Introduction

Election is a fundamental pillar in a democracy, and ensuring that such elections occur in a fair and honest manner is a significant challenge involving various factors, both political and institutional, such as a system that facilitates access to voting, secrecy, and fair competition with opposition inclusion (Dahl, 1975; Przeworski, 2000; Anderson et al., 2005). For a strong democracy, it is important to ensure a robust electoral process with clear laws that establish boundaries and possibilities, and that guarantee fair and secure competition from both institutional and social perspectives, thus ensuring transparency, security, and accessibility for its population (Norris, 2015). Part of this fits into the definition of electoral integrity, as defined by the Electoral Integrity Project, on which the research is based, conceptualized as: “international standards and global norms governing the appropriate conduct of elections” (ipsis litteris).

In Latin America in recent years, there have been protests by the population, and even challenges from competitors, especially from the losers, in elections, such as in Brazil in 2014, or suspicions of incumbent fraud in Bolivia in 2019. These events have raised questions about how the performance of elections can be impacted by the context and dynamics of political competition. Data gathered by the Global Corruption Barometer - Latin America & Caribbean by Transparency International1 in 2019 indicate that more than half of the people believe that the Presidentʼs office and members of parliament are the most corrupt groups. The same report shows that 1 in 4 people receive bribes in exchange for votes. In some countries, such as Mexico, this statistic is even higher, where 1 in 2 people claim to have received a bribe. The widespread mistrust regarding corruption in general can also affect electoral management.

Thus, the question that this study proposes to answer is: how do the characteristics of the Electoral Management Body (EMB) affect fraud? In addition to the difficulties of measuring corruption in elections, the literature (Lehoucq, 2003; Norris, 2014) indicates some points that are relevant to this attempt, such as identifying campaign financing fraudulently, vote-buying, political strategies to hinder opponentsʼ campaigns, media bias, and fake news.

According to Norris et al. (2013), not even consolidated democracies are immune to having contested elections, even if competitors accept the results. In the same study, the authors raise the question of how to determine if an election meets international standards and, based on evidence, identify which types of interventions contribute to improving elections. For example, in more specific situations such as the increase in voter intimidation and ballot fraud in sub-Saharan African countries (Collier & Vicente, 2012). The choice of Latin America for the analysis in this study is significant due to recent cases of contested results, as well as to identify how more specific cases behave and how to assess a region based on global standards.

One point to understand Latin America is to pay attention to the evolution of the region over the years and why some countries have managed to modernize to some extent while others have had greater difficulty dealing with social and political problems. In addition, the idea that the more developed a country is, the more democratic it will be does not necessarily apply to the region, as this relationship is not linear (Mainwaring & Pérez Liñan, 2003). Nevertheless, it is not possible to contextualize Latin America without considering the global perspective.

Even though elections are the cornerstone of democracy, where people have access to vote to choose who will lead and govern the country, this does not necessarily mean that the government will be responsive (Achen & Bartels, 2016). As Pzreworski (2019) emphasizes, representative institutions are in crisis, with some countries experiencing the rise of authoritarian, nationalist, and xenophobic leaders, such as Viktor Orbanʼs Hungary, Daniel Ortegaʼs Nicaragua, and Jair Bolsonaroʼs Brazil. He also argues that there is disillusionment among centrist voters, who are losing confidence in institutions.

Even in electoral processes where there is a high degree of acceptance, it is important to focus on aspects such as the quality of these elections, which are vulnerable to variations depending on the context in which they occur, even in situations with greater participation of actors and opposition (Norris, 2013; Edgell et al., 2018).

In Latin America, there are different levels of democracy and electoral integrity, which opens doors to explore how each country deals with the challenge of maintaining fair elections. One alternative to demonstrate that a country has the capacity to address this issue is for institutions to create mechanisms for society and organizations to closely observe the functioning of the process at various stages. Some organizations, such as the United Nations (UN), which in 2005 defined the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation, and the Organization of American States (OAS), play a role in sending international observers to monitor elections and produce technical reports on the management and occurrences.

The study considers, based on the Electoral Integrity Project (EIP), data2 from the most recent elections in Latin America included in the project (since 2021), analyzing all Latin American countries except Cuba. The work also utilizes data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem)3 in the analysis. This study aims to identify patterns and associations between the structure of electoral management bodies (referred to as EMB in this study), fraud (which includes various types of violations of electoral rules), and the participation of electoral observers (whether domestic or international). Methodologically, the study focuses on conducting exploratory and association tests through exploratory and descriptive statistical analysis.

1. Democracy and electoral integrity

According to Dahl (1971), equal consideration of citizensʼ preferences by the government is paramount. Thus, considering the voter as a structural agent of democracy is fundamental to the conventional understanding of democracy, as it is with the voters that it begins (Achen & Bartels, 2016). Therefore, the quality of democracy relies on certain assumptions, such as freedom of expression, alternative sources of information, the right to vote, free elections, etc. Other nuances are also considered to ensure a competitive and pluralistic scenario. Ideally, we should also consider how to frame fair elections in countries where opposition and parties are allowed and where, in the competitive process, more than one candidate participates in the electoral race (Hyde & Marinov, 2012).

One of the assumptions that encompasses the realm of electoral integrity is how the electorate and other actors involved in the process perceive the legitimacy of electoral administration and the extent to which responsible bodies are qualified to carry out electoral activities. Characteristics of these bodies ensure that there is democratic backing and that actions occur consensually, from the selection of members who are part of the electoral management body to the institutional design that governs electoral management and democratic elections as the final product of these policies. Beyond these points, there is also a need for acceptance of the electoral process by elites and civil society (Norris, 2014; Alvim, 2015). Some challenges are evident in ensuring electoral integrity, such as the political context of each country and region, which may vary and have particular aspects, the type of political regime, and electoral malpractice. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze electoral integrity based on normative definitions in measurement (Zavadskaya & Garnett, 2018).

When analyzing the quality of democracy and electoral integrity, it is essential to integrate concepts of vertical and horizontal accountability, as discussed by Shugart, Moreno and Crips (2003). Vertical accountability pertains to the connection between voters and legislators, ensuring mechanisms for elected representatives to align with the interests of their constituents. Conversely, weak vertical accountability can lead to a disconnection in this relationship, undermining democratic quality. Horizontal accountability, on the other hand, involves mechanisms through which different agencies and branches of government hold each other accountable. This is crucial for maintaining a balance of power and preventing abuses. The authors also argue that the design of electoral systems further impacts these dynamics, with mixed incentive systems enhancing responsiveness to local and national interests, while centralized systems can erode accountability.

Similarly, Levine and Molina (2011) argue that the quality of democracy should be assessed based on decision-making processes rather than the outcomes of these decisions. They emphasize that a high-quality democracy is characterized by free and fair elections, full citizen participation, and accountability, regardless of whether policies effectively address social issues such as inequality. This perspective underscores the importance of focusing on civil rights and democratic processes as central to assessing democratic quality (and electoral integrity), rather than conflating procedural integrity with broader social or economic outcomes.

There are several international agreements accepted on electoral integrity practices, which have increasingly led to the subject being treated with greater scientific rigor in academia, allowing for methods to operationalize and measure electoral integrity. This makes it possible to establish associations and comparisons in terms of levels of democracy, economy, and political systems, whether aggregated or not (Norris, Frank & Coma, 2013; Garnett, 2017).

The literature on electoral integrity argues that the institutional design of EMBs is a key factor in preventing fraud, particularly regarding the autonomy, technical capacity, and neutrality of these bodies. Norris (2015) emphasizes that institutional characteristics are closely tied to EMB performance, and based on this premise, analyzing how institutional design contributes to fraud prevention is essential. The theoretical expectation of this paper is that these arguments will also hold true in the context of Latin America.

1.1. Electoral Management Body and Observers

To ensure the credibility of elections, the democratic state needs to ensure that electoral governance complies with laws aimed at ensuring both institutional and social governance. Despite the complexity involved in defining electoral governance, it can be considered as a set of activities that involve creating and applying rules and adjudicating conflicts, these being the main tasks of electoral governance to deal with democratic elections (Mozaffar & Schedler, 2002).

Mozaffar & Schedler (2002) strengthen the literature by conceptualizing and adding to the analysis of electoral management three levels, namely regulation, administration, and adjudication. At the same time, the authors establish six dimensions of electoral governance: Independence (when the electoral management body is not tied to the government), Centralization (which concerns administrative location, whether it is centralized in a single district/state or occurs in different locations), Delegation (when electoral management is delegated to non-partisan actors), Specialization (when electoral governance may be the responsibility of two separate bodies, one administering and the other adjudicating), Regulation (regarding the nuances of elections that are directly indicated in legislation and/or the constitution), Bureaucratization (which refers to intra-organizational processes in each body and the ability to handle specialized administration processes in a professional and non-ad hoc manner).

In an analogy, electoral governance would be like a Matryoshka (“Russian doll”), with the largest layer, and the other layers inside being products generated through the formation process of electoral governance. In this process, the desired outputs are transparency, security, and compliance with rules according to international standards (Norris, 2013; Siachiwena & Saunders, 2021). A more recent perspective (James, Loeber, Garnett & Van Ham, 2016) on the functions of electoral management consists of: a) Organizing: organizing the electoral process from pre-election issues such as party registration, candidate registration, and voter registration, campaign regulation, and actual voting on election day, extending to the post-election process. b) Monitoring: monitoring electoral performance throughout the electoral process, such as campaigns and media, campaign financing, vote counting, thus ensuring good conduct and compliance with laws. c) Election certification: certifying election results in a legitimate and transparent manner, ensuring that those involved are aware of the procedure that generated the electoral results.

The academic literature explores the importance of electoral governance having independence, professional electoral agencies, and stronger electoral management bodies, as this set of mechanisms plays a fundamental role in ensuring fair elections in democratizing contexts (Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo, 2007). The literature review has interesting findings that contribute to understanding their functioning, models, and performance, as well as examining the variation in their autonomy, capacity, and competence around the world (James, Van Ham & Garnett, 2019). Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs) are entities that aim to lead and oversee some or all elements within the electoral jurisdiction for the direction of elections, with their main functions including deliberating on issues of voter and candidate eligibility, managing the voting process, vote counting, and affirming results (James, Van Ham & Garnett, 2019).

Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Venezuela, for example, share the same dimensions, with electoral justice separated from electoral administration, while electoral justice is linked to the judiciary. Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Peru, and the Dominican Republic share having electoral justice separated from electoral administration, with electoral justice external to the judiciary. On the contrary, Brazil and Paraguay have electoral justice responsible for electoral administration, while electoral justice is also part of the judiciary. The countries where electoral justice is responsible for electoral administration and electoral justice is external to the judiciary are Bolivia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and Uruguay (Otaola, 2017).

The autonomy of EMBs is directly related to their functions and whether they are subordinate to any specific government power. Despite ensuring the security and transparency of the process, it does not necessarily mean there is trust and legitimacy. Legitimacy is granted based on the trust that the actors involved place in the electoral process (Norris, 2015; Siachiwena & Sauders, 2021). Guillermo Rosas (2010) finds evidence that legislators have more positive evaluations of elections when they are organized by EMBs that are separate from the political process. This is because such EMBs do not face direct pressure from political elites, thus being more autonomous and instilling a higher level of confidence in the electoral process.

Beyond the stages of electoral governance described by Mozaffar & Schedler (2002), as outlined above, James et al. (2019) distinguish the organizational design of EMBs into seven dimensions:

1.Centralization: This concerns whether electoral management is centralized at the national level or operates through various agencies at subnational levels. This division can influence the efficiency of electoral management depending on its proximity to the electorate.

2.Independence: It addresses the degree of formal independence of EMBs from the government, including procedures for the selection, appointment, and removal of its members. The independence of EMBs can directly impact their ability to act impartially, affecting electoral integrity.

3.Capacity: It refers to the stability and resources of electoral management organizations to conduct elections, including resource allocation and utilization, such as technology, logistics, and personnel training.

4.Scope and division of tasks: This involves the range of elements of the electoral process for which the EMB is responsible, whether exclusively, shared with other institutions, or delegated to specific bodies.

5.Relationship with external actors: This addresses the interaction of EMBs with stakeholders interested in the electoral process, such as candidates, civil society, and international organizations, aiming to obtain feedback and increase transparency.

6.Technology: This pertains to the software and hardware used to organize and implement elections, including design, source code, vote recording, and databases.

7.Personnel: This concerns the individuals involved in election management, including EMB members and temporary staff, considering their specialization and ability to manage the electoral process.

These dimensions contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the organizational design of EMBs and their role in conducting fair and transparent elections.

Given these dimensions, James (2019) suggests a causal connection between the design of the EMB, the performance of the EMB, and the outcomes. The design encompasses the dimensions described above, which are directly linked to performance (quality of service, service effectiveness, cost efficiency, equity, impartiality, probity), and accountability, which is connected to outcomes (electoral integrity, citizensʼ trust in elections, political actorsʼ confidence in elections, and electoral legitimacy).

There are examples spanning over a century that help strengthen the argument of how global norms contribute to the spread of electoral integrity. Certain measures, such as the case of womenʼs suffrage, despite having begun a century ago, by the end of the first half of the 20th century extended to approximately 50 countries. Additionally, issues concerning electoral monitoring are significant, with important extracts from monitoring missions reporting on how certain problems affect the electoral process, such as vote-buying, media bias, tampering with vote counting, among others. These findings have strengthened an agenda on how these aspects influence institutions to prevent such occurrences and how civil society can have a more vigilant eye on electoral management (Norris, 2013). Building on the premise that standards of electoral integrity are increasingly widespread, one hypothesis explored in the literature is that malpractices are related to the weakening of electoral administration, distorting the means of electoral competition and thereby undermining public confidence in the electoral process, leading to increased abstention and even regime instability (Birch, 2013).

1.2. Electoral frauds

Why does electoral fraud exist and how can we deal with it? To answer these questions, we would need to mobilize a range of experts and consult what the social sciences have been producing for decades, and even then, we would encounter numerous problems. There are hundreds of ways to defraud an election, and obviously, I do not dare to try to catalog them in this space, moreover, this paper does not have this objective.

However, it is important to highlight that for some years political science has made efforts to conceptualize, map, and measure electoral fraud. Nevertheless, the challenge of the intricacies of empirically measuring fraud faces several epistemological and methodological debates, as well as how to deal with causal nature. The study of the theme spans generations in political science, but it has grown as the field has already been heavily influenced by behavioral and economic paradigms, such as formal models (Poteete, Jansson & Ostrom, 2010).

To avoid any confusion in definition, it is important to separate electoral fraud from corruption and malpractice. For example, Lehoucq (2003) defines electoral fraud as “clandestine efforts to shape the results of elections,” and for López-Pintor (2011), electoral fraud is “any deliberate action taken to tamper with electoral activities and materials related to elections in order to affect the outcome of an election, which may interfere with or thwart the will of the voters.” Electoral fraud would materialize, for example, in the tampering of ballot boxes. (Lehoucq, 2003; Birch, 2011).If for any reason the EMBʼs autonomy is compromised, society, the judiciary, and also the media, play a crucial role in monitoring elections by exposing malpractices. This collective effort contributes to ensuring electoral integrity in cases where there is a lack of accountability on the part of the government (Schedler, 2008; Birch & Van Ham, 2017). However, this is just one of the ways to address malpractice in electoral management, but it is important to compensate for the potential vulnerability of the electoral management body to political pressures (Norris, 2015).

Although electoral fraud has been associated with authoritarian regimes over the years, malpractices are growing in democracies in recent years, reinforcing the need for actors such as international observers to closely monitor the electoral process (Birch, 2011; Donno, 2013). The effects of electoral fraud can be very serious, leading to political instability and violent protests, which provide ample opportunities for actors with an interest in subverting the process, often autocrats (Cheeseman, 2018). Vickery and Shein (2012) emphasize that the combination of fraud with malpractices opens the door to a third definition: criminal malpractices, which involve gross and intentional negligence.

In an attempt to contain and identify fraud, some alternative efforts involve the involvement of multiple actors to ensure a transparent process. Electoral observers contribute to these exercises, as well as technologies that enable researchers to use machine learning to estimate models and analyze electoral data and results, and to identify fake news and its proliferation (Cantú & Saiegh, 2017; Chaudhary et al., 2022). Election technologies also contribute to another stage of the electoral process, which is the auditing of results. The audit is an investigation that takes place in the post-election period, a standard procedure aimed at addressing any allegations of fraud that may have occurred during the elections, including claims of computational issues and source code problems in the case of electronic voting machines and widespread malpractices.

In exploring how the institutional design of Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs) influences electoral fraud, this research addresses a crucial gap in the literature. While substantial research has examined the role of EMB autonomy, capacity, and responsibilities in relation to electoral integrity, there is limited understanding of how these factors specifically impact electoral outcomes in different regional contexts, particularly in Latin America. This research aims to bridge this gap by investigating the relationship between EMB characteristics and the prevalence of electoral irregularities, such as fraud and malpractices. By focusing on Latin American elections and considering the role of electoral observers, the study offers valuable insights into how these elements interact and contribute to enhancing electoral systems and adherence to global standards of fairness. This examination is essential for advancing our understanding of how to improve electoral management and ensure more credible and legitimate elections.

2. Data and methods

How do the characteristics of Electoral Management Bodies affect electoral fraud? In this section, I present the techniques I use to answer this question and discuss the methodological procedures. The description and exploration focus on the relationship between electoral bodies, international observers, and electoral fraud, as presented in the previous sections. The research strategy examines the Electoral Integrity Project (EIP) database, with the inclusion of observers - both international and domestic - integrated into the main analysis to assess their isolated effects on electoral fraud. Data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) are also utilized in the analysis and explanation. The study has a sample size of 39 cases, which includes all countries in Latin America except for Cuba.

The study will employ Pearson correlation techniques to test if the variables vary together; t-test to compare samples of observer presence in elections; and exploratory analysis, aiming to identify patterns in the proposed relationship. I selected the variables for this study in accordance with the theoretical assumptions of the literature.

2.1. Data analysis and strategy

To empirically test the relationship between the variables, the study initially employed Pearson correlation tests to identify associations and variance among the variables under consideration, with elections as the main unit of analysis. The studyʼs scope aligns with the data from the Electoral Integrity Project, which begins from the year 2012. Therefore, following this logic, the research adopts this timeframe even in analyses involving other databases such as V-Dem.

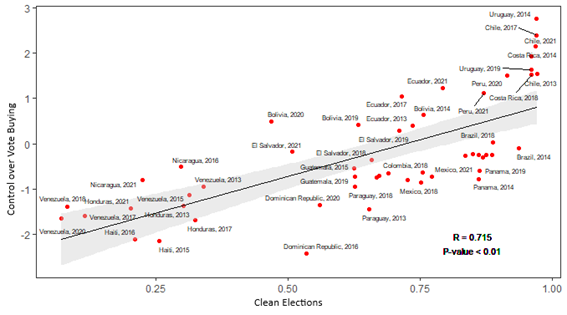

Figure 1 displays a strong and positive correlation between the vote-buying index and the clean elections indicator, with a robust coefficient of 0.715 and a significance level of P-Value < 0.01. Among the elections analyzed, the highest scoring in both indicators is the 2014 election in Uruguay, while the lowest scoring is the 2020 election in Venezuela.

Figure 1: Source: Developed by the author based on V-Dem data Correlation between Clean Elections and Vote-buying

The elections in both poles took place in South American countries. In 2014, Uruguay was experiencing a context of prosperity and stability in economic and democratic terms under President José Mujica, accompanied by a period of regional growth in the preceding years, particularly in Brazil and Argentina. Venezuela also appears with low scores in the years 2017, 2018, and 2015. The year 2013 is the furthest in terms of time and also from the negative scores, suggesting a degradation of electoral governance in the country in recent years.

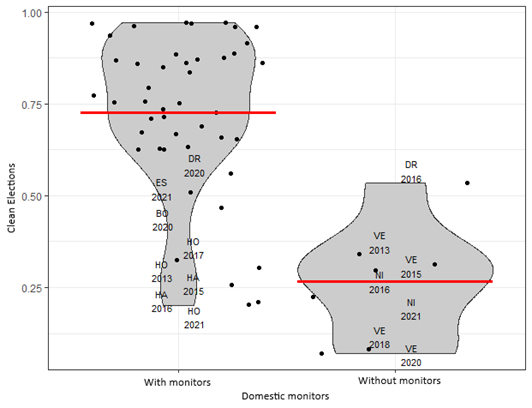

Figure 2 depicts the t-test used to assess the difference in mean scores between elections in countries that did not have restrictions on domestic monitors and countries that restricted the participation of domestic monitors using the variable of domestic monitors in relation to clean and fair elections. The mean score for countries that did not have restrictions on monitors in their elections was 0.725, while the mean score for countries that restricted monitors was 0.266. Countries that allowed monitor participation showed a significant difference in clean election scores, with a mean difference between samples of 0.459 and a P-value < 0.01, and a t-value of 6.714.

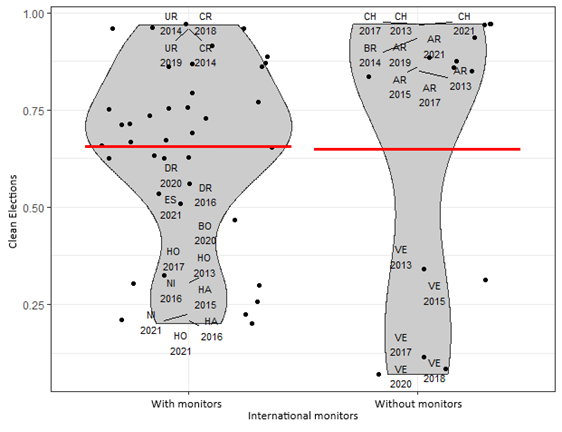

The t-test with the variable of international monitors follows a slightly different logic as the operationalization deals with the presence of monitors rather than restrictions. The test result indicates a mean of 0.655 for countries that had the presence of monitors and 0.648 for countries that did not.

Figure 2: Source: Developed by the author based on data from V-Dem T-Test of clean elections and domestic monitors variables

It is possible to visualize in Figure 3 the t-test with international monitors, with a difference that was much smaller than the result with domestic monitors, as described above. In this sense, it is possible to observe that elections with restrictions on monitors did not obtain a good score on the indicator of clean elections, highlighting Venezuela and Nicaragua. Some countries, even with monitors, had low scores, as in the case of Honduras and Haiti. It is worth noting that even countries with a low degree of democracy still accept and authorize monitors, and autocratic countries like Venezuela and Nicaragua reinforce the deterioration of their democracy by not authorizing them (V-Dem, 2022). In the case of the sample without monitors, countries like Chile and Argentina raise the average, but even so, it is possible to observe countries like Venezuela, where there was no presence of international monitors and also scored low on the clean elections indicator.

Figure 3 Source: Developed by the author based on data from V-Dem T-test of the variables clean elections and international monitors

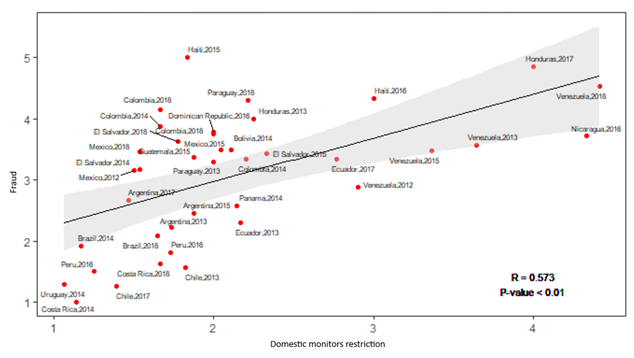

Internally, some organizations play the role of closely monitoring the election, especially non-governmental organizations, researchers, and the like. In Figure 4, it is possible to visually observe the correlation test between Domestic Observers Restriction and Frauds.

Figure 4 Source: Compiled by the author based on data from the EIP Correlation between Fraud and Domestic Observers Restriction

The statistical result indicates a moderate positive correlation of 0.573 with significance p-value < 0.01. This result shows how to some extent the participation of domestic monitors is related, in most cases, in Latin America with less fraud. This type of relationship is difficult to interpret due to the nature of electoral observation: in countries with lower electoral integrity, there is more motivation for domestic actors to want to observe, but at the same time, there may also be more intimidation and repression against mission members. However, an interesting piece of information that this correlation conveys is the receptivity of the countryʼs electoral management system to domestic observers. Donno (2013) discusses how international observers are positively connected with higher levels of democracy and electoral integrity. Her argument goes in the direction that this positive relationship contributes to the reduction of potential fraud and malpractice.

In addition to domestic observers, most countries in the region participate in international cooperation organizations for electoral observation. Thus, during elections, the UN, European Union, OAS, among others, send technicians, researchers, and trained professionals to observe the electoral process, analyzing whether the elections followed international standards of fairness. This is also a way for the receiving country to demonstrate that its electoral institutions are playing a responsible role in ensuring electoral integrity. Figure 5 shows the correlation graph between the variable of International Observers Restrictions and Fraud.

Figure 5. Source: Developed by the author using EIP data Correlation between Fraud and International Observers Restrictions

The result of this test shows that the correlation is weaker, reaching a coefficient of 0.472 with significance of P-value < 0.01, which is statistically considered a moderate positive relationship. Similar to the case of the relationship with domestic monitors, it is possible to notice some countries that had greater openness to the participation of international observers and others that are more restrictive, but overall, there is greater acceptance than restriction of international observers.

There is a significant concentration regarding countries in the region allowing international observers, where the perception of fraud scores between 3 and 4 in 17 out of the 39 elections. Once again, at the extremes, Costa Rica stands out, showing higher participation of international monitors and the lowest perception of fraud. On the other end, some cases are noteworthy: Venezuela has low participation of international monitors in all analyzed elections (2012, 2013, 2016, and 2018) and a temporal decline correlated with a high value in the fraud indicator. The elections in Haiti in 2015 showed a high score of fraud in the electoral process, and in contrast to other cases with this pattern, Haiti in 2015 had high participation of international observers. The case of Haiti in this sample is an outlier, as explained earlier, due to the political context.

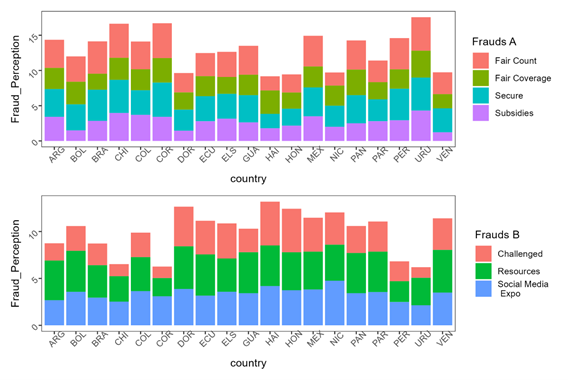

In the analyzed sample, the case that most closely resembles Haiti in 2015 is Paraguay in 2018. Despite receiving numerous domestic and international observers, there were some allegations of fraud and legal insecurity that undermined the integrity of the electoral process. Given the correlation tests, in the following Figure 6, it is possible to observe the distribution of variables from the fraud block by country, thus enabling the visualization of the incidence of each variable individually.

Figure 6 Source: Compiled by the author from EIP data Distribution of dependent variables by country

To better understand the graph and avoid potential misinterpretations, I describe below how the selected variables are operationalized according to the description of the results and divided into two parts in the figure, with variables Frauds A indicating higher scores mean higher integrity, and variables Frauds B indicating higher scores mean lower integrity.

In the 2010s, Haiti, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic were the countries where there was the most contestation of results by candidates and parties (challenged), respectively with an index of 4.66, 4.62, and 4.22, which could be indicative of abuse of power by the government. Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Chile are the countries with the lowest scores in terms of contestation (1.12, 1.22, and 1.28), indicating that in these countries there is a greater acceptance by the losers in the election.

It is interesting to note that Honduras and Haiti do not show a discrepancy when analyzing the variable “resources” which indicates the improper use of state resources for campaigning, despite still having a considerably high score (Honduras = 4.05 and Haiti = 4.33). Considering that a higher score denotes worse integrity, Venezuela leads with 4.55, along with the Dominican Republic with the same score, indicating that these are the countries where there is the strongest indication of misuse of resources.

Nicaragua appears with 4.75, one of the countries with the highest score when it comes to the media exposing any type of fraud (social media expo). This may indicate that regardless of the occurrence of other frauds, the country's press has enough freedom to at least report any suspicion of fraud that occurs during elections. Along with media reports, the contestation of results by candidates and parties is also high. Other countries where experts claim that the media exposed fraud in the last elections were Haiti with 4.18 and the Dominican Republic with 3.87. The countries that dealt least with this type of situation were Uruguay and Chile, scoring low in this variable (2.14 and 2.49 respectively).

It is important to connect the relationship between the media exposing suspicions of fraud and the media providing fair coverage of elections, considering that in these countries there is alternative media as well as state-owned media. The fair coverage variable measures how fair the mediaʼs coverage was, operationalized on a scale where the higher the score, the fairer the coverage. Uruguay remains ahead with 3.81, while Chile, which previously appeared alongside Uruguay, now ranks sixth among the sample countries. The country ranking second is Panama with an indication of fair election coverage at 3.62. Haiti, which typically scores negatively in terms of fraud and electoral integrity variables, now ranks fourth with a score of 3.31. This means that as coverage becomes fairer, the exposure of suspicions of fraud follows suit, which is not the case for the Dominican Republic, which has the second-highest exposure to fraud and a score of 2.44 in the fair coverage variable.

Beyond the media, ensuring that electoral institutions fulfill their role in guaranteeing fair elections and competent administration is essential, and one of the indicators involving this set of issues related to electoral governance is how the vote count occurs. The fair count variable measures how fair the vote count was in the elections. Costa Rica ranks first with a considerably high score (4.94), followed by Chile (4.83), Uruguay (4.75), and Brazil (4.59). It is interesting to note that in these four countries, the institutional design of electoral governance functions somewhat differently. While Uruguay has the Electoral Justice responsible for administering elections and is also independent from the judiciary, in addition, members of the Electoral Court (EMB) are selected only by the legislature.

In Chile, the institutional design operates in the opposite way; that is, electoral justice is not linked to electoral administration but is part of the judiciary, and members of the Electoral Service (EMB) are selected by both members of the legislature and the executive. One characteristic that is repeated among these countries is that political parties have a role in the management bodyʼs process, but in Chile, it is indirect, and in Uruguay, it is partially direct (Otaola, 2017). The country leading this indicator, Costa Rica, has similar characteristics to Uruguay in terms of electoral governance, with electoral justice independent of the judiciary and responsible for electoral administration. However, members of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, the electoral management body, are selected by the judiciary, and parties do not participate in the process.

In this section, I will analyze the variable “secure,” which indicates whether electronic voting machines were secure, as another important component serving as an indicator of electoral integrity and as an alert for possible fraud. The countries with the highest index of contested elections are repeated, in the same order, in the “secure” variable: Haiti (2.04), Honduras (2.41), and the Dominican Republic (3.00) had the lowest scores, followed by Nicaragua (also with 3.00). In terms of security, the countries that obtained the highest scores were repeated in relation to election contestation, but in a different order. In the ‘secure’ variable, Costa Rica had the highest score with 4.87 followed by Chile (4.71) and Uruguay (4.68).

Finally, one of the variables that indicates whether there is a fair process by the electoral administration is how resources are distributed. The “subsidies” variable indicates how resources were divided equitably. A higher score indicates greater integrity. In this variable, the scores were considerably low, with Uruguay (4.30) ranking first, followed by Chile (3.96) and Colombia (3.96).

Including Uruguay, Chile, and Colombia, only 7 out of the 19 countries in the region scored above 3.0: Mexico (3.49), Argentina (3.41), Costa Rica (3.41), and El Salvador (3.14). The other 12 countries scored from 2.92 (Peru's score) downwards. The worst performers, indicating poor distribution of resources in elections, were Venezuela (1.22), followed by the Dominican Republic (1.44) and Bolivia (1.50).

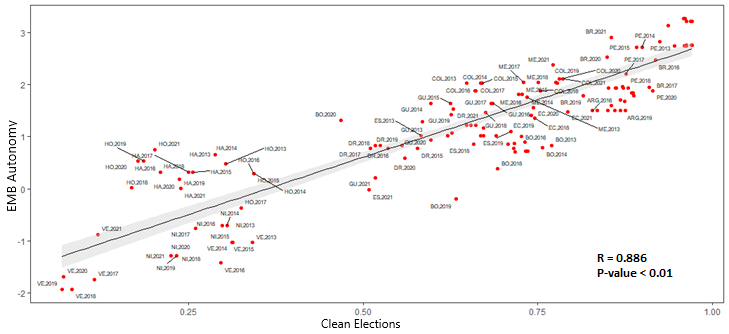

It is noteworthy that in the region, there is a positive correlation of 0.886 between the autonomy of the electoral management body and clean elections, as can be seen in Figure 7, with Costa Rica showing a positive performance at one extreme, and Venezuela having the worst performance in the region in recent years. The correlation had a p-value < 0.01.

Conclusions

The study aimed to reflect on how the institutional design of Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs) and their responsibilities, autonomy, capacity, and attributions may relate to electoral irregularities such as malpractices, fraud, and others, following an international research agenda that explores how the distribution of these variables is related to electoral integrity and the willingness of governments to adhere to global norms of electoral fairness, as well as how the participation of observers relates to different variables of electoral integrity and the institutional design of EMBs.

The research results support Norrisʼ hypothesis (2015) that institutional characteristics matter for performance in terms of electoral integrity, at least in the cases of Latin America. In this region, these characteristics include autonomy from governments and the capacity of EMBs.

The descriptive findings of the research in Latin America strengthen some arguments and hypotheses raised by literature focused on other regions, such as the hypothesis that international actors relate positively to democracy and electoral integrity, thereby reducing the scope for possible fraud or malpractices (Donno, 2013), and the hypothesis about a causal connection between the institutional design of electoral management bodies, EMB performance, and the outcomes of more integral elections that contribute to the legitimacy of elections (James et al., 2019). However, it is important to note that while the presence of domestic observers is often discussed in terms of its impact on electoral integrity, it is not accurate to assert that countries with no domestic observers are actively restricting their presence. This assertion oversimplifies the complex factors influencing observer presence and electoral dynamics. However, it can be affirmed that the presence of observers has a generally positive impact on electoral integrity.