work engagement mediates the relationship between authentic living and the performance of work roles.

Hypothesis 8: Authentic living at work moderates the relationship between feedback received and work engagement, so that the relationship is more positive when the level of authentic living is higher.

Hypothesis 9: Authentic living at work moderates the indirect relationship between the feedback received and the performance of work roles, through work engagement, so that the indirect relationship is more positive when the level of authentic living is higher.

This study offers some contributions to the literature. First, it contributes to the extension of the traditional theories on work characteristics by changing the traditional focus of these theories by focusing on the role the social characteristics play in work outcomes. Second, it contributes to the extension of the JD-R theory by validating an integrated model that deepens the understanding about the psychological mechanisms through which the social and personal resources explain the performance at work. Third, the investigation of a personal resource not addressed in earlier studies, playing a moderating role of effects of the job context on work outcomes, also contributes to the extension of the empirical results on the ways through which personal resources mold the conditions needed for the effects to take place from the perspective of the JD-R Theory. Finally, deepening the understanding of the complex nature of the relationships between the social resources and individual performance can also be useful to managers and human resource professionals in the implementation of practices that stimulate the social relationships, as a way to enhance the organizational members’ performance. Therefore, in this investigation, we tested the model presented in Figure 1

Figure 1: Research model representing the proposal of combined effects of the feedback received and the authentic living on engagement and performance

Materials e methods

Participants

Based on a convenience sample, 1244 Brazilian workers responded to the self-reported questionnaire during the second half of 2015. The inclusion criterion was having at least one year of work experience at the time of the data collection. The sample exclusion criteria were related to absence from work, whether due to being retired, on leave (e.g. maternity leave) or on vacation. Participants who had any condition that would impede self-completion of the instruments (e.g. visual impairment) were also excluded. The survey included the participation of workers from 21 Brazilian states, with emphasis on respondents from Minas Gerais (29.9 %), followed by Rio de Janeiro (16.6 %), Santa Catarina (6.3 %) and Rio Grande do Sul (6.1 %). Participants were mainly males (58.5 %), mean age of 36.23 years (SD= 9.93), and most of them have a college degree (65.7 %). They came mainly from public organizations (72.1%), but also worked in private companies (27.9 %). Their work time ranged from 1 to 36 years, with an average time of 6.23 years (SD = 6.35). They are mainly enrolled in administrative or operational functions (75.2 %). As for the activity branch of the organization, the highest percentage was active in the field of education (66.7 %).

Procedures

The researchers contacted the organizations by e-mail (using internal communication channels) and face-to-face meetings (through a face-to-face and individual approach of the participants), totaling around 20,000 invitations. The organizations were selected through the indication of professionals who participated in previous investigation with the researchers. In the online application, initially, a brief explanation was provided about the objectives of the research, followed by a link that led directly to the initial screen of the research. The questionnaire in a Word file was also forwarded to the participants who manifested their willingness to respond in electronic format and later re-send the file to the researchers. In the face-to-face application, the workers initially read the instructions, filled out the questionnaire and returned it to the researchers. Nine hundred and thirty-six participants answered the questionnaire electronically, through the link sent. Three hundred and eight individuals personally answered the questionnaire. In all situations, the respondents were informed about the anonymity of their answers.

Instruments

The feedback received was assessed based on three items from the 'Social Characteristics' scale of the Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ) (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). The items were rated on a seven-point Likert frequency scales ranging from one (never) to seven (always). Example item: "I get feedback about my performance from others in my organization, such as my manager or co-workers".

Work engagement was measured using the reduced Brazilian version of the Work Engagement Scale (Ferreira et al., 2016), adapted from the Utrecht Engagement Scale (UWES) by Schaufeli et al. (2006). The instrument consists of nine items, to be answered on seven-point Likert frequency scales, ranging from one (never) to seven (always). An example item is "I feel happy when I work hard."

To evaluate the performance of work roles, six items of the scale developed by Griffin et al. (2007) were used, to be answered on seven-point Likert frequency scales, ranging from one (never) to seven (always). Example item: "I helped my co-workers when asked or as needed".

Authentic living was investigated through the subscale of the short version of the Scale of Individual Authenticity at Work, developed by van den Bosch and Taris (2013) and adapted to the Brazilian context by Chinelato et al. (2015). It is composed of four items, to be answered on seven-point Likert scales, ranging from one (fully disagree) to seven (fully agree). Example of item: "I behaved according to my values and beliefs".

Data analysis

Structural equations modeling was used to evaluate the research model. All study variables were set as latent. The moderations were investigated based on latent interactions implemented in the software Mplus, version 8. The parameters of the structural equation models were estimated using the Robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) method, which was robust to the violation of the assumption of normal distribution. The indirect effect was tested through the bootstrap (1000 samples). The research hypotheses were tested in three steps. In the first stage, the direct relationship between feedback received (IV) and role performance (DV) was tested, as well as between authentic living (IV) and role performance (DV). The second step consisted in adding the work engagement as a mediator variable of the two relationships between IV and DV. Finally, in the third step, we tested the moderation effect of authentic living on the relationship between feedback and engagement. In this last step, the latent interaction between authentic living and feedback was inserted into the model.

Ethical considerations

The procedures adopted in this research followed the ethical guidelines provided for in the resolutions of the National Health Council (CNS) N. 510/2016 and 466/12, which deal with ethical precepts and the protection of research participants. The research project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Salgado de Oliveira University, Niterói-RJ, Brazil (Protocol No. 465548). During data collection, participants had access to the Free and Informed Consent Form, in which they were informed about their free and spontaneous participation and could withdraw their consent or interrupt participation at any time. In this way, the ethical principles of voluntary participation and anonymity of responses were respected.

Results

Measurement Model

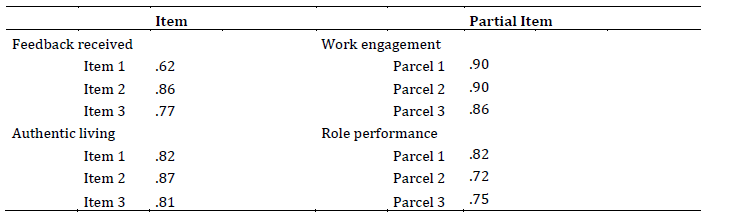

To evaluate the internal structure and the discriminant validity of the scores, confirmatory factorial analysis was performed modeling four latent variables (feedback received, work engagement, role performance and authentic experience). To estimate the models, partial items were created from the engagement and performance scales (Table 1). To compose the parcels, the correlations between the items were considered, and we tried to maintain, in each parcel, items with different intercepts (to guarantee the variability of the endorsement likelihood in each partial). The use of parcel items is justified due the quantity of parameters to be estimated in a latent moderation model. Regarding to the authentic living scale, initially consisting of four items, the item "I found it easier to relate to people from my place of work when I was being myself" was excluded due to a non-significant factor loading (p≥ .05). The four-factor model of latent variables indicated an adequate fit to the data with χ²(df) = 209.06 (48); TLI = .96; CFI = .97; RMSEA (90% CI) = .05 (.05-.06).

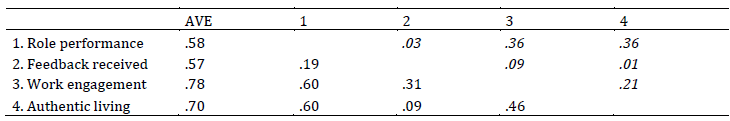

To broaden the analysis of the measuring model, the average variances extracted (AVE) from the variables under study were calculated (Table 2). For the scales, the mean factor loadings were equal to or greater than .57 and higher than all determination coefficients (i.e., squared correlations), yielding evidence of discriminant validity.

Table 2: Correlations, Determination coefficients and AVE

Note: In the lower diagonal, the correlations between the latent variables are displayed, estimated by structural equations modeling; in the upper diagonal, the determination coefficients are presents (i.e., squared correlation); all correlations were statistically significant (i.e. p ≤ .05).

Moderated Mediation Model

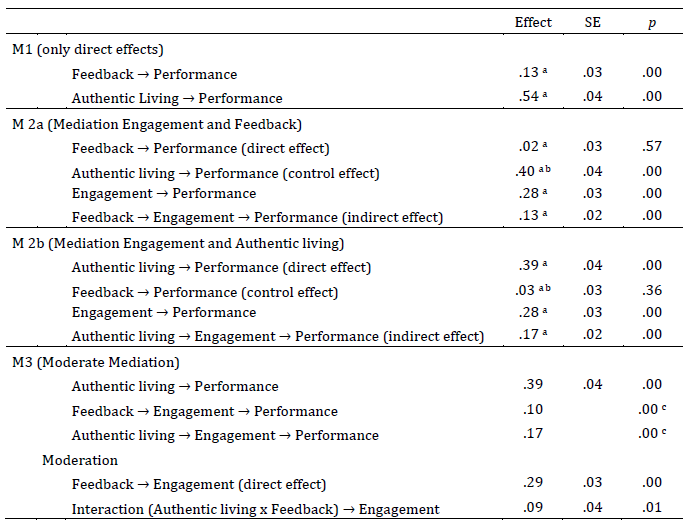

Results in Table 3 shows positive direct effects between performance and feedback, as well as between performance and authentic living. Furthermore, in model 2, the engagement fully mediated the relationship between performance and feedback; and engagement partially mediated the relationship between performance and authentic living. These results support the hypotheses from 2 to 6, and it partially supports hypotheses 7.

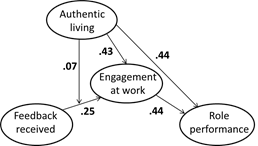

In model 3, we tested the moderation effect of authentic leaving on the relationship between of feedback and engagement, using a latent interaction variable. The moderation effect was positive and significative (b = .09; p = .01), which confirms hypothesis 8. It should be noted that the effects presented are not standardized and therefore cannot be mutually compared. To improve the interpretation of the effect sizes on the final model, the standardized parameters are presented in Figure 2 (the moderation effect was standardized based on the estimated variance of the interaction term and the engagement).

Table 3: Non-standardized parameters of moderated mediation modeling

Note: The variables described in the table were set as latent (the factor loadings of the item plots were omitted). a: parameters estimated using bootstrap (1000 resamples); b: direct effect between IV and DV used for mediation control; c = Statistical significance calculated by means of Sobel (for the final model, the parameters could not be estimated by means of bootstrap, as version 7.11 of Mplus has not implemented the bootstrap procedure in case of latent interaction in the model).

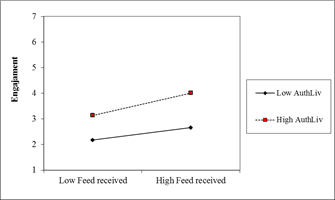

In Figure 3 we plot the interaction effects of the moderation model. Results show that, among individuals with high authentic living, the effects of feedback on work engagement are maximized; among individuals with low authentic living, however, the effect of feedback on engagement were flatter. These results contribute to the confirmation of hypothesis 9 in this study.

The indirect effect between feedback received and performance, mediated by engagement, depends on the level of authentic living. For the average level of living scores, the indirect effect was equal to .10 (SE = .01; β = .11); For the low and high levels of living, the indirect effects were equal to .07 (SE = .02; β = .08) and .13 (SE = .02; β = .14;), respectively. Indirect effects were statistically significant for all levels of authentic living (p <.05).

Discussion

In this study, the direct effects of feedback received and authentic living on work engagement were investigated, as well as the direct influence of engagement on role performance, and the indirect effects of feedback and authentic living on role performance, through the mediation of work engagement. Additionally, we sought to investigate the moderating role of authentic experience in the relationship between feedback and engagement.

Thus, first, the direct hypotheses between the constructs were tested and corroborated. The results obtained allowed for the confirmation of the effects of the feedback received on the engagement and role performance, valuing the important role of the social work context. This is because the feedback yielded by organizational members plays a role in the social interaction performed in today's companies, providing greater knowledge about individual performance in the workplace (Humphrey et al., 2007; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). In addition, the feedback received, as a job resource, has a potential motivation, contributing to the satisfaction of basic needs, which favors the engagement of individuals in their work activities and, consequently, greater efforts in the performance of their tasks (Ryan et al., 2021a, 2021b; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Leaders may also enrich followers’ job design may create work procedures through which employees provide help and feedback to each other (Bakker, 2022). In this sense, these findings contributed to the organizational literature when investigating a resource from the social context of work and its influence on positive behaviors and attitudes in the work environment (Pérez-Nebra et al., 2022).

Personal resources also have a potential for motivation by allowing the individuals to gain a sense of successful control over their environment, with optimistic and resilient characteristics for example (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b; Hobfoll et al., 2018; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Authentic experience, in this sense, has proved to be an important personal resource that positively influences both work engagement and role performance as, when individuals show to be more authentic, they tend to experience more positive states at work (Sutton, 2020; van den Bosch & Taris, 2013).

The research findings are in line with the assumptions of the JD-R Theory (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b), the Broaden-and-Build Theory (Fredrickson, 2001) and Social Cognition Theory (Bandura, 1991). While the former argues that the positive motivational state of engagement is responsible for a more favorable perception of work, which makes the individual strive for better quality performance (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), the second theory advocates the individuals' expansion of the repertoire of thoughts and actions, which makes them more proactive, therefore reflecting in a better performance (Corbeanu & Iliescu, 2023; Neuber et al., 2021; van Roekel et al., 2024), and the third theory advocates the idea that the individual is not merely a product of the environment; he takes control of his life through self-efficacy, goal setting and self-regulation, which makes him a self-organized, proactive and self-regulated person. Thus, it could be verified that the engagement exerted a positive influence on the performance of work roles.

The results of the newly reported direct influences contributed to a more robust analysis of the research model that involved complex relationships, such as mediation and moderation. In this sense, it was observed that engagement mediated the relationship between feedback received and role performance. According to the JD-R Theory, it is important to understand the psychological processes underlying the relationships between job characteristics and work outcomes (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b). It is through the motivational potential of certain job characteristics that certain outcomes are achieved through engagement at work (Corbeanu & Iliescu, 2023; Neuber et al., 2021). Thus, the job resources initiate a motivational process that drives the achievement of goals and development, leading to better results at work (Bakker, 2022; Lesener et al., 2020; van Veldhoven et al., 2020; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). It is in this sense that the feedback received contributed to the development and management of social relationships in the work context, which favored good performance and productivity, through work engagement, as Oldham and Hackman (2010) argue.

Engagement partially mediated the relationship between authentic living and performance. One possible explanation for the partial mediation is that the use of only the personal resource is not a sufficient argument for a mediation hypothesis involving engagement and organizational outcomes, since the model highlight the role of the context in the prediction of engagement and its consequences. In addition, research findings have discussed the reciprocal relationship between work resources and personal resources in predicting engagement and other organizational outcomes (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b). In this case, including only the personal resource for the engagement mediation model may have contributed little to the model. Finally, it is important to consider that other personal resources may have effects that differ from authentic living.

Although personal resources are integrated into the JD-R Theory in several ways, the moderating role of these characteristics has been studied, which the main focus is to increase the positive effects of work resources on engagement (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). The results of this research, in fact, have demonstrated that the interactive effect of work and personal resources on the relationship between feedback received and work engagement can be confirmed. In other words, the greatest effects of feedback on performance occur in individuals with high authentic living.

Conclusions

This study identified the moderating role of a personal resource in the relationships between the feedback received and the performance of roles, mediated by engagement at work. The research results showed that when individuals are more authentic, the information they receive about performance will strongly affect the motivation process at work. Engagement can subsequently contribute to positive outcomes in the work context, such as the responsibilities individuals assume in this environment.

This study tested more complex relationships among variables that have been empirically tested in other studies but not combined in their current form, using structural equations modeling and with the support of the JD-R Theory. For example, the moderating role of the personal resource demonstrated consistency with the model's new propositions, when considering a person x situation approach (Bakker et al., 2023a; Bakker et al., 2023b).

Future studies should include the work demands in the research model, as they are part of the JD-R Theory, mainly the challenging demands, which have been frequently related with engagement. In addition, studies should explore individual and contextual variables that have received little attention thus far, like in the case of core self-evaluations and psychological flexibility at work (personal resources), psychological safety and organizational climate (contextual resources) and career and development opportunities (job resources).

Nevertheless, the research came with some limitations. The use of self-reported research data collected at a single moment in time contributes to the common variance effects of the method. In addition, the causal direction presented in the study still needs further confirmation.

Therefore, contemporary companies could make efforts to enhance the work engagement, considering it is an important construct for individual and organizational development (Bakker et al., 2020; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2009). In addition, feedback increasing on the organizations is a way to enhance individuals’ knowledge on how they develop their activities. Another practice the companies could adopt is the creation of environments that facilitate authenticity, contributing to successful control in the work environment. Thus, the individuals’ actions can be coherent with their feelings and can contribute with positive individual (engagement) and organizational outcomes (role performance). On the other hand, work engagement should be a personal seeking, because the individual is being responsible for his/her development. Thus, situations deriving from organizations, in contact with personal characteristics, which individuals turn into positive actions, can produce better outcomes for individuals and for the organizations.

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI