Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Odontoestomatología

versão impressa ISSN 0797-0374versão On-line ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.26 no.43 Montevideo 2024 Epub 01-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.22592/ode2024n43e332

Update

Therapeutic extraction of permanent first molars severely destroyed in mixed denture

1 Departamento de Pediatría Bucal, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Concepción, Región del Biobío, Chile. cfierro@udec.cl

2 Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Concepción, Región del Biobío, Chile.

3 Departamento de Patología y Diagnóstico, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Concepción, Región del Biobío, Chile.

4 Departamento de Pediatría Bucal, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Concepción, Región del Biobío, Chile.

During mixed dentition, the 1st permanent molar is the most susceptible to caries, triggering a repetitive restorative cycle and loss. This study aimed to evaluate determinants of therapeutic extraction of severely damaged 1st permanent molars in mixed dentition before the eruption of the second permanent molar with favorable spontaneous closure of the residual space. The methodology involved a scoping review on PubMed using a specific search strategy. Ten articles were included addressing factors such as the ideal chronological age, stage of development of the second premolar and permanent molar, presence of the third molar, residual spontaneous closure, prognosis, and need for orthodontic treatment. In conclusion, therapeutic extraction of the 1st molar before the eruption of the second molar is associated with favorable spontaneous closure of the residual space. Greater success is evident with the presence of the third molar, the second molar in stage E, and the second premolar in stage F (Demirjian).

Keywords: Molar; Molar hypomineralization; Permanent Molar Primer; Extraction; Dental extraction

En dentición mixta, el 1°Molar permanente es el más susceptible a caries, que desencadena un ciclo restaurador repetitivo y pérdida. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar factores determinantes de la extracción terapéutica de 1°Molares permanentes severamente destruidos en dentición mixta antes de la erupción del segundo molar permanente con un favorable cierre espontáneo del espacio residual. La metodología consistió en una revisión sistemática exploratoria en PubMed mediante búsqueda estratégica/específica. Incluyó diez artículos que abordaron factores como la edad cronológica ideal, etapa de desarrollo del segundo premolar y molar permanente, presencia del tercer molar, cierre espontáneo residual, pronóstico, y necesidad de tratamiento ortodóncico. En conclusión, la extracción terapéutica del 1°Molar antes de la erupción del segundo molar permanente está asociada con un favorable cierre espontáneo del espacio residual. Se evidencia mayor éxito con la presencia del tercer molar, segundo molar en etapa E y segundo premolar en etapa F (Demirjian).

Palabras claves: Molar; Hipomineralización molar; Primer Molar Permanente; Extracción; Extracción dental

Em dentição mista, o 1°molar permanente é o mais suscetível a cáries, desencadeando um ciclo restaurador repetitivo e perda. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar fatores determinantes da extração terapêutica de 1°molares permanentes severamente destruídos na dentição mista antes da erupção do segundo molar permanente com uma região espontânea favorável do espaço residual. A metodología utilizada no PubMed consistiu em uma revisão exploratória por meio de busca estratégica/específica. Foram incluídos dez artigos, abordando fatores como a idade cronológica ideal, estágio de desenvolvimento do segundo pré-molar e molar permanente, presença do terceiro molar, cierre espontâneo residual, pronóstico e necessidade de tratamento ortodôntico. Em conclusão, a extração terapêutica do 1°molar permanente antes da erupção do segundo molar permanente está associada a um fechamento espontâneo favorável do espaço residual. Maior sucesso está descrito quando na presença de terceiro molar, segundo molar no estágio E e segundo pré-molar no estágio F (Demirjian).

Palavras-chave: Molar; Hipomineralização molar; Primer Molar Permanente; Extração; Extração dentária

Introduction:

Most oral diseases, despite being preventable, pose a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide. Untreated dental caries in permanent teeth is the most common health condition. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 2 billion people globally suffer from caries in permanent teeth, while 514 million children are affected by caries in primary teeth1. Among those in mixed dentition, the first permanent molar (FMP) emerges as the tooth most susceptible to this disease2, typically erupting around the age of 6 years. It becomes the first permanent tooth to coexist with the oral environment, featuring multiple cusps and deep grooves3. Furthermore, these teeth are prone to enamel developmental defects such as incisor-molar hypomineralization (IMH). Defined in 2001 by Weerheijm et al., IMH represents a qualitative enamel defect characterized by demarcated opacities and decreased mineral density, primarily affecting at least one FMP, typically the most affected tooth4-6. These lesions can manifest with or without involvement of the incisors, and sometimes affect the second primary molar4-6. This process of dysfunctional enamel mineralization is classified from mild, characterized by demarcated opacities without post-eruptive enamel breakdown (PEB), to severe, involving PEB with pulp compromise (2. The clinical appearance varies from creamy/white to yellow or brown, with or without PEB4. Hypomineralized enamel is less hard and more porous than normal enamel due to its higher protein content. Consequently, it has reduced strength and may lead to PEB soon after tooth eruption or later under the influence of masticatory forces, promoting plaque accumulation and early-onset dental caries2. The overall prevalence of IMH has been determined to be 19%, meaning approximately 1 in 5 children are affected. No differences have been noted regarding sex and geographic location7.

Before determining an appropriate treatment plan for a severely decayed FPM, several factors should be taken into account, including the extent of crown destruction and pulp involvement, the condition of the developing dentition, the severity of dental pain, the attitude of the child and/or parents, the patient's tolerance for prolonged treatment under local anesthesia, socioeconomic factors, and treatment expectations8. Treatment options are diverse; a purely preventive approach may be adopted, especially for mild cases, while restorative approaches using temporary or definitive restorations may be adopted for moderate or severe cases. These may later involve endodontic treatment and prosthetic rehabilitation of the affected teeth9, potentially culminating in tooth extraction at an appropriate or later stage10. As such, with the frequent development of caries and dental fractures in these cases, increasingly complex and repetitive restorative treatments are required, which have an uncertain long-term prognosis10. Consequently, young FPMs with severe damage and pulp involvement often enter a cycle of restorative treatment that ultimately leads to extraction. Nonetheless, if extraction is performed at an appropriate time, it can act as a therapeutic extraction (ExT)9. Therefore, some practitioners advocate for the early extraction of these molars, given their likely poor long-term prognosis and potential future need for extraction.

This study aimed to conduct a Scoping Review to assess the determinants of therapeutic extraction of severely damaged first permanent molars in mixed dentition before the eruption of the second permanent molar, with favorable spontaneous closure of the residual space.

Methodology:

A Scoping Review was performed using the PubMed database. The search strategy incorporated MeSH terms and text words (tw): (Molar*(MeSh) OR "First permanent molar*"(tw)) AND ("Tooth Extraction*"(MeSh) OR Extraction(tw)). Additionally, the search included filters for articles in Spanish or English, studies conducted on humans, and with a publication date no older than 10 years.

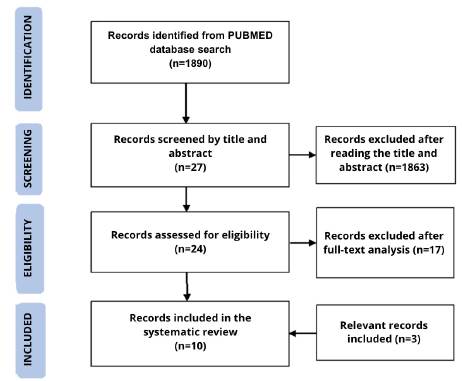

Initially, 1890 articles were identified based on predefined criteria at the identification stage. During the screening phase, 1863 articles unrelated to the study objective were excluded, resulting in the selection of 27 articles. In the eligibility stage, articles that addressed the extraction of FPMs in mixed dentition were considered for inclusion, while those not focusing on FPM ExT, perception surveys, and editorials were excluded. Ultimately, 7 articles meeting these search criteria were included, then, 3 additional articles were added, totaling 10 articles. The search results are detailed in a flow chart adapted and translated from the PRISMA protocol for systematic reviews11. (See Figure 1).

RESULTS:

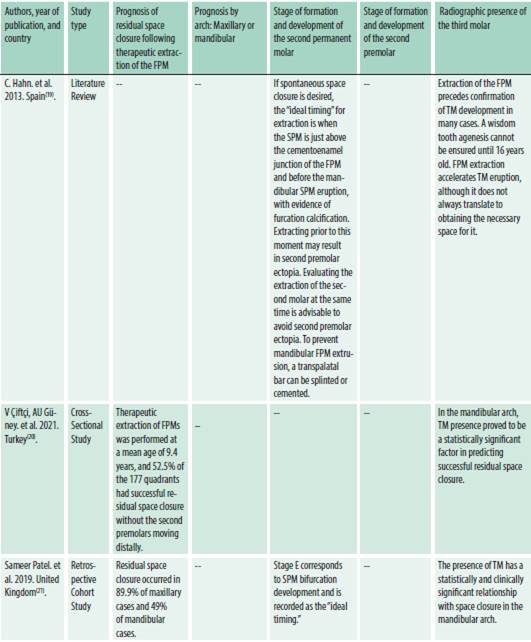

The findings from ten studies assessing the determinants of therapeutic extraction of first permanent molars for spontaneous closure of the residual space were presented in both narrative text and table format (See Table 1).

Ideal chronological age:

Four articles concur that the ideal chronological age for FPM extraction ranges from 8 to 10.5 years12-15. In contrast, three articles suggest an approximate age of 9 years (9, 9.4, and 8 to 9 years)16-18. Among the remaining articles, one does not specify chronological age, implying that timing is not significant19, while another references the stage of formation and dental development of the second permanent molar (SPM), as described by Demirjian, whose method delineates eight stages of calcification for each tooth, denoted by letters A through H, where 0 indicates no calcification20.

Indication for compensating extractions (Extraction of the antagonist) and balancing (Extraction of the contralateral):

Two studies concur that compensating extractions in the mandible are unnecessary for Angle Class II malocclusions(12, 13). However, while one12) suggests the same approach for Class I and II malocclusions12, the other indicates the necessity of compensating extraction of the maxillary FPM specifically in Class I cases13. Regarding mandibular FPM extraction, it emphasizes the necessity for balancing extraction13. Another article argues that in class I, if a maxillary FPM is extracted, compensating extraction is not considered. However, if the mandibular FPM is extracted, compensating extraction is considered. They conclude that in class II, balancing and compensating extractions are not recommended, and in class III, referral to an orthodontist is preferable15.

One article suggests that the traditional approach of compensating for mandibular FPM extraction, and balancing for severe maxillary crowding, has become less common. Instead, alternatives such as anchorage with palatal bars and removable appliances have emerged17.

Factors favoring spontaneous closure between the second permanent molar and the second premolar following therapeutic extraction:

Most authors regard ExT as a successful treatment with a promising long-term prognosis when complete closure of the residual space is achieved. A favorable trend in the prognosis of ExT for maxillary permanent molars compared to mandibular ones is noted. The significance of the development stage of the SPM is emphasized, particularly its presence at Demirjian’s stage E, characterized by the initial formation of the furcation, indicated by a crescent-shaped calcification, and shorter root length compared to the crown. Additionally, the importance of the second premolar being at stage F is highlighted, characterized by well-defined roots, a wider apical portion than the canal diameter, and root length equal to or greater than the crown. Likewise, the relevance of the radiographic presence of the third molar (TM) is stressed12,13,15-17,19-21.

At the same time, it is highlighted that the favorable chronological age for ExT is within the range of 8 to 10.5 years12-18. There is a focus on radiographically observing mesialized angulation of the SPM in relation to the FPM 12,15.

In turn, Alkhadra T. et al. suggest that the extraction of FPMs is feasible when the following factors are present:

Future Orthodontic Treatment Necessity:

In general, the need for post ExT orthodontic treatment is affirmed12-17,19. In Alkhadra T. et al.'s study, the evaluation of malocclusion and implementation of a space maintainer prior to orthodontic intervention are deemed necessary14. Additionally, three radiographic factors are cited as favorable indicators for avoiding future orthodontic treatment: TM presence, the SPM at stage E of development, and the second premolar positioned within the bifurcation of the second primary molar. Conversely, if these factors are absent, post-extraction orthodontic treatment is recommended19.

Consequences of FPM extraction:

It is noted that FPM extraction can have positive effects on the anterior teeth vertically, resulting in a slight overjet and a wider interincisal angle14. Similarly, Saber A. et al. suggest that overbite tends to deepen in over 50% of cases while overjet remains stable, leading to favorable outcomes in the maxilla. Regarding closure of the residual space, spontaneous closure is mentioned as a possibility19,20. Another beneficial effect is the increase in eruption space, thereby reducing the likelihood of impaction of the TM against the SPM. Acceleration in the development and eruption of the SPM is also observed (19. Additionally, C. Hahn et al. suggest that this treatment may benefit individuals with dolichofacial and hyperdivergent craniofacial features17.

On the contrary, unfavorable effects are observed in the mandible. Due to bone characteristics, mesial inclination of the SPM may occur, resulting in residual space 12,14-16,19,20. Similarly, rotation and distal inclination of the second premolar towards the space of the extracted FPM can occur 15,19. Furthermore, there is a possibility of extrusion of the antagonistic FPM following extraction, which can be prevented by splinting or cementing a transpalatal bar (17.

Discussion:

In scientific literature, the indication for compensating extractions (extraction of the antagonist) and balancing extractions (extraction of the contralateral) has been discussed, with various proposals suggesting that these treatments may not be necessary, especially in patients with Angle Class II and dental crowding12,13,15,17. However, the majority of authors assert that orthodontic treatment should follow therapeutic extraction (12-17, 19) .

Determining the ideal chronological age for ExT has also sparked discussion. While some emphasize specific age ranges, such as between 8 and 10.5 years, others focus on the age of 9 years. Some prioritize the developmental stages of the FPM, SPM, and second premolar 12-18.

As a result of the ExT, a verticalization effect on the anterior teeth is observed, characterized by a small or stable overjet, increased interincisal angle, and overbite14. This would be particularly favorable in patients with dolichofacial and hyperdivergent growth patterns17. Additionally, extraction is noted to have a positive impact on the development and eruption of TM, by increasing eruption space and reducing the likelihood of impaction19. Moreover, an early eruption of the SPM is observed20.

Most authors consider ExT a successful treatment with a favorable long-term prognosis when total closure of the residual space is achieved. Furthermore, a higher success rate has been observed in the maxilla, ranging between 70% and 90% of cases. However, this rate decreases to 48% and 49% in mandibular cases13,14,21. Consequently, a positive trend is noted in the prognosis of ExT for maxillary permanent molars compared to mandibular ones. Conversely, Teo T. et al. emphasize that adhering to the three key radiographic factors- development stage of the SPM and second premolar, and the radiographic presence of the TM-can lead to a higher degree of closure of the residual space19. Additionally, M.A. Barceló et al. suggest benefits in crowded dentition and, conversely, advise against ExT in dentitions with diastemas16. Moreover, the decision-making process for ExT in the mandible is complicated by factors such as the mesial inclination of the SPM and chronological age, which simultaneously influence the prognosis and potential sequelae(12, 14-16, 19, 20). Similarly, another factor contributing to a better prognosis is to consider the stage of development of the SPM. Hence, it is crucial to estimate Demirjian’s stage E, observing the early bifurcation of its root12,15,19-21. Also, according to Nolla's classification, the first third of the calcified root -corresponding to stages 6 and 7- should be observed16. Expanding on this, other authors suggest that the SPM should be positioned above the cementoenamel junction of the FPM17) and exhibit a mesial angulation12,19.

Another significant factor to take into account is the development of the second premolar; it is advisable that it reaches Demirjian’s stage F19. Furthermore, it is proposed that the favorable positioning of this second premolar would entail the crown being located within the bifurcation of the second primary molar to avoid collateral effects such as ectopia of the second premolar, i.e., the distal rotation and inclination of this premolar towards the space of the extracted FPM15,19. In this regard, C. Hahn et al. recommend extracting the second primary molar when the SPM exhibits furcation calcification17.

In the mandibular arch, the presence of the TM proves to be a significant factor in predicting successful closure of the residual space18,21. However, its presence cannot always be confirmed, as the appearance of the germ may be delayed12. It is worth noting that following the extraction of the FPM in both jaws, there is an increased likelihood of earlier and adequate eruption of the TM, attributed to the additional eruption space created by the extraction16.

These findings underscore the complexity and necessity of a comprehensive assessment when considering this treatment option in the pediatric population. It is crucial to consider dental maturity, developmental stages, and specific anatomical aspects of each tooth to thoroughly and effectively address strategies for therapeutic extraction.

Conclusion:

Therapeutic extraction of the permanent first molar before the eruption of the second molar (around 9 years of age) can often anticipate favorable spontaneous closure of the residual space, particularly in the maxillary arch. Greater success has been observed when three key radiographic factors are met: presence of the third molar germ, the second molar at Demirjian’s stage E, and the second premolar at Demirjian’s stage F.

REFERENCES

1. Salud bucodental. Who.int (Internet). 2022 (citado el 28 de julio de 2023). Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health [ Links ]

2. Americano, G C A, Jacobsen, P E, Soviero V M, & Haubek D. A systematic review on the association between molar incisor hypomineralization and dental caries. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry (Internet). 2017;27(1):11-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12233 [ Links ]

3. Dastouri M, Kowash M, Al-Halabi M, Salami A, Khamis AH, Hussein I. United Arab Emirates dentists' perceptions about the management of broken down first permanent molars and their enforced extraction in children: a questionnaire survey. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (Internet). 2020 feb 18;21(1):31-41. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40368-019-00434-8 [ Links ]

4. Elhennawy K, Manton D J, Crombie F, Zaslansky P, Radlanski R J, Jost-Brinkmann P-G, y Schwendicke F. Structural, mechanical and chemical evaluation of molar-incisor hypomineralization-affected enamel: A systematic review. Archives of Oral Biology (Internet). 2017;83: 272-281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.08.008 [ Links ]

5. Afshari E, Dehghan F, Vakili MA, Abbasi M. Prevalence of Molar-incisor hypomineralization in Iranian children - A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BDJ Open (Internet). 2022 (citado el 28 de septiembre de 2023); 8(1). Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35697687/ [ Links ]

6. Lygidakis NA, Garot E, Somani C, Taylor GD, Rouas P, Wong FSL. Best clinical practice guidance for clinicians dealing with children presenting with molar-incisor-hypomineralisation (MIH): an updated European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry policy document. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (Internet). 2022 Feb 20;23(1):3-21. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40368-021-00668-5 [ Links ]

7. Lopes L B, Machado V, Mascarenhas P, Mendes JJ y Botelho J. The prevalence of molar-incisor hypomineralization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports (Internet). 2021;11(1):22405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01541-7 [ Links ]

8. Sundfeld D, da Silva L, Kluppel O, Santin G, de Oliveira R, Pacheco R, et al. Molar Incisor Hypomineralization: Etiology, Clinical Aspects, and a Restorative Treatment Case Report. Oper Dent (Internet). 2020 Jul 1; 45(4):343-51. Available from: http://meridian.allenpress.com/operative-dentistry/article/45/4/343/427423/Molar- [ Links ]

9. Sanghvi R, Cant A, de Almeida Neves A, Hosey MT, Banerjee A, Pennington M. Should compromised first permanent molar teeth in children be routinely removed? A health economics analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol (Internet). 2023 51(5):755-66. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12751 [ Links ]

10. Lagarde M, Vennat E, Attal J, Dursun E. Strategies to optimize bonding of adhesive materials to molar-incisor hypomineralization-affected enamel: A systematic review. Int J Paediatr Dent (Internet). 2020 Jul 12;30(4):405-20. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ipd.12621 [ Links ]

11. McKenzie JE, Hetrick SE, Page MJ. Updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews: Introducing PRISMA 2020 to readers of the Journal of Affective Disorders. J Affect Disord (Internet). 2021 (citado el 28 de septiembre de 2023) 292:56-7. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34102548/ [ Links ]

12. Cobourne MT, Williams A, Harrison M. National clinical guidelines for the extraction of first permanent molars in children. Br Dent J (Internet). 2014 Dec 5;217(11):643-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25476643 [ Links ]

13. Eichenberger M, Erb J, Zwahlen M, Schätzle M. The timing of extraction of non-restorable first permanent molars: a systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Dent (Internet). 2015 Dec;16(4):272-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26637248 [ Links ]

14. Alkhadra T. A Systematic Review of the Consequences of Early Extraction of First Permanent First Molar in Different Mixed Dentition Stages. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent (Internet). 2017 Sep 1 7(5):223-6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29026692 [ Links ]

15. Scheu J, Cerda C, Rojas V. Timely extraction of the first permanent molars severely affected in mixed dentition. Journal of Oral Research (Internet). 2019 May 8; 8(3):263-8. Available from: https://www.joralres.com/index.php/JOralRes/article/view/joralres.2019.039/597 [ Links ]

16. Barceló Oliver MA, Cahuana Cárdenas, AB, Hahn, C. Evaluación del cierre espontáneo del espacio residual tras la extracción terapéutica del primer molar permanente. Odontol pediatr 2014 22(2) (cited 2022 Aug 22). Available from: https://www.odontologiapediatrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/259_22.2.orig3.pdf [ Links ]

17. Hahn Chacón C, Cahuana Cárdenas A, Mendes da Silva J, Ustrell Torrent JM, Catalá Pizarro M. Exodoncia terapéutica del primer molar permanente con hipomineralización incisivo molar severa. Revisión de la literatura (Internet). 2013 (cited 2022 Aug 22). Available from: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/123548/1/662517.pdf [ Links ]

18. Ciftci V, Guney A, Deveci C, Sanri I, Salimow F, Tuncer A. Spontaneous space closure following the extraction of the first permanent mandibular molar. Niger J Clin Pract (Internet). 2021 oct 1;24(10):1450. Available from: http://www.njcponline.com/text.asp?2021/24/10/1450/328240 [ Links ]

19. Teo TKY, Ashley PF, Derrick D. Lower first permanent molars: developing better predictors of spontaneous space closure. The European Journal of Orthodontics (Internet). 2016 feb 1;38(1):90-5. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ejo/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/ejo/cjv029 [ Links ]

20. Saber AM, Altoukhi DH, Horaib MF, El-Housseiny AA, Alamoudi NM, Sabbagh HJ. Consequences of early extraction of compromised first permanent molar: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health (Internet). 2018 Dec 5;18(1):59. Available from: https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-018-0516-4 [ Links ]

21. Patel S, Ashley P, Noar J. Radiographic prognostic factors determining spontaneous space closure after loss of the permanent first molar. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics (Internet). 2017 Apr 1;151(4):718-26. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0889540616308757 [ Links ]

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors of this work declare that there is no potential conflict of interest.

Authorship Contribution Note: a) Study conception b) Data acquisition c) Data analysis d) Results discussion and editing e) Manuscript drafting f) Approval of the final version of the manuscript CFM has contributed to a, b, c, d, f CBF has contributed to b, c, d, e,f BGP has contributed to c, d, f APF has contributed to d, e, f

Received: October 02, 2023; Accepted: March 20, 2024

texto em

texto em