1. Introduction

Epigenetic mechanisms are major regulatory processes involved in the control of plant development and their responses and adaptation to the environment1. Epigenetics, which does not rely on changes in the DNA sequence, has been associated with stably inherited phenotypic variations. Of course, epigenetic processes are important actors in the memory of plants and, as such, may provide innovative ways to face the threat that climate changes and associated stresses impose on the grapevine. Plant epigenetic memories are likely to play major roles in processes such as acclimation and/or adaptation of grapevine plants to stresses by generating favorable epigenetic alleles, also called epialleles (reviewed in Berger and others2).

In this short article, we briefly review the current knowledge of epigenetic regulation in grapevines and discuss how epigenetic regulations and memories could provide additional ways to face the constraints that climate changes impose on viticulture in Uruguay. Such mechanisms could be of primary importance in plants that, like grapevines, are clonally propagated and, therefore, present limited genetic diversity.

2. Epigenetic mechanisms in plants: a short summary

One of the most important and well-described epigenetic marks is the methylation of the genomic DNA, which was thought to occur only on the 5th carbon of cytosine (5mC)3 until the recent discovery that methylation can also take place on the 6th carbon of adenine (6mA)4. Epigenetic processes also involve histone post-translational modifications (HPTMs), histone variants and enzymes involved in chromatin remodeling5. In plants, DNA methylation at cytosine can occur in all sequence contexts: CG and CHG (H=C, T or A), which are symmetrical sites because methylation occurs on both strands. It also occurs at the CHH sequence context, which is non-symmetrical, as only one strand is methylated. DNA methylation can be established at C, in any sequence contexts, during development or in response to environmental signals, by a mechanism called the RdDM pathway (RNA directed DNA methylation). The RdDM pathway involves the Domain Rearranged Methyltransferases 1, 2 (DRM1/2), DRD1 and 24nt-long small RNAs. In addition, the chromomethylase 2 (CMT2) associated with the helicase decrease in DNA Methylation (DDM1) will establish DNA methylation at CHH to be located in heterochromatic regions 3)(6) .

During DNA replication, the newly produced DNA strand is not methylated, generating hemimethylated DNA molecules at the symmetrical sequences CG and CHG. In both cases, specific enzymes will re-establish methylation at hemimethylated sites. In the CG context, MET1 associated with Variant in Methylation 1 (VIM1), 2 and 3 will add the methyl on the newly incorporated cytosine. The CHG methylation maintenance depends on plant specific enzymes, called the chromomethylases (CMT), mainly CMT3. Finally, at CHH sequences, methylation of the newly synthesized DNA strands relies on the RNA directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway. However, as for de novo methylation, CMT2 also participates to maintain methylation in heterochromatic regions. Both CMTs are characterized by a chromo domain that allows their recruitment at the methylated histones H3K9 me2 (for a complete review of DNA methylation3). Methylated cytosine can be removed by DNA demethylases (DMT) in an active process, or passively diluted following replication when the maintenance methylation is not working after cell division7.

Additional epigenetic marks include histone-post translational modifications (HPTMs), which occur at various amino acids located essentially, but not exclusively, on histone H3 tail. They include lysine, threonine and serine residues. The main HPTMs are acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation. In addition, histone variants can impact on the nucleosome composition, which, together with HPTMs, affect chromatin structure. HPTMs, DNA methylation as well as histone variants and additional factors such as chromatine remodelers will determine the transcriptionally active or inactive state of chromatin5.

3. What do we know about epigenetic regulations in grapevine?

Even though epigenetic regulations remain poorly investigated in grapevine (Table 1), there is an increasing number of studies on the role of epigenetic processes in grapevine (for recent reviews and references therein2)(8)(9) . They include the recent description of the grapevine leaf methylome, which has shown that this plant shares common characteristics with other clonally propagated plants, specifically low methylation levels in the CHH context10. Similarly, the fruit methylation landscape was recently described; however, it did not provide evidence of major changes in levels or distribution of methylated cytosine during fruit ripening, and no clear function could be attributed to this epigenetic mechanism in grape berries11, which differs from what was demonstrated in tomato, strawberry or orange fruits12. In contrast, it has been suggested that in grape berries, as in many other fruits, the repressive mark H3K27me3 seems to play a more prominent role than DNA methylation in controlling fruit ripening, by regulating the expression of genes encoding key transcription factors13.

Indeed, epigenetic regulations seem to be involved in many other processes in grapevine, as in many other plants; they contribute to grapevine phenotypic plasticity and to its clonal diversity14. The analysis of methylation in Malbec clones grown in different environmental conditions suggested that the difference in phenotype between clones could not be explained by genetic differences, suggesting that epigenetic variations might play a key role in grapevine phenotypic plasticity. The demonstration of a direct involvement of DNA methylation in defining grapevine phenotypes is however still lacking. In addition, many possible roles of epigenetic regulation and memory have not yet been investigated in this plant. These include studies focusing on the memory of abiotic stresses, which are still very limited in this plant15, as is the study of the impact of the parent on the epigenomes and phenotypes of the clonally propagated progeny. For example, what is the relative contribution of the plant environment and of the parental origin to the methylation landscape of a plant in a specific vineyard16. Additionally, grapevine is a grafted plant, and there is accumulating evidence of an epigenetic dialogue between the two graft partners that may lead to epigenome remodeling of both the rootstock and the scion17.

Table 1: Summarized references of different mechanisms of epigenetics in plants (in green) and those related to the epigenetic contribution to memory in plants (in blue)

| Mechanism of epigenetic | Plant species | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic mechanisms in plants | ||

| Concept of epigenetic | Arabidopsis | Pikaard and others1 |

| Concept of epialleles | Grapevines | Berger and others2 |

| Methylation of DNA occurs on the 5th carbon of cytosine (5mC) and on the 6th carbon of adenine (6mA) | Arabidopsis | Zhang and others3 Boulias and Greer4 |

| Epigenetic marks: histone post-translational modifications, histone variants and enzymes involved in chromatin remodeling | Not specified | Lauria and Rossi5 |

| RNA directed DNA methylation and its location | Arabidopsis | Zhang and others3 Zhemach and others6 |

| Epigenetic marks: Methylated cytosine can be removed by DNA demethylases (DMT) | Arabidopsis and other 13 species | Liu and others7 |

| Epigenetic regulation | Grapevines | Berger and others2 Fortes and Gallusci8 |

| Low methylation levels in the CHH context (in leaves) | Grapevines and other 33 angiosperm species | Niederhuth and others10 |

| No major changes in methylated cytosine (in fruits during ripening) | Grapevines | Shangguan and others11 |

| DNA methylation is not a major ripening regulator (fruits) | Tomato, strawberries and sweet orange | Tang and others12 |

| Mark H3K27me3 for DNA methylation (fruits) | Grapevines | Lu and others13 |

| Epigenetic as a clonal diversity | Grapevines | Varela and others14 |

| Memories of abiotic stresses; DNA methylation patterns of grapevine clones are more dependent on clonal origin than location | Grapevines | Marfil and others15 |

| Leaf DNA methylation landscape is determined both by the plant environment and by their parental origin | Grapevines | Xie and others16 |

| Epigenom modeling between scion and rootstock | Grapevines | Rubio and others17 |

| Epigenetic contribution to the memory in plants | ||

| Epigenetic mechanisms as a process of memorizing in plants | Arabidopsis and others | Crips and others18 |

| Stress-induced epigenetic changes can be transmitted to the next generation | Plants and animals | Anastasiadi and others19 |

| Plants may maintain their epigenetic landscape over the years, although environmental conditions may generate an epigenetic drift | Grapevines | Gallusci and others21 |

| Priming as a somatic memory | Corn, Poplar | Mozgova and others22 |

| Priming is partly mediated by memory genes, the transcriptional state of which is determined and maintained by epigenetic processes | Arabidopsis | Baurle23 |

| Priming as acclimation to stress | Grapevines | Delaunois and others24 |

| Epigenetic marks are mediated through mitosis in the stem cells located in meristems | Grapevines | Latzel and others25 |

| Regenerated plants maintain part of the epigenetic imprints of the organ of origin | Grapevines | Wibowo and others26 |

3.1 Epigenetic contribution to the memory of plants

By definition, epigenetic regulation is part of the mechanisms that determine the memory of plants. Of course, several other processes have also been associated with the ability of plants to memorize and re-use the information they receive from endogenous or external signals, such as the accumulation of metabolites, hormones, the post-translational modifications of proteins, including transcription factors and other regulatory proteins, and, more recently, epigenetic mechanisms18. The latter may play a major role in the context of climate change as they embody important aspects of the memory of cells1. Epigenetic marks are maintained during mitosis, which allows a somatic memory of epigenetic changes, whether they are developmentally determined or generated by environmental signals including stresses. A clear example of somatic memory induced by an environmental signal is provided by the study of vernalization in Arabidopsis18. Furthermore, part of the stress-induced epigenetic changes can be transmitted to the next generation, a process that, however, depends on the type of reproduction19.

Intergenerational (1 generation) and transgenerational (more than 1 generation) epigenetic inheritance is still poorly understood, and require the maintenance of epigenetic information through a complex series of events including meiosis, gametophyte development, fertilization and the subsequent embryo development20. These different steps are characterized by epigenetic resetting and remodeling, limiting the eventual transmission of stress induced epigenetic information to the next generation. Transmission of epigenetic marks to the next generation is more likely to occur in the case of non-sexual propagation as there is neither meiosis nor fecundation, although for apomictic development the Macrosprore Mother Cell follows a modified sexual cycle. In non-sexual propagation, new plants are generated from meristems of the mother plant and may, therefore, retain part of the parental epigenetic imprints. Evidence of such an inheritance has been suggested both in poplar and strawberry18. Finally, in grapevine, as in other perennials, plants may maintain their epigenetic landscape over the years, although environmental conditions may generate an epigenetic drift21. Such a transannual memory, transmitted through epigenetic information stored in the meristem, was shown in poplar after drought stress. The importance of such a transannual memory in determining the progressive adaptation of plants to their environment remains so far poorly understood20.

3.2 Epigenetic aspects of plant priming: applications to grapevine

Several works have demonstrated that DNA methylation remodeling, changes in the distribution and quality of histone posttranslational modifications (HPTMs) and histone variants are essential to the plant responses to different abiotic and biotic stresses21. Plant stress somatic memory contributes to their acclimation to the environment, a process also called priming. Priming consists on the response of a plant to a first stress (biotic or abiotic) that will be, in part, memorized. This molecular memory will be maintained during a recovery period and mobilized when the plant faces subsequent stresses22. In that sense, the plant is prepared to better respond to additional stresses. At the molecular level, priming is partly mediated by memory genes, the transcriptional state of which is determined and maintained by epigenetic processes23. As far as grapevine is concerned, priming has been described in many different situations to acclimate plants to biotic or abiotic stresses24. However, there is little analysis of the molecular responses and the epigenetic determinants of priming. Studies evaluating the grapevine plant responses and memories using appropriate molecular approaches are therefore now necessary.

3.3 Trans- and/or intergenerational plant epigenetic memories: grapevine specificities

Works in Arabidopsis have shown the stable transmission of epigenetic marks over generations after sexual reproduction. This is established for intergenerational (one-generation) transmission of epigenetic information but is still unclear for the transgenerational (several generations) inheritance of epigenetic information generated by stress (reviewed in Gallusci and others21).

In clonally propagated plants such as grapevine, the progeny is generated by cutting. In this case, the maintenance of epigenetic marks is mediated through mitosis in the stem cells located in meristems25. Of course, generating cuttings may lead to re-juvenilization and resetting of some of the epigenetic imprints of the parental lines. However, recent work has shown that even when going through plant regeneration, which corresponds to a major developmental reprogramming, the regenerated plant maintains part of the epigenetic imprints of the organ of origin26.

As far as grapevine is concerned, there is little investigation on how the growing conditions of mother plants affect the phenotypes and epigenomes of progenies generated by cuttings. However, in a broad sense, the grapevine plant environment seems to be an important determinant of the plant methylome16. This suggests that epigenetic imprints, carried over from the parental plants, may be transient in time or erased by the progeny's new growing conditions. In contrast, other works indicate that the DNA methylation patterns of grapevine clones are more dependent on clonal origin than location15, rather consistent with a long standing epigenetic parental memory.

Studies are needed to focus on the transgenerational priming of clonally propagated plants as a new strategy for grapevine adaptation to climate change, as discussed by Tan & Rodríguez López27. As mentioned by the authors, viticulture could benefit from a deeper understanding of how this epigenetic memory of stress is established, maintained, and eventually reset, leading to the production of more resilient grape varieties.

4. Epigenetics as a new lever for grapevine adaptation to climate change in Uruguay

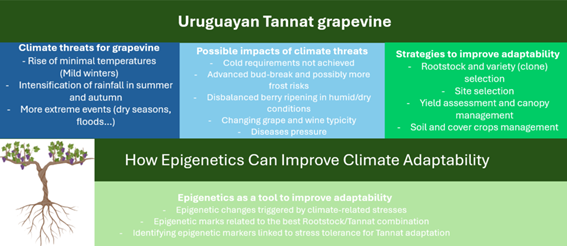

The relationship of grapevine with climate has been more thoroughly studied in the world than other perennial crops because the developmental characteristics of the plant are strongly associated with the characteristics of the wine, in close relation to the local climate. In Uruguay, for example, Tannat, known for its distinctive wines, is considered the emblematic red variety due to its adaptation to local conditions 28)(29) . However, climate change poses significant challenges to grapevines and the quality of wine worldwide30, including Uruguay.

The latest IPCC report31 highlights the expected changes, including higher temperatures, increased extreme heat events, and reduced cold spells. Warm nights are projected to increase even more than warm days. It is expected that a rise of minimal temperature (between 2 ºC and 4 ºC for the end of the century) may happen during the winter season in the next decades, while rainfall is predicted to intensify during summer and autumn, potentially leading to more floods.

Understanding and adapting to these climate variations is crucial for viticulture in Uruguay32. A rise of minimal temperatures during winter could alter chilling accumulation, impacting on budding development and yield components. Varieties with high requirements of cold during the dormancy may no longer be adapted in the near future. Mild winters also can advance bud break and other phenological phases, implying an increase in frost risks. Grapevines could have an epigenetic response during chilling stress, as reported by Sun and others20 in Muscat Hamburg cv, and Zhu and others33 in other non Vitis vinifera vine species (Vitis amurensis). At the same time, an increase of precipitations during summer could impact the interaction between grapevine and fungi diseases. High amounts of rainfall during grape ripening (summer and beginning of autumn) could impact grape quality (and its oenological potential) when high sanitary pressure occurs. The increase of climate extreme events like droughts (more frequent and severe) also impacts yields and grape quality, as we saw in the last harvests (see Fourment and Piccardo34). There is vineyard management that could help to a better adaptation to these climate threats, like vineyard installation zoning, rootstock and varieties selection, yield assessment, soil and cover crops management and even irrigation 32)) .

Furthermore, in addition to vineyard management methods, which allow alleviating some of the threats climate poses to vine production, plant breeding may also lead to the generation of new varieties better adapted to the environment. A recent publication35 discusses adaptation strategies made by winegrowers in Uruguay. However, no molecular tools are envisaged for that purpose. The public acceptability of Tannat as our flagship variety questions the use of breeding approaches to adapt this variety in the context of a changing climate as well as the use of other varieties that could be more adapted to future climate scenarios.

Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, play a role in grapevine stress responses. Examining the epigenetic changes triggered by climate-related stresses, such as drought and temperature fluctuations, can provide insights into grapevine adaptive strategies. This knowledge can guide the selection and breeding of grapevine varieties better equipped to cope with changing environmental conditions. Tannat, with its favorable agronomic behavior and oenological potential, stands as an example of a well-adapted cultivar in Uruguay, showcasing the importance of understanding the epigenetic basis of adaptation. Varela and others14 suggest that grapevine epigenome might contribute to the vineyard terroir. In that sense, we wonder how the epigenome of Tannat, developed in different winegrowing regions of Uruguay, with contrasting climates and soils, and different growing conditions, might vary.

On the other hand, epigenetic variations contribute to phenotypic plasticity, enabling grapevines to exhibit diverse traits in response to environmental cues, as reported by Varela and others14 in Argentinian wine regions for Malbec cv. Studying the epigenetic basis of phenotypic plasticity in grapevines can help identify specific traits that promote resilience. This knowledge can be utilized for breeding strategies aimed to enhance the grapevine adaptability to climate change in Uruguay, e. g. by identifying combinations of varieties and rootstocks that show greater plasticity or identifying inter-clonal variability within Tannat cv. cultivated in different wine regions. By exploring and harnessing epigenetic variations, grapevine materials can be selected and managed more effectively to withstand changing climatic conditions.

Finally, epigenetics could be an efficient breeding strategy to consider (Figure 1). Epigenomic-wide association studies (EWAS) may provide valuable tools for determining what heritable epigenetic variations are associated with desirable grapevine traits2. Generating epigenetic diversity within Uruguay's climate may help identify epigenetic markers or signatures linked to stress tolerance and other crucial traits for Tannat adaptation. By utilizing these epigenetic breeding approaches, it becomes possible to enhance the resilience and adaptability of grapevines in Uruguay, contributing to the sustainability of viticulture in the face of climate change.

5. Final comments

There is an urgent need to develop innovative strategies to generate and use heritable epigenetic variations for crop improvement, without relying on genetic diversity and sexual reproduction and/or epigenetic memories to prime plants facing stresses. Such methods will undoubtedly accelerate grapevine breeding for stress tolerance because elite varieties can be used directly to generate the required epigenetic diversity. For plants like grapevines that have long reproduction phases and are essentially multiplied asexually, epigenetics may provide a quicker and more efficient way to generate cultivars more resilient to the combined stresses generated by climate changes.

For Uruguay viticulture, studying some epigenetics marks in Tannat could be an outstanding tool as an adaptation strategy for climate change and variability. Because of Tannat adaptability and possibly phenotypic plasticity developed in our production systems, we need to deeply research the inter-clonal variability as a breeding tool selection and also find the best clone-rootstock combination (resilience) for a productive perspective to continue to keep and explore Tannat Uruguayan typicity.