Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.18 no.1 Montevideo 2024 Epub 01-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3551

Original Articles

Does deliberation improve civic competences in adolescents? A systematic review of deliberative experiments

1 Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; Conicet, Argentina, anaotto23@hotmail.com

2 Universidad Nacional de Hurlingham; Conicet, Argentina

3 Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; Conicet, Argentina

4 Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; Conicet, Argentina

The deliberation process fosters citizen participation by enhancing civic competences such as political knowledge and interest, argumentative and deliberative quality, levels of political engagement, and tolerance for disagreement. However, is this indeed the case? Which civic competences are effectively modified after participating in a deliberative process? Despite extensive research on adults, there are few studies on adolescence, a pivotal stage for the development of civic competences. A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA method to examine the effects of adolescent deliberation on their civic competences. A total of 252 articles were identified, but only five corresponding to experimental trials and were thus included in the present review. The results indicated that generally deliberation has positive effects on adolescents' civic competences. However, the reported effects are smaller in studies with larger sample sizes, and one study found no effects. Therefore, while there are indications that deliberation can enhance civic competences in adolescents, this enhancement would be modest, and only certain types of interventions would produce it.

Keywords: deliberation; civic competences; adolescents; experimental psychology

El proceso de deliberación fomenta la participación de la ciudadanía al incrementar las competencias cívicas, como el conocimiento y el interés político, la calidad argumentativa y deliberativa, los niveles de cercanía con lo político y la tolerancia al desacuerdo. Sin embargo, ¿es esto realmente así? ¿Cuáles son las competencias cívicas que efectivamente se modifican luego de la participación en un proceso deliberativo? Aunque se ha investigado ampliamente a personas adultas, hay pocos estudios en la adolescencia, etapa crucial para el desarrollo de competencias cívicas. Se realizó una revisión sistemática siguiendo el método PRISMA para examinar los efectos de la participación de adolescentes en la deliberación sobre sus competencias cívicas. Se encontraron 252 artículos, mas solo cinco corresponden a ensayos experimentales y por ello fueron incluidos en la presente revisión. Los resultados indicaron que hay evidencia de que la deliberación tiene efectos positivos sobre las competencias cívicas de las/os adolescentes. Aun así, los efectos reportados son más pequeños en los estudios con mayor tamaño muestral y en un estudio no se encontraron efectos. Entonces, si bien hay indicios de que la deliberación puede mejorar las competencias cívicas en adolescentes, esta mejora sería pequeña y solo algunos tipos de intervenciones la producirían.

Palabras clave: deliberación; competencias cívicas; adolescentes; psicología experimental

O processo de deliberação promove a participação cidadã ao incrementar competências cívicas como o conhecimento e o interesse político, a qualidade argumentativa e deliberativa, os níveis de envolvimento político e a tolerância ao desacordo. No entanto, isso é realmente assim? Quais competências cívicas são efetivamente modificadas após a participação em um processo deliberativo? Embora se tenha investigado amplamente em adultos, há poucos estudos sobre a adolescência, uma fase crucial para o desenvolvimento de competências cívicas. No presente estudo, foi realizada uma revisão sistemática seguindo o método PRISMA para examinar os efeitos da participação de adolescentes na deliberação sobre suas competências cívicas. Foram identificados 252 artigos, mas apenas cinco correspondiam a ensaios experimentais e, portanto, foram incluídos na presente revisão. Os resultados indicaram que há evidências de que a deliberação tem efeitos positivos nas competências cívicas dos adolescentes. No entanto, os efeitos relatados são menores em estudos com amostras maiores, e um estudo não encontrou efeitos. Portanto, embora haja indícios de que a deliberação possa aprimorar as competências cívicas em adolescentes, esse aprimoramento seria modesto, e apenas determinados tipos de intervenções o produziriam.

Palavras-chave: deliberação; competências cívicas; adolescentes; psicologia experimental

Deliberation entails a rigorous analysis of one or several issues, combined with an egalitarian process wherein participants are provided ample opportunities to speak and engage in attentive listening or dialogue that integrates diverse forms of discourse and knowledge (Burkhalter, 2002). Furthermore, it involves a series of moderated discussions among individuals with sufficiently varied opinions to collectively address a clearly identified common problem (Miklikowska et al., 2022) or to reach a decision (Levine, 2018).

In political psychology, deliberative theory posits that collective discussions can enhance understanding and foster positive regard towards individuals with differing worldviews through various avenues: political and affective depolarization (Fishkin et al., 2021), higher levels of political knowledge, improved ability to form reasoned opinions (Andersen & Hansen, 2007), and increased political interest (Miklikowska et al., 2022). Furthermore, Knobloch (2022) argues that following participation in deliberation, individuals seek opportunities for public opinion formation and recognition of interests, equity, and empowerment. Interactions with diverse individuals in these exchanges promote perspective-taking, complex thinking, and political interest, among other competences essential for democratic life (Dewey, 1916, 1980; Fearon, 1998; Habermas, 1996).

Deliberation has also been proposed as a means to enhance argumentative processes. Within the framework of argumentative reasoning theory, deliberation can be understood as a method to improve the quality of argumentative processes and achieve better outcomes (Mercier, 2016). From this perspective, even when reasoning occurs in solitude, it always serves an argumentative function. However, there is an asymmetry in how one evaluates their own arguments compared to those of others: while evaluation of one's own production tends to be vaguer and more biased, evaluation of others' arguments is more rigorous and demands greater objectivity. This is particularly true when these arguments contradict one's own beliefs. Thus, reasoning in heterogeneous groups would be most virtuous, as individuals seeking to persuade others must enhance the quality of their arguments in successive rounds of argumentation. Conversely, when deliberation occurs in groups sharing a viewpoint, new arguments do not conflict with prior beliefs, providing new reasons to uphold them and increasing polarization (e.g., Nyhan & Reifler, 2015).

Participation in a deliberative space where civic-political issues are addressed, and individuals must counter-argue and make a collective decision, could positively impact individuals' civic competences. These civic competences encompass the skills, knowledge, and values necessary for effective and responsible participation in the political and social life of a given community. This entails exercising citizenship in an informed, critical, and committed manner (Gallego, 2017).

In summary, the available evidence suggests that deliberation is associated with the enhancement of civic competences. Various relevant attributes can be used to measure civic competences (Edwards, 2005; McIntosh, 2006; Niemi & Chapman, 1998). Some civic competences are framed within processes of political cognition, such as political knowledge, political interest or attention, political sophistication -a theoretical construct that combines political interest with knowledge about politics (Muñiz et al., 2018), internal political efficacy (Brussino et al., 2006), tolerance of disagreement (Teven et al., 1998), or political tolerance. In contrast, other civic competences are more related to political action: political participation, either factual or the intention to participate collectively in the future (Imhoff & Brussino, 2017), volunteering, conventional and non-conventional activism (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006), among others.

The acquisition of these competences is closely linked to the process of political socialization, which is considered a part of the broader socialization process (Imhoff & Brussino, 2017). Consequently, as individuals assimilate into a specific culture, they simultaneously develop political skills and attitudes that are inherent to that culture. (Benedicto, 1995; Oller Sala, 2008). Imhoff and Brussino (2017) highlight that political socialization entails a process influenced by numerous factors and interactions among different agents and agencies, fostering innovation and social transformation. Additionally, horizontal socialization also holds significance in this process (Amna, 2012); for example, political learning among peers suggests that political socialization occurs within a context of power relations that are more balanced compared to those established with adults (Flanagan, 2003; Pfaff, 2009).

It is noteworthy that adolescence emerges as a pivotal moment within the process of developing civic competences, as youth are particularly receptive to democratic values and principles (Oosterwaal & Op't Eynde, 2017; Flanagan & Faison, 2001; Kahne & Sporte, 2008). Additionally, civic participation during adolescence is associated with civic participation in adulthood, as those who engage in civic activities in their youth are more likely to sustain that commitment throughout their lives (Metzger et al., 2013).

Despite its importance, there is a lack of scientific research on horizontal political socialization, which focuses on peer groups as agents of political socialization, due to an adult-centric view of this process (Pfaff, 2009). Hence, it becomes crucial to address the study of civic competences early in life, with adolescence being a pivotal stage for their formation. Moreover, several studies (e.g., Malaguzzi, 2001; Marina, 2011; Medina & Pérez, 2017; Muñoz, 2010) highlight adolescence as an opportune time for socialization and the development of capacities in younger members of society.

The transformative dimension of civic competences has been explored in previous studies, primarily conducted with adult populations (e.g., Abelson et al., 2002; Chung et al., 2021; Gastil, 2018; Min, 2014; Mühlberger, 2018; Muradova, 2020; Sanjuan & Mantas, 2022). However, research on this issue in youth has been relatively less developed. Therefore, in this study, it is systematically reviewed the existing literature on this topic concerning adolescents. The identified studies are described and synthesized their findings to determine whether participation in deliberative processes enhances various civic competences in adolescents.

Method

To conduct this systematic review (Broome et al., 2006), we followed the guidelines of the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021) for the publication of systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2007). We selected publications reporting results from experimental or quasi-experimental studies evaluating the effect of participation in a deliberative process on various civic competences of adolescents. The research was conducted between July and November, 2022. According to the objectives of this study, the inclusion criteria were:

-Participants were adolescents (10 to 19 years old). Although there is no widespread and exact agreement on which ages fall into the category of "adolescence", according to the traditional definition of the World Health Organization, this period extends from 10 to 19 years, divided into two phases: early adolescence, which spans from 10 to 14 years, and late adolescence, which ranges from 15 to 19 years (Hernández, 1996).

-The study type was an experiment or quasi-experiment.

-The intervention involved participation in a face-to-face deliberation process, with or without a final decision.

-The effects of the intervention were compared with a control or quasi-control group, either passive (a group that does not deliberate or a "waiting list" group) or active (a group engaged in another activity).

-The impact on civic competences was measured, understood broadly as any skill considered a civic competency by the authors of the study.

-The article was published in the last 20 years due to the limited amount of scientific production in the study area that met the selection criteria.

The search terms were selected based on previous literature on deliberation as a process impacting individuals' civic competences.

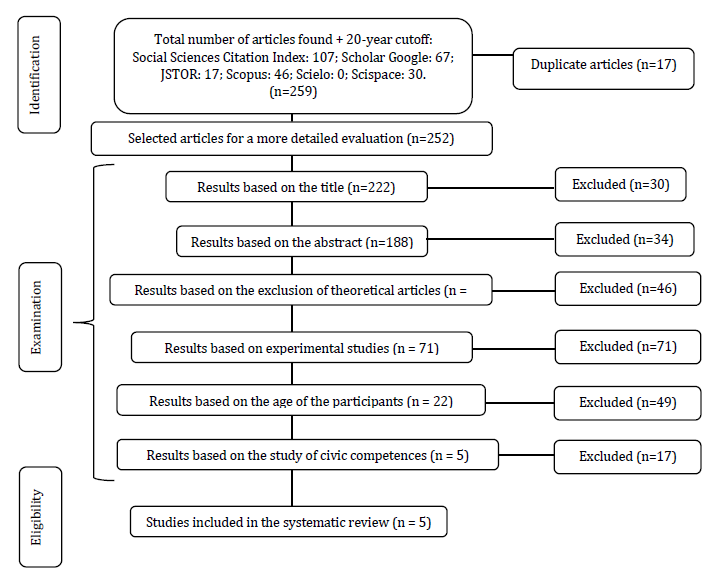

The languages in which the search was conducted were Spanish and English, and the search terms used were as follows: (SPA) deliberación; experimento; adolescentes; competencias cívicas / (ENG) deliberation; experiment; adolescents; civic competences. Likewise, the search engines used were: Social Sciences Citation Index, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Scopus, Scielo, and Scispace. We found that these search engines were the most suitable for exploring the state of scientific production within the field of Political Psychology and related Social Sciences. Figure 1 summarizes the articles found and the selection of these based on the inclusion criteria.

Results

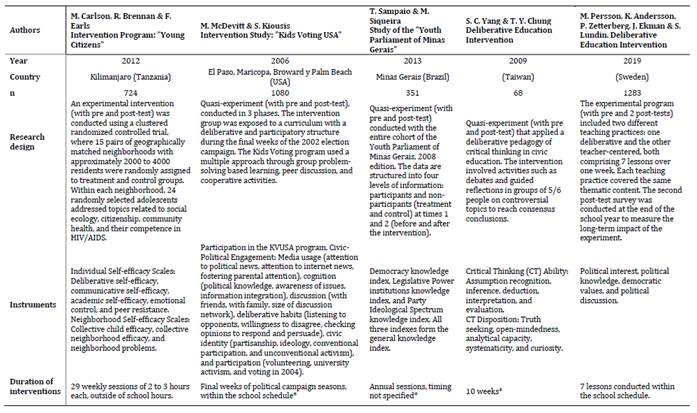

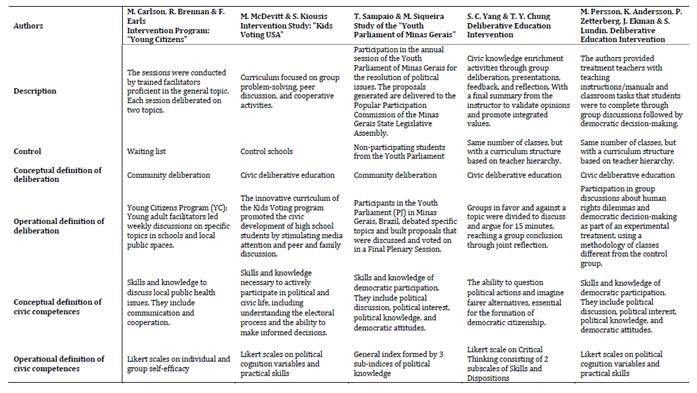

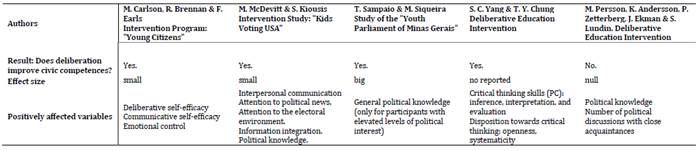

A small number of studies meeting the inclusion criteria were encountered. Most excluded articles were not experimental or quasi-experimental studies and did not involve adolescents as the study population. Overall, the results of the analysis in this review (Table 1 1a 1b) suggest that deliberation has a positive impact on civic competences in adolescents. However, the effect sizes of these interventions tend to be low. In some cases, null effects were found, and in others, while deliberation was shown to improve observed civic competences, effect sizes were not reported. Thus, while deliberation appears to have a positive effect, not every type of intervention yields significant results.

Dependent Variables

The authors of the studies included in this review analyzed various variables as civic competences. These included deliberative self-efficacy, communicative self-efficacy, and emotional control as individual self-efficacy scales (Carlson et al., 2012); media usage, political cognition, political discussion, deliberative habits, civic identity, and participation as civic engagement variables (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006); general political knowledge (Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013); disposition and ability for critical thinking (Yang & Chung, 2009); and political interest, political knowledge, democratic values, and political discussion (Persson et al., 2019).

Political knowledge emerged as the primary dependent variable across the analyzed studies. However, its operationalization varied significantly: McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) and Persson et al. (2019) both assessed political knowledge through questions pertaining to the political system, such as the electoral process and notable political figures at the local level. McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) integrated this measure within their broader assessment of political cognition, which also considered the integration of political information and issue salience. In contrast, Persson et al. (2019) categorized their assessment as factual political knowledge, encompassing inquiries about local and international (European Union) formal politics. On the other hand, Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) devised a more intricate approach to measuring political knowledge. Their methodology involved constructing partial indices concerning knowledge about democracy, legislative institutions, and the ideological spectrum of political parties. These divergent approaches to operationalizing the dependent variable may account for the differing outcomes regarding the positive impact of participation in deliberative processes.

Furthermore, the instruments employed to evaluate political knowledge frequently neglect facets of non-conventional or informal political engagement, which extend beyond the confines of institutional and formal spheres. These realms hold potential significance for political socialization during adolescence (Bruno & Barreiro, 2021). Hence, it becomes pertinent to explore the role of political knowledge using more contextualized and age-appropriate measurements. For instance, inquiries could encompass understanding student politics, gender, or the environment.

Interestingly, in the study by Sampaio and Siqueira (2013), political knowledge increased only among adolescents who had reported higher political interest before deliberation. Even in the study with null effects by Persson et al. (2019), political knowledge increased by an average of 0.3 more correct responses in the intervention group compared to the control group. While this effect is not statistically significant, this data holds substantial interest in contrast to the result of other variables (Persson et al., 2019).

In studies reporting post-intervention improvements (Carlson et al., 2012; McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006; Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013; Yang & Chung, 2009), the enhanced civic competences were primarily associated with heightened levels of political cognition in adolescents. While this aspect of civic competences received the most attention in these investigations, McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) also examined future political electoral participation intention, volunteering, and university activism as civic competences predominantly linked to political action, albeit with reported effect sizes being small.

Similarly, Yang and Chung (2009) discovered that implementing a deliberative curriculum on civic education for adolescents positively impacted overall critical thinking scores. However, while inference, interpretation, and evaluation skills, alongside dispositional openness and systematicity, exhibited significant differences between the experimental and control groups, no statistically significant variances were observed in assumption recognition and deduction skills, nor in truth-seeking disposition, analytical capacity, or curiosity.

In this context, deliberation appears to have influenced civic competences associated with cognitive processes more than those related to political action. However, its impact varies depending on the specific political cognition variables under consideration.

Types of interventions conducted and reported effects

Regarding the reported effect sizes and the methodology leading to these outcomes, McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) conducted a quasi-experiment focusing on the Kids Voting USA program -a deliberative school curriculum implemented in the weeks leading up to local elections-. Their findings revealed that participation in the program positively influenced several factors among adolescents. These included attention to online news (R² = .05), discussions with friends (R² = .03), the size of discussion networks (R² = .04), support for non-conventional activism (R² = .04), volunteering (R² = .07), and engagement in university activism (R² = .07). However, it's worth noting that the reported effect sizes, as previously mentioned, were relatively small. These findings stem from the effects of the deliberative curriculum alone; when incorporating political deliberation within the family in the analysis, the effect size values for attention to political news (R² = .09), attention to news on the internet (R² = .06), and encouraging parental attention (R² = .06) slightly increased. Additionally, political knowledge (R² = .05), information integration (R² = .03), family discussion two years later (R² = .12), willingness to disagree (R² = .03), support for conventional participation (R² = .09) and voting in 2004 (R² = .07) also increased their values following intrafamily deliberation. These results suggest that the program had more pronounced effects on informal political participation forms and peer political action, characterized by more symmetrical power relations. Conversely, with the inclusion of family deliberation in the analysis, the values’ increase was associated with formal political involvement, media usage, and political cognition processes. Furthermore, intrafamily deliberation slightly augmented adolescents' willingness to engage in political disagreement and heightened their efforts to discern the significance or relevance of new political information considering existing knowledge.

On the other hand, Carlson et al. (2012) conducted a cluster randomized controlled trial on 724 adolescents from 30 different neighborhoods. Utilizing software (Optimal Design), the researchers calculated the study's power based on effect size and variation among neighborhoods. The results indicated that post-treatment scores in deliberative self-efficacy (confidence interval, CI = 0.44 - 1.56), communicative self-efficacy (CI = 0.6 - 1.77), and emotional control (CI = 0.05 - 0.77) were significantly higher in the treatment group compared to the control group. However, the effect sizes reported for communicative self-efficacy, deliberative efficacy, and emotional control fall within the range of small effects. Specifically, for the emotional control variable, the effect size was almost null (d = 0.17), for deliberative and communicative efficacy, the effect sizes are small (d = 0.27 and 0.30, respectively; Cohen, 1998).

Furthermore, Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) conducted a quasi-experiment during the annual session of the Youth Parliament (YP) of Minas Gerais in 2008. Participation in the Youth Parliament had a significant effect on participants’ political knowledge compared to the control group (ꞵ = 0.623). Although the long-term effect was negative for most (participants: ꞵ = -0.192 vs. control: -0.027), those participants with an affective relationship with politics experienced a considerable increase in their political knowledge (ꞵ = 1.279). Additionally, the results indicate that being male (ꞵ = 1.130), being in the third year of high school (ꞵ = 1.724), having a propensity for debate (ꞵ = 0.446), having parents with higher education (ꞵ = 1.144), attending a public school (ꞵ = - 0.499), and having participated in other socialization environments before (ꞵ = 0.697) are factors that increase political knowledge when participating in a deliberative instance.

Another study examining the impact of a deliberative school curriculum was conducted by Yang and Chung (2009), involving a quasi-experiment carried out in a high school in southern Taiwan. Initially, the authors found no differences between the groups in the pretest, so they conducted a t-test to compare the posttest results, revealing a statistically significant improvement in the experimental group compared to the control group across several subscales. Specifically, the curriculum demonstrated a positive impact on the following critical thinking skills: Inference (t = 2.20; p = .031), Interpretation (t = 2.69; p = .009), and Evaluation (t = 3.79; p = .001); and on the following critical thinking dispositions: Open-mindedness (t = 3.20; p = .002) and Systematicity (t = 3.50; p = .001). However, no statistically significant differences were observed in critical thinking skills related to: Recognition of Assumptions (t = 1.24; p = .221) and Deductions (t = 1.56; p = .124), nor in critical thinking dispositions Truth-seeking (t = 4.33; p = .666), Analytical Capacity (t = 1.32; p = .190), and Curiosity (t = 1.92; p = .059). Moreover, a qualitative analysis concluded that the intervention significantly enhanced students' ability and disposition to think critically. Taken together, these findings suggest that participants in the experimental group surpassed those in the control group in certain critical thinking skills and dispositions.

The third study, which involved a deliberative school curriculum, was conducted by Persson et al. (2019). They carried out their experiment during the 2015/2016 school year in Sweden but did not yield positive results as anticipated. Despite this, when comparing the differences between the treatment and control groups for each of the eleven individual classroom climate indicators, all variances were statistically significant (ranging between .09 and .14). Students who participated in the deliberative curriculum perceived the classroom climate significantly more open and conducive to deliberation compared to the perception of students in the control group, whose classes were structured based on teacher hierarchy. Although Persson et al.'s (2019) experiment had a positive effect on fostering a more deliberative debate climate in the classrooms, the impact of deliberation on civic competences (such as political interest, democratic values, political knowledge, and political discussions) was small or null (d = -0.012 to d = 0.068). However, upon comparing these findings with those of McDevitt and Kiousis (2006), it is plausible that the favorable outcomes observed in Kids Voting were shaped by the electoral context in which the program operates, as well as the engagement of families after their participation-an aspect lacking in Persson et al.'s (2019) intervention.

Differences in Found Effects

When assessing the research that reported positive effects, the study on the Youth Parliament (Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013) showed a significantly higher effect (R² = .304) compared to evaluations of the Kids Voting USA program (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006) (R² = .05) and Young Citizens (Carlson et al., 2012) (communicative efficacy: d = 0.30; communicative efficacy: d = 0.27). As depicted in Table 1, these deliberative processes are markedly different from each other. Engagement in an institutionalized deliberation such as a Legislative Assembly, yielded superior effects compared to the implementation of deliberative and participatory curricula applied to adolescents over longer periods of time.

On the other hand, literature in the field suggests that both the setting and duration of experiences are influential factors in the impact of deliberative practices on civic competences and their medium-term sustainability (Claes et al., 2017; Geijsel et al., 2012; Gibbs et al., 2021; Hoskins et al., 2012), with those occurring within school institutions and over prolonged periods being deemed the most advantageous. However, the studies analyzed provide evidence that challenges this hypothesis: the largest reported effect size stemmed from the quasi-experiment conducted during the Youth Parliament's annual session, which occurred outside the school institution. Furthermore, Persson et al. (2019) conducted the largest experimental research to date on the effects of deliberation in an educational setting, and contrary to initial theoretical and empirical research, found limited evidence that deliberative education has a positive impact on civic competences.

Different Conceptual and Operational Approaches to Deliberation and Civic Competences

On one hand, McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) and Persson et al. (2019) presented a conceptual definition of deliberative education, while Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) specifically addressed the concept of deliberation, furnishing a clear framework for understanding these ideas within the context of this review. In contrast, Carlson et al.’s (2012) study did not offer explicit conceptual definitions of the notion of deliberation, leaving room for our understanding of their concepts. Similarly, Yang and Chung (2009) also did not clarify a clear definition of deliberative education, leading to interpret their concepts based on their resemblance to other research that explicitly addressed the notion of deliberative education.

Hence, the examined studies delineate two distinct paradigms concerning deliberation: firstly, there exist investigations that conceptualize deliberation as deliberative education (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006; Persson et al., 2019; Yang and Chung, 2009). These studies define deliberative education as a process wherein horizontal learning among peers is fostered through group discussions and reflections, contrasting with educational models centered on teacher hierarchy. Secondly, Carlson et al. (2012) and Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) conceptualize deliberation as the contemplation of diverse perspectives and opinions on issues pertinent to the community. Consequently, deliberation is perceived as actively stimulating debate and collaboratively constructing concrete proposals. Despite the divergence in these approaches, all the studies underscore the interactive and participatory process aimed at reaching shared decisions for collective action.

Regarding the operationalization of deliberation, as delineated in Table 1, Carlson et al. (2012) implemented the Young Citizens program. This initiative engaged adolescents in deliberative activities for approximately two hours per week over a span of 29 weeks, focusing on community health topics. These activities were guided by young facilitators from the community. McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) concentrated on students' involvement in the Kids Voting USA program, which was integrated into high schools. This program utilized problem-solving-based group learning, peer discussion, and cooperative activities. Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) explored deliberation within a session of the Youth Parliament of Minas Gerais in 2008. During this session, adolescents deliberated on political issues through debate and voting on various proposals. In Yang and Chung's study (2009), a deliberative curriculum was implemented over a span of 10 weeks in a high school setting. Students were divided into groups of 6/7 to debate opinions for and against political topics. Subsequently, all participants exchanged views for group decision-making and engaged in reflection on the conclusions drawn. Finally, Persson et al. (2019) implemented a deliberative curriculum in high schools, comprising seven Human Rights education lessons guided by their teacher.

In terms of the conceptual approaches to civic competences, various definitions emerge accentuating both specific skills and political knowledge requisite for active participation in political and civic spheres. Carlson et al. (2012) underscore the significance of skills necessary for discussing and addressing public health issues within the community, including effective communication and fostering cooperation to enhance public health. Conversely, McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) highlight the skills and knowledge essential for active engagement in political and civic life, emphasizing comprehension of the electoral process and the capacity to make informed decisions as foundational elements. Correspondingly, Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) emphasize the importance of political knowledge and political participation skills of citizenship, underlining their pivotal role in strengthening democracy and promoting active and engaged citizenship.

Yang and Chung (2009) and Persson et al. (2019) introduce additional dimensions, such as the essentiality of questioning political actions and imagining fairer alternatives for participatory democracy, as well as the key requirements for democratic participation, including political discussion, political interest, political knowledge, and democratic attitudes. Despite variations in focus and scope, these definitions coalesce around the importance of cultivating skills and knowledge conducive to promoting active citizenship and engendering engagement with political and civic domains.

In conclusion, while the reviewed studies adopt diverse methodological approaches, scales emerge as the most commonly employed tool for assessing civic competences in adolescents. For instance, Sampaio and Siqueira (2013) constructed four indices to gauge the general political knowledge of their participants, whereas Carlson et al. (2012) utilized five scales of individual self-efficacy and four of group self-efficacy to measure adolescents' civic competences. Similarly, both McDevitt and Kiousis (2006) and Persson et al. (2019) employed Likert scales to measure the civic competences outlined in Table 1 across political cognition variables and civic skills. Lastly, Yang and Chung (2009) assessed the critical thinking of their participants through two scales (Critical Thinking Skills and Dispositions), each consisting of five subscales.

Limitations and Strengths of the Included Articles

In general terms, among the five reviewed articles, two are experimental research studies (Carlson et al., 2012; Persson et al., 2019) while the three remaining are quasi-experiments (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006; Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013; Yang & Chung, 2009), as they did not randomly assign participants to treatment and control groups. In McDevitt and Kiousis' study (2006), although the selection process was unbiased, it was not random. Nevertheless, through statistical analysis, they confirmed that there was no significant correlation between participation in the program and the ethnicity, gender, grades, and socioeconomic status of the students and their families; these measures only explain 1% of the variation in students' exposure to Kids Voting USA (R2 = .01).

In McDevitt and Kiousis' study (2006), the sample size was relatively large, not significantly different from the largest experiment in adolescent political deliberation conducted to date (Persson et al., 2019). However, their sample exhibited biases toward individuals from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, and there was a disproportionate loss of minority groups due to attrition at each data collection point. Furthermore, during the third data collection, the sample size was significantly reduced, which limited the statistical power to detect the direct influence of the deliberative curriculum on voting behavior and other behaviors measured at that time (T3). Nonetheless, they did manage to demonstrate indirect effects of the deliberative curriculum.

In Sampaio and Siqueira's study (2013), participants were selected to match the profile of students who had participated in previous editions of the Youth Parliament. Regarding sampling, non-participant Youth Parliament students (totaling 175) selected for participation in the research constituted the control group, while Youth Parliament participants (176 young individuals) comprised the treatment group. Notably, the authors emphasized the predominance of adolescents from elite private schools (n = 99) and young individuals from military public schools (n = 98).

In Carlson et al.'s experimental study (2012), they mitigated the potential for treatment effect diffusion to control neighborhoods by implementing the non-contiguity rule for the random allocation of the intervention. However, an internal validity limitation to consider is that the interviewers were young individuals with prior experience in HIV-related activities but lacked expertise in data collection.

Limitations of Yang and Chung's study (2009) include the absence of information on effect size and the requisite values needed to calculate it, such as the standard deviation of the differences between the means of the experimental and control groups. Consequently, drawing conclusions regarding the impact of the deliberative curriculum on critical thinking in adolescents was not feasible.

On the other hand, the experiment with greater methodological strengths was Persson et al.'s study (2019). Despite designing the largest deliberative experimental study with adolescents, they did not find positive effects. Additionally, this study was strengthened by conducting a deferred application of the post-test questionnaire, administered at the end of the school year, allowing for the measurement of the experiment's impact in the medium term.

Discussion

This review aimed to analyze experimental and quasi-experimental studies investigating the effects of adolescents' participation in deliberative processes on their civic competences, representing the first of its kind to the knowledge of the authors.

One primary finding of this study is the scarcity of experimental research on this topic in adolescent populations, which contrasts with the abundance of evidence available for adult populations. The criteria that led to the exclusion of most initially identified studies were the lack of experimental or quasi-experimental design as well as a lack of focus on adolescent populations. Regarding the former, having experimental evidence is especially relevant as it allows for analyzing the effect of participation in a deliberative process on adolescents' civic competences based on specific and quantifiable data. Additionally, when the methodology is sufficiently detailed, this type of design can be replicated in other settings, enabling comparison of results, validation of findings, and strengthening of identified relationships between variables.

Furthermore, it is worth examining the role of deliberative processes as a tool for political socialization specifically during adolescence, a vital period when individuals begin to become more actively involved in political life. Additionally, it is important to avoid an adult-centric logic of politics that does not recognize young people as active actors in shaping critical citizenship and fostering social transformation (Yarema & Kolchinskaya, 2016).

In summary, the majority of literature exploring the impact of deliberation on adolescents' civic competences consists of theoretical studies (e.g., Avery et al., 2013; Journell, 2010; Levine, 2008), qualitative research (e.g., Crocco et al., 2018; Eränpalo, 2014), or non-experimental investigations (e.g., Lee, 2012; McDevitt & Caton-Rosser, 2009; Maurissen et al., 2018; Yunita et al., 2018). It is worth noting the absence of Spanish-language articles; the sole Latin American study (from Brazil) meeting the selection criteria was the quasi-experiment conducted by Sampaio and Siqueira (2013).

Regarding the analyzed studies (n = 5), the prevailing trend indicates positive impacts. Nonetheless, the extent of improvement varied across civic competences, intervention modalities, and research methodologies. Notably, the experimental study with the largest sample size yielded non-significant results (Persson et al., 2019), and the effect size was unreported in the study by Yang and Chung (2009). In summary, while existing data that suggests that deliberation fosters civic competences, the magnitude of these enhancements appears modest and contingent upon the specific intervention employed. Consequently, certain forms of deliberation may not yield substantial improvements.

The variation in observed effects across studies may be attributed, in part, to differences in political interest. While some studies highlight its pivotal role (Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013), others, such as Persson et al. (2019), do not incorporate it. Future investigations should explore the mediating influence of affective or emotional dimensions of political engagement on both interest and political knowledge. These affective labels serve as cognitive shortcuts, significantly influencing the perceived relevance of issues and the allocation of cognitive resources (von Scheve, 2013). Consequently, specific affective labels, combined with existing political knowledge, facilitate the acquisition of new information and guide citizens' decision-making processes (Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013).

As previously noted, the operationalization of the deliberative process varied in terms of duration and context, posing challenges in identifying a consistent pattern underlying the observed positive effects. Consequently, positive outcomes were evident in diverse settings, ranging from specific experiences (Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013) to prolonged exposure to deliberation (Carlson et al., 2012), with the former appearing to yield more pronounced effects. Moreover, both school-based (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006; Yang & Chung, 2009) and extracurricular (Carlson et al., 2012; Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013) deliberative experiences demonstrated similar efficacy. Despite variations in approach and implementation, all deliberative interventions shared the fundamental characteristic of facilitating face-to-face activities aimed at promoting collective participation and civic education through structured tasks. Additionally, adult guidance or participation was consistent across all interventions, whether as facilitators (Carlson et al., 2012), deliberation guides (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006; Persson et al., 2019; Yang and Chung, 2009), or political knowledge instructors (Sampaio & Siqueira, 2013).

When examining the conceptual approach to deliberation, more similarities than differences among the reviewed studies were identified. Both investigations exploring the effects of deliberative school curricula and those assessing the impact of deliberation beyond the educational sphere underscore its significance as a fundamental process for nurturing civic engagement and reinforcing democratic principles from adolescence onward. Consequently, both conceptualizations highlight the interactive and participatory nature of deliberation among peers aimed at reaching a consensus for collective action.

When rigorously comparing the operationalization of deliberation across the reviewed articles, a nuanced variation tailored to each study was discerned, devoid of replicated designs despite occasional similarities, such as the application of deliberative curricula in secondary schools. However, these interventions varied notably in duration, the thematic scope discussed by participants, and the extent of participant involvement. Consequently, it was deduced that deliberative approaches among adolescents exhibit a remarkable diversity. Given the scant number of studies available, it can be assert that this field of study is in infancy, thereby elucidating the heterogeneous nature of operational approaches.

In examining the conceptual approach to civic competences, a striking convergence emerges across the reviewed studies, wherein they uniformly define such competences as essential civic-political skills or knowledge requisite for active citizenship and fortifying democratic governance. However, this conceptual coherence stands in stark contrast to the varied civic competences measured across the studies. For instance, while political knowledge emerged as a recurrent civic competency in most studies, the array of other civic competences varied based on the authors' discretion in each study. This divergence underscores the diversity in conceptualizing and measuring civic competences, albeit with an underlying interplay between practical skills and cognitive predispositions guiding the selection of competences for measurement. This highlights the importance of integrating both dimensions in future investigations on civic competences in adolescents.

Regarding the civic competences that effectively improved after exposure to a deliberative process, political knowledge increased in all studies where this variable was assessed. However, in Sampaio and Siqueira's study (2013), political knowledge only increased among individuals who had previous political interest before deliberation. Even in Persson et al. (2019), where none of the effects were statistically significant, political knowledge was the variable that showed the greatest growth after deliberation. Other variables that increased in some studies were deliberation and interpersonal communication (Carlson et al., 2012; McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006), attention to political news, electoral attention, integration of information, and issue importance-increasing the degree of importance that adolescents attributed to a particular problem or public controversy- (McDevitt & Kiousis, 2006).

Substantial differences surfaced in the development of adolescents' civic competences depending on the political deliberation process involved. Both peer-driven political socialization and interaction with adults wield distinct impacts on adolescents' political skill development, each contributing uniquely to their civic education. Across the reviewed studies, adolescent-led deliberation nurtured informal political engagement and activism among peers, thereby nurturing the acquisition of political skills and attitudes. Conversely, political deliberations involving adults, within familial or scholastic settings, adopted a more formalized approach, encompassing media utilization, cognitive processes, and conventional political participation. Such engagements augmented adolescents' propensity to engage in political dissent while nurturing endeavors to comprehend the significance and essence of newfound political information.

While these findings hold significance, they also raise certain methodological concerns that warrant attention in forthcoming research endeavors. Primarily, the political knowledge assessments predominantly targeted facets of formal politics, such as voting, sidelining themes and institutions more intertwined with adolescents' daily experiences. It is necessary to understand that adolescent populations may be less engaged with these issues compared to political themes and institutions that are more part of their daily lives (Quintelier & Hooghe, 2013). A measurement of political knowledge for this population should be able to include them. Secondly, most studies focused on dimensions of political cognition while overlooking those pertinent to political action. Future investigations should strive to ascertain whether these competences manifest in concrete political engagement and activity.

In addition to the limitations identified in the reviewed studies, this study also has important constraints. Firstly, the scarcity and diversity of literature in this field impede the drawing of definitive conclusions regarding the impact of deliberation on adolescents' civic competences and the potential mediating factors influencing these effects. Furthermore, the presence of publication bias warrants consideration: there is a greater likelihood of articles reporting significant effects being published compared to those that do not report any effects. Consequently, it would be pertinent to undertake further inquiries aimed at accessing unpublished findings by reaching out to researchers actively engaged in this area of study. Collectively, while the evidence amassed is generally promising, it remains inconclusive at this juncture.

The practical implications of this study prompt the question of whether implementing deliberative interventions on a larger scale among adolescents to promote or enhance their civic competences is viable. The answer is that further experimentation is warranted. This article marks the initial endeavor to investigate and analyze the impacts of deliberative experimental studies on adolescents, addressing a notable gap in Latin American academic literature. Deliberative experimental studies provide individuals with hands-on experience in civic participation, a crucial component for nurturing their civic engagement. Consequently, it is imperative to delve deeper into the study of civic competences, particularly during their formative stages, to uncover avenues for their cultivation. By doing so, we may mitigate levels of political apathy and disinterest stemming from the current crisis in the democratic system.

REFERENCES

Abelson, J., Eyles, J., McLeod, C. B., Collins, P., McMullan, C. & Forest, P. G. (2002). Does deliberation make a difference? Results from a citizens panel study of health goals priority setting. Health Policy, 66(1), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00048-4 [ Links ]

Amna, E. (2012). How is civic engagement developed over time? Emerging answers from a multidisciplinary field. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 611-627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.011 [ Links ]

Andersen, V. N., & Hansen, K. M. (2007). How deliberation makes better citizens: The Danish Deliberative Poll on the euro. European Journal of Political Research, (46), 531-556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00699.x [ Links ]

Avery, P. G., Levy, S. A., & Simmons, A. M. (2013). Deliberating controversial public issues as part of civic education. The Social Studies, 104(3), 105-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2012.691571 [ Links ]

Broome, M. E. (2006). Integrative literature reviews for the development of concepts. En Rodgers, B. L., & Castro, A. (Eds.), Revisão sistemática e meta-análise. [ Links ]

Bruno, D., & Barreiro, A. (2021). Cognitive polyphasia, social representations and political participation in adolescents. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science (55), 18-29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-020-09521-8 [ Links ]

Brussino, S., Sorribas, P., Rabbia, H., & Medrano, L. (2006). Informe investigación. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. [ Links ]

Burkhalter, S. (2002). A conceptual definition and theoretical model of public deliberation in small face-to-face groups. Communication Theory, 12(4), 375-486. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/12.4.398 [ Links ]

Carlson, M., Brennan, R. T., & Earls, F. (2012). Enhancing adolescent self-efficacy and collective efficacy through public engagement around HIV/AIDS competence: A multilevel, cluster randomized-controlled trial. Social Science & Medicine, (75), 1078-1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.035 [ Links ]

Chung, M. L., Fung, K., Chiu, E., & Liu, C. L. (2021). Toward a rational civil society: deliberative thinking, civic participation, and self-efficacy among Taiwanese young adults. Political Studies Review, 20(4), 608-629. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299211024440 [ Links ]

Claes, E., Maurissen, L., & Havermans, N. (2017). Let’s talk politics: Which individual and classroom compositional characteristics matter in classroom discussions? Young, 25(4), 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308816673264 [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1998). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2a ed.). Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Crocco, M. S., Segall, A., Halvorsen, A. L. S., & Jacobsen, R. J. (2018). Deliberating public policy issues with adolescents: Classroom dynamics and sociocultural considerations. Democracy and Education, 26(1), 3. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1916/1980). Democracy and education. En J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works (Vol. 9, pp. 1899-1924). Southern Illinois University Press. [ Links ]

Edwards, S. (2005). National Issues Forums: An alternative to promote students' civic development and community service. Northern Illinois University. [ Links ]

Eränpalo, T. (2014). Exploring Young People's Civic Identities through Gamification: a case study of Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian adolescents playing a social simulation game. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 13(2), 104-120. https://doi.org/10.2304/csee.2014.13.2.104 [ Links ]

Fearon, J. D. (1998). Deliberation as discussion. En J. Elster (Ed.), Deliberative democracy (pp. 44-68). Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fishkin, J., Siu, A., Diamond, L., & Bradburn, N. (2021). Is deliberation an antidote to extreme partisan polarization? Reflections on “America in One Room”. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1464-1481. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000642 [ Links ]

Flanagan, C. (2003). Developmental roots of political engagement. Political Science and Politics, 2, 257-261. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909650300218X [ Links ]

Flanagan, C., & Faison, N. (2001). Youth civic development: Implications of research for social policy and programs. Social Policy Report, 15(3), 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1037/e640322011-002 [ Links ]

Gallego, D. (2017). Competencias ciudadanas y educación ciudadana. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 74(1), 87-106. [ Links ]

Gastil, J. (2018). The lessons and limitations of experiments in democratic deliberation. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 14(1), 271-291. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113639 [ Links ]

Geijsel, F., Ledoux, G., Reumerman, R., & Ten Dam, G. (2012). Citizenship in young people's daily lives: differences in citizenship competences of adolescents in the Netherlands. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(6), 711-729. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.671932 [ Links ]

Gibbs, N. P., Bartlett, T., & Schugurensky, D. (2021). Does school participatory budgeting increase students’ political efficacy? Bandura’s ‘sources’, civic pedagogy, and education for democracy. Curriculum and Teaching, 36(1), 5-27. https://doi.org/10.7459/ct/36.1.02 [ Links ]

Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms. MIT Press. [ Links ]

Hernández C., A. (1996). Familia y adolescencia: Indicadores de salud. En W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Organización Mundial de la Salud & Programa de Salud Integral del Adolescente (Eds.), Manual de aplicación de instrumentos. Coordinación Familia y Población, División de Promoción y Protección de la Salud. [ Links ]

Hoskins, B., Janmaat, J. G., & Villalba, E. (2012). Learning citizenship through social participation outside and inside school: An international, multilevel study of young people’s learning of citizenship. British educational research journal, 38(3), 419-446. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.550271 [ Links ]

Imhoff, D., & Brussino, S. (2017). Socialización política: la dialéctica relación entre individuo y sociedad. En Brussino, S. (Comp.), Políticamente, contribuciones desde la psicología política en Argentina (pp. 37-70). Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas. https://rdu.unc.edu.ar/handle/11086/4910 [ Links ]

Journell, W. (2010). Standardizing citizenship: The potential influence of state curriculum standards on the civic development of adolescents. PS: Political Science & Politics, 43(2), 351-358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096510000272 [ Links ]

Kahne, J., & Sporte, S. E. (2008). Developing citizens: The impact of civic learning opportunities on students' commitment to civic participation. American Educational Research Journal, 45(3), 738-766. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208321459 [ Links ]

Knobloch, K., (2022). Listening to the public: An inductive analysis of the good citizen in a deliberative system. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.16997/10.16997/jdd.955 [ Links ]

Lee, F. L. (2012). Does discussion with disagreement discourage all types of political participation? Survey evidence from Hong Kong. Communication Research, 39(4), 543-562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211398356 [ Links ]

Levine, P. (2008). A Public Voice for Youth: The Audience Problem in Digital Media and Civic Education. En W. Lance Bennett (Ed.), The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning (pp. 119-138). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.1162/dmal.9780262524827.119 [ Links ]

Levine, P. (2018). Deliberation or Simulated Deliberation? Democracy & Education, 26(1), Article 7. https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol26/iss1/7 [ Links ]

Malaguzzi, L. (2001). Educación Infantil en Reggio Emilia. Octaedro. [ Links ]

Marina, J. A. (2011). El cerebro infantil: la gran oportunidad. Ariel. [ Links ]

Maurissen, L., Claes, E., & Barber, C. (2018). Deliberation in citizenship education: how the school context contributes to the development of an open classroom climate. Social Psychology of Education, 21(4), 951-972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9449-7 [ Links ]

McDevitt, M. J & Kiousis, S. (2006). Experiments in Political Socialization: Kids Voting USA as a Model for Civic Education Reform (CIRCLE working paper 49). Center of Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. [ Links ]

McDevitt, M. J., & Caton-Rosser, M. S. (2009). Deliberative barbarians: Reconciling the civic and the agonistic in democratic education. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, 5(2). [ Links ]

McIntosh, H. (2006). The Development of Active Citizenship in Youth. The Catholic University of America. [ Links ]

Medina, J. L., & Pérez, M. J. (2017). La construcción del conocimiento en el proceso de aprender a ser profesor: la visión de los protagonistas. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 21(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v21i1.10350 [ Links ]

Mercier, H. (2016). The argumentative theory: Predictions and empirical evidence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 689-700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.001 [ Links ]

Metzger, A., Flanagan, C., & Syvertsen, A. K. (2013). Youngcitizens and civic learning: Two paradigms of citizenship in the digital age. Citizenship Studies, 17(2), 211-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2013.765542 [ Links ]

Miklikowska, M., Rekker, R., & Kudrnac, A. (2022). A little more conversation a little less prejudice: The role of classroom political discussions for youth’s attitudes toward immigrants. Political Communication, 39(3), 405-427. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2022.2032502 [ Links ]

Min, S.-J. (2014). On the westerness of deliberation research. Journal of Deliberative Democracy , 10(2). https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.207 [ Links ]

Moher, D., Tetzlaff, J., Tricco, A. C., Sampson, M., & Altman, D. G. (2007). Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Med., 4, e78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0468-9 [ Links ]

Mühlberger, P. (2018). Stealth democracy: authoritarianism and democratic deliberation. Journal of Public Deliberation, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.309 [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Téllez, N. M., & Saldierna, A. R. (2017). La sofisticación política como mediadora en la relación entre el consumo de medios y la participación ciudadana: Evidencia desde el modelo OSROR. Comunicación y Sociedad, 30(3), 255-274. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.30.35776 [ Links ]

Muñoz, A. (2010). Psicología del desarrollo en la etapa de Educación Infantil. Pirámide. [ Links ]

Muradova, L., (2020). The challenges of experimenting with citizen deliberation in laboratory settings. En Sage Research Methods Cases Part 1. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529707359 [ Links ]

Niemi, R. G., & Chapman, C. (1998). The Civic Development of 9th Through 12th Grade Students in the United States: 1996. National Center for Education Statistics. [ Links ]

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2015). Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine, 33(3), 459-464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.017 [ Links ]

Oller Sala, M. D. (2008). Socialización y formación política en la democracia española. Iglesia viva: revista de pensamiento cristiano, (234), 7-34. [ Links ]

Oosterwaal, A., & Op't Eynde, P. (2017). Enhancing civic engagement in adolescence: A systematic review of interventions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(8), 1572-1592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0685-5 [ Links ]

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2021.07.010 [ Links ]

Persson, M.; Andersson, K; Zetterberg, P; Ekman, J. & Lundin, S. (2019). Does deliberative education increase civic competence? Results from a field experiment. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1-10 https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2019.29 [ Links ]

Pfaff, N. (2009). Youth culture as a context of political learning. How young people politicize amongst each other. Young , 17(2), 167-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/110330880901700204 [ Links ]

Quintelier, E., & Hooghe, M. (2013). The relationship between political participation intentions of adolescents and a participatory democratic climate at school in 35 countries. Oxford Review of Education, 39(5), 567-589. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.830097 [ Links ]

Sampaio, T., & Siqueira, M. (2013). Impacto da educação cívica sobre o conhecimento político: a experiência do programa Parlamento Jovem de Minas Gerais. Opinão Pública, Campinas, 19(2), 380-402. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-62762013000200006 [ Links ]

Sanjuan, R., & Mantas, E. M. (2022). The effects of controversial classroom debates on political interest: An experimental approach. Journal of Political Science Education, 18(3), 343-361. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2022.2078215 [ Links ]

Teven, J. J.; Richmond, V. P. & McCroskey, J. C. (1998). Measurement of tolerance for disagreement. Communication Research Reports, 15(2), 209-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099809362115 [ Links ]

von Scheve, C. (2013). Emotion and Social Structures: The Affective Foundations of Social Order. Routledge. [ Links ]

Yang, S. C., & Chung, T. Y. (2009). Experimental study of teaching critical thinking in civic education in Taiwanese junior high school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(1), 29-55. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709907x238771 [ Links ]

Yarema, N. A., & Kolchinskaya, V. Y. (2016). Estructura de la socialización política del adolescente. Vector político-l, 1-2. [ Links ]

Yunita, S. A., Soraya, E., & Maryudi, A. (2018). “We are just cheerleaders”: Youth's views on their participation in international forest-related decision-making fora. Forest Policy and Economics, 88, 52-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.12.012 [ Links ]

How to cite: Ottobre Aichino, A. L., Hermida, M. J., Alonso, D., & Brussino, S. (2024). Does deliberation improve civic competences in adolescents? A systematic review of deliberative experiments. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3551. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3551

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. A. L. O. A. has contributed in 1, 2, 5, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14; M. J. H. in 1, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; D. A. in 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14; S. B. in 1, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14.

Received: July 13, 2023; Accepted: May 03, 2024

texto en

texto en