Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.18 no.1 Montevideo 2024 Epub 01-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3146

Original Articles

Burnout syndrome, conflicts, emotional labor: discriminating profile between leaders and led

1 Universidade do Vale do Taquari, Brasil, michelletaube@hotmail.com

2 Universidade de Brasília, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Brasil

Workers, both leaders and led, have been exposed to several occupational stressors that, when persistent, can cause Burnout Syndrome. The study aimed to identify the discriminating profile between a group of leading workers and another group of workers, with regard to the dimensions of the Burnout Syndrome (enthusiasm towards job, psychological exhaustion, indolence, guilt), conflict at work (cognitive conflict with task focus, task focus emotional conflict, relationship focus emotional conflict) and emotional labor (demand, dissonance). The sample consisted of 628 workers, 247 leaders and 381 led, who answered the Spanish Burnout Inventory, the Triple Conflict Scale, two subscales of Emotional Work: Emotional Demand and Emotional Dissonance and a questionnaire of sociodemographic and labor data. Data were analyzed using discriminant analysis. The discriminant profile revealed that the group of leaders was distinguished by having more emotional conflict with a focus on the task and emotional demand; the group led showed greater indolence, enthusiasm towards job and guilt. The results make it possible to suggest different actions for the investigated groups.

Keywords: burnout syndrome; conflict at work; emotional work; leadership.

Trabalhadores, tanto líderes como liderados, têm sido expostos a diversos estressores ocupacionais que, quando persistentes, podem ocasionar a síndrome de burnout. O estudo teve como objetivo explorar a diferença entre o grupo de trabalhadores líderes e liderados no que diz respeito às dimensões da síndrome de burnout (ilusão pelo trabalho, desgaste psíquico, indolência, culpa), Conflito no trabalho (conflito cognitivo com foco na tarefa, conflito emocional com foco na tarefa, conflito emocional com foco no relacionamento) e Trabalho emocional (demanda, dissonância). A amostra foi constituída por 628 trabalhadores, 247 líderes e 381 liderados, que responderam ao Spanish Burnout Inventory, à Escala de Conflito Triplo, duas subescalas de Trabalho Emocional: Demanda emocional e Dissonância emocional e um questionário de dados sociodemográficos e laborais. Os dados foram analisados mediante análise discriminante. O perfil discriminante revelou que o grupo dos líderes se diferenciou por ter apresentado mais conflito emocional com foco na tarefa e demanda emocional; o grupo de liderados apresentou maior indolência, ilusão pelo trabalho e culpa. Os resultados possibilitam sugerir ações diferenciadas para os grupos investigados.

Palavras-chave: síndrome de burnout; conflito no trabalho; trabalho emocional; liderança

Los trabajadores, tanto líderes como subordinados, han estado expuestos a varios estresores ocupacionales que, cuando persistentes, pueden causar el síndrome de burnout. El estudio tuvo como objetivo identificar el perfil discriminante entre un grupo de trabajadores líderes y otro grupo de subordinados, con respecto a las dimensiones del síndrome de burnout (Ilusión por el trabajo, Desgaste psíquico, Indolencia, Culpa), Conflicto en el trabajo (Conflicto cognitivo con la tarea centrado en la tarea, conflicto emocional centrado en la tarea, conflicto emocional centrado en la relación) y trabajo emocional (disonancia, demanda). La muestra estuvo conformada por 628 trabajadores, 247 jefes y 381 subordinados, quienes respondieron el Cuestionario para la Evaluación del Síndrome de Quemarse por el Trabajo, la Escala del Triple Conflicto, dos subescalas de Trabajo Emocional: Demanda Emocional y Disonancia Emocional y un cuestionario de evaluación sociodemográfica y laboral. datos. Los datos se analizaron mediante análisis discriminante. El perfil discriminante reveló que el grupo de líderes se distinguió por tener más conflicto emocional con foco en la tarea y demanda emocional; el grupo de subordinados mostró mayores índices en las dimensiones indolencia, ilusión por el trabajo y culpa del síndrome de burnout. Los resultados permiten sugerir diferentes acciones para los grupos investigados.

Palabras clave: síndrome de burnout; conflicto en el trabajo; trabajo emocional; liderazgo

Workers, both leaders and led, are increasingly exposed to stressors in the workplace, which has generated a growth in interest in reducing risks and promoting the health of these two occupational groups (Klebe, 2022). The quality of leadership positively affects the well-being of led (Rudolph et al., 2022) and negatively, such as the occurrence of Burnout Syndrome (BS) (Dyrbye et al., 2020; Parent - Lamarche & Biron, 2022).

A manager’s work causes high psychological demands, often greater than their personal capacity to manage them, which can contribute to occupational stress and the development of BS (Fidelis et al., 2020). The main work demands that can increase the chance of developing the syndrome are role ambiguity, role conflict, stressful events, excessive workload, and pressure from superiors (Laeeque et al., 2018).

Recognized as a psychosocial phenomenon, the syndrome affects many professions due to the constant interpersonal contact and the predominant type of group work in different work contexts (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). Chronic work-related stress leads to SB (Maslach & Leiter, 1997), which stems from a subjective analysis of cognitions, emotions, and negative attitudes towards work (Gil-Monte, 2011).

Gil-Monte (2005) developed a theoretical model consisting of four dimensions: 1) Enthusiasm towards job, characterized by the worker’s desire to achieve their work goals and perceived as a source of personal and professional pleasure. Evaluated inversely, low scores in this dimension indicate high levels of BS; 2) Psychological exhaustion, defined by the emergence of emotional and physical exhaustion resulting from interpersonal relationships established with problematic people; 3) Indolence, described by the presence of feelings of indifference towards customers, colleagues, and the organization; and 4) Guilt, defined as a social emotion linked to interpersonal relationships resulting from negative behavior and attitudes developed at work towards people with whom you need to establish working relationships. The worker perceives a violation of a code of ethics or a social norm inherent in his professional role.

SB results in a series of adverse consequences, both for the individuals affected by it and for the organizations in which these professionals work (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022), as it causes less satisfaction and commitment at work, a greater occurrence of counterproductive behaviors (Lubbadeh, 2021), and higher turnover (De Hert, 2020). Additionally highlighted are the social and economic costs that relational variables found in the workplace context result in most studies (Maslach, 2017). Still, according to the author, this is a serious problem that requires investigations and solutions that involve the development of healthier relationships and organizations.

The characteristics of the position, especially the social and task characteristics, influence the development of SB (Carlotto et al., 2021). It is noteworthy that the syndrome is not only considered an individual issue but a collective phenomenon that impacts people who work in the same group (Llorens & Salanova, 2011).

Work can contribute to the emergence of incompatibilities between team members (O’Neill et al., 2018). Conflicts at work can arise due to failures in communication, competition, a lack of skills and training for conflict management (Deep et al., 2016), and a non-collaborative management style (Edú - Valsania et al., 2022). Interpersonal conflict is a dynamic process that occurs between interdependent individuals as they experience negative emotional reactions, disagreements, and interference in the achievement of their goals (Barki & Hartwick, 2004).

Hjertø and Kuvaas (2017), however, argue that the presence of conflicts in teams does not necessarily generate losses, but rather the types of conflicts that exist. The authors highlight the possibility of three types of conflicts, not defining positive or negative polarity for each of the dimensions: 1) Task-focused cognitive conflict occurs when team members manage to combine intense, task-oriented communication with an emotional climate positive for group performance; 2) Emotional conflict with a focus on the task is described as emotional, as strong emotional reactions to tasks are not personal and remain focused on the task; 3) Relationship-focused emotional conflict is characterized by the perception of the existence of simultaneous and incompatible approval or avoidance issues between group members in relation to issues related to the person.

Interpersonal conflicts represent a social stressor (Akhlaghimofrad & Farmanesh, 2021) and can compromise people’s work negatively (De Wit et al., 2012). In this sense, it is up to the leader to develop strategies that aim to alleviate conflicts or manage them (Jeung et al., 2018). Studies have identified the predictive role of interpersonal conflicts at work for BS (Danauskė et al., 2023; Llorca-Pellicer et al., 2021).

One of the great attributes of leadership is the ability to resolve conflicts, manage them, and mitigate their impact. However, the leader himself may find himself in conflict situations, especially regarding disagreements between the leader and the led (Martins et al., 2014). When these divergences occur while performing tasks and the worker does not have social support, the feeling of dissatisfaction at work increases (Resende et al., 2010). When well-managed, conflicts can generate significant learning (Shah et al., 2021) and increase well-being and positive emotions at work (Salas-Vallina et al., 2020).

Conflicts at work imply emotional labor (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022), as they activate sometimes ambivalent emotions, causing lower psychological well-being and SB (Oh, 2022). Emotional work is a psychological process characterized by the worker’s effort to regulate their emotions to meet the emotional demands of work with the aim of demonstrating the desired emotions in the work context, with this demonstration sometimes being contrary to the emotion felt (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022). It is generally associated with two dimensions: emotional demands, determined by the frequency of interpersonal interactions, and emotional dissonance, characterized as the conflict between emotions felt and expressed in the organizational context (van Dijk & Brown, 2006).

Emotions influence human behavior and have an impact on the relationship with the leader. The perception by led workers that the leader cares about their needs and values their performance contributes to greater commitment to the organization through positive attitudes towards work (Nascimento & Bryto, 2019). Thus, the leader’s behavior can positively or negatively influence the emotional state of their led (Top et al., 2020).

Leadership presents frequent interactions with people, a context that increases the need to regulate emotional manifestations (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). The leader’s emotional regulation strategies play a fundamental role in improving or damaging the quality of the relationship between leaders and led (Moin et al., 2021).

Although they carry out their work together, leaders and led present functional, motivational, emotional, and behavioral differences. Subordinates have less power, authority, flexibility, and influence than their superiors (Antelo et al., 2010).

Thus, identifying the discriminating profile can help professionals plan interventions according to the specificity of each occupational group (Jin et al., 2015). Based on the above, this study, with a quantitative method and exploratory, analytical, and cross-sectional design, aimed to explore the differences between the groups of leading and led workers with regard to the dimensions of BS (enthusiasm towards job, psychological exhaustion, indolence, and guilt), Conflict at work (task-focused cognitive conflict, task-focused emotional conflict, and relationship-focused emotional conflict), and Emotional labor (emotional dissonance and emotional demand).

Method

Participants

The investigation involved the participation of 247 (39.3 %) leaders and 381 (60.7 %) employees who had been working for more than a year and who did not necessarily work in the same organization. In the group of led, the majority declared themselves to be female (65.4%), with a steady partner (78.6 %), without children (57.5 %), with an average age of 34.46 years (SD= 10.27) and education at the undergraduate or specialization level (64.6 %). Also, the majority worked exclusively at their current place of work (80.6 %), in a private company (88.7 %), and with an employment contract (87.4 %). The average working time in the current company was 7.11 years (SD= 7.31).

In the group of leaders, the majority declared themselves to be male (56.7 %), with a steady partner (90.7 %), with children (71.7 %), an average age of 41,10 years (SD= 8.56) and education at the undergraduate or specialization level (77.7 %). Also, the majority worked for a private company (85.4 %) and had an employment contract (68.4 %). The average working time in the current company was 9.55 years (SD= 8.12).

Instruments

A sociodemographic and employment data questionnaire. Sociodemographic (gender, age, marital status, children, training) and labor (time working in current job, type of company (public or private), type of relationship (statutory or CLT).

Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI) by Gil-Monte (2005), version adapted for use in Brazil by Gil - Monte et al. (2010). The instrument has 20 items distributed across four subscales: Enthusiasm towards job (five items, α = .72, in this study, α = .91; ex. item: my work represents a stimulating challenge for me); Psychological exhaustion (four items, α = .86, in this study, α = .87; ex. item: I feel pressured by work); Indolence (six items, α = .75, in this study, α = .76; ex. item: I think I treat some people with indifference); Guilt (five items, α = .79, in this study, α = .81; ex. item: I feel bad about some things I said at work). We rated the items on a four-point frequency scale, which ranged from (0) never to (4) every day.

The Triple Conflict Scale was developed by Hjertø and Kuvaas (2017) and adapted in Brazil by Oliveira and Mourão (2021). This is a 10-item, three-dimensional scale that assesses three types of conflicts: Cognitive conflict with a focus on the task (four items; α = .72, in this study, α = .74; ex. item: during the conflict, the group is concerned with resolving problems using sensible and rational procedures); Emotional conflict with a focus on the task (three items; α = .67, in this study, α = .71; ex. item: discussions in the team are intense, but our intention is to find the best alternative for the work); and Emotional conflict focusing on relationships (three items; α = .68, in this study, α = .60; ex. item: conflicts in the group are guided by feelings of envy and a less open mentality). We answered the items on a five-point Likert scale, which ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Emotional labor, assessed by two subscales: 1. Emotional work, assessed by two subscales: 1. Emotional demand - Questionnaire on the Experience and Assessment of Work (QEEW) by van Veldhoven et al. (2002), translated and adapted for the present study (seven items, α = .71, in this study, α = .78; ex. item: How often, in your work, do you have contact with difficult people?). Items were rated on a four-point frequency scale, ranging from (1) never to (4) always; 2. Emotional dissonance - Frankfurt Emotion Work Scales (FEWS) by Zapf et al. (1999), translated and adapted for the present study (five items, α = .79; in this study, α = .83; ex. item: During your work, do you need to express positive feelings towards people while you, in reality, feel indifferent?). We evaluate the items using a five-point frequency scale, which ranges from (1) never to (5) very often.

Data collection procedures

We collected data using an online platform. We used the snowball technique to recruit participants, asking participants to respond to the survey and then forward it to other potential participants (Leighton et al., 2021). We collected the data between July and November 2021. Under CAEE number 46858121.9.0000.5344, the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brazil, approved the investigation.

Data analysis procedures

We analyzed the data using a statistical package. Initially, we performed descriptive analyses to estimate frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations to characterize the sample.

Next, we compared the means of each group in these variables using the student’s t test. Finally, a discriminant analysis was carried out using the stepwise method with the discriminant profile of the dimensions of BS (enthusiasm towards job, psychological exhaustion, indolence, guilt), conflict at work (cognitive conflict focused on the task, task-focused emotional conflict, relationship-focused emotional conflict), and emotional labor (emotional dissonance, emotional demands). The discriminant analysis used leaders and led as grouping variables. The results were considered significant at a p value < .05.

Results

Table 1 presents the variables under study in the comparison of averages between leaders and led. We found that leaders have higher means in cognitive conflicts with a task focus (M= 3.69; SD= 0.67) and emotional conflicts with a task focus (M= 3.48; SD= 0.73). They also have higher means in the emotional demand dimension (M= 2.66; SD= 0.45). Those led had higher means in three dimensions of BS: enthusiasm towards job (M= 2.39; SD= 0.83), psychological exhaustion (M= 3.06; SD= 0.77), and indolence (M= 2.19; SD= 0.59).

Table 1: Comparison of means of study variables between the groups of led (n= 381) and leaders (n= 247)

* p< .05 **p< .01 a variable not used in the analysis

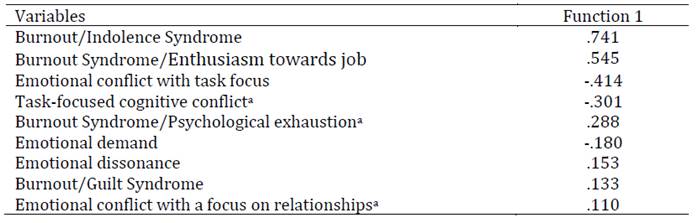

We subjected all variables under study to discriminant analysis. The discriminant function presented an eigenvalue of .189. This function, being unique, explained 100 % of the total variability found between the groups, with a canonical correlation between the profile and the function of .399. Wilk’s lambda revealed that it is possible to explain 84.1 % (l-Wilks) of the existing variance. The function found was significant at p < .001.

There was a good prediction capacity, with a general result that correctly classified 68 % of the cases into the discriminated groups. The lead group was the one that fit the profile most precisely, with 68.8 % of cases well classified. The percentage of well-classified cases in the leader group was slightly lower (66.8 %).

The function distanced the group of led with a centroid of .350, from the leaders, whose centroid is -.539. The centroid functions as a central point for the degree of dispersion of cases in the discriminated clusters. It was identified that the variables that differentiated the groups were indolence (.741), enthusiasm towards job (.545), emotional conflict with focus on the task (-.414), emotional demand (-.180) and guilt (.133). The group of leaders differed by presenting more emotional conflict with focus on the task and greater emotional demand; the group of led showed greater indolence, illusion, and guilt. The variables cognitive conflict with a focus on the task, psychological exhaustion, emotional dissonance, and emotional conflict with a focus on relationships did not differentiate the groups (Table 2).

Discussion

The present study sought to explore the differences between the group of led workers and leaders with regard to the dimensions of BS, conflict at work, and emotional labor. The results revealed that leaders differentiated themselves by presenting higher levels of emotional conflict, with a focus on the task and emotional demand at work. The group of led showed greater indolence, enthusiasm towards job, and guilt.

The result, regarding greater emotional conflict with a focus on the task in leaders, reveals an important positive difference regarding the characteristics of the work of these managers, as it indicates the existence of a way of dealing with conflict in a healthy way, aiming for better performance and team satisfaction. In this type of conflict, leadership explores the best solution and alternative while simultaneously dealing with emotions without losing sight of the task or solving a problem (Hjertø & Kuvaas, 2017).

It is possible to think that the group of leaders presents a transformational leadership style, defined, among other characteristics, by adopting new ways of solving problems and thinking and questioning old assumptions, with transformational leadership being the one that most contributes to avoiding a conflictual environment. (Tanveer et al., 2018). This finding could potentially clarify why none of the BS dimensions demonstrated discrimination in this group.

The task-focused emotional conflict dimension consists of strong emotional reactions to tasks. This, however, does not represent personal reactions, so the focus is on the task (Hjertø & Kuvaas, 2017) and concerns an important leadership function in this case, the positive management of conflicts in your work group. Conflicts can lead to tension, harm the health of those under leadership, cause delays in decision-making, lead to emotional exhaustion, increase turnover rates, and jeopardize professional and organizational development actions (Kammerhoff et al., 2019).

Despite the negative connotation of conflicts, functional and friendly relationships can help workers and organizations achieve positive results and contribute to a constructive understanding of the conflict (Tanveer et al., 2018). The leader has a prominent role in managing and impacting conflicts on the team due to his role as authority. However, eventually, the leader himself becomes involved in conflictual situations, due to disagreements or divergences that can generate dissonance among the team. Considering conflict as a natural consequence of social interactions, intrinsic to human relationships, it follows that managers have a fundamental role in various organizational processes. They are responsible for project management and have the power to implement or interrupt them, even in difficult work contexts and with conflicting priorities (Nielsen et al., 2017).

Regarding the result of greater emotional demand, the literature has highlighted that leaders need to manage their emotions due to the responsibilities they have in the work process, and one of their competencies consists of reducing the impact of emotions in the communication process and directing activities and demands received (Silard & Dasborough, 2021). Thus, there is growing recognition that leaders must demonstrate emotions to achieve organizational goals (Cavazotte et al., 2021; Rajah et al., 2011). Leaders’ emotions have important effects on led and impact the relationship between them, with the quality of this interaction depending on the direction of the emotions. It can be considered that leaders’ emotional expressions shape the emotions of their led (Silard & Dasborough, 2021).

In the group of led the variables that differentiate it from the group of leaders are the dimensions of SB, that is, greater enthusiasm towards job, indolence, and guilt. Due to functional differences, we can assume that employees have a greater desire to achieve their work goals and perceive this as a source of personal pleasure. When comparing groups of leaders and led, Wallis et al. (2021) found that led had better results in terms of their well-being and life satisfaction because they experienced less work overload and more social support from peers. The result confirms a study by Cavanaugh et al. (2020), who identified higher levels of the syndrome in workers who did not hold leadership positions. The leader’s behavior pattern has an influence on the led’ involvement in BS, whether it is providing support resources and promoting well-being or imposing demands that can exhaust employees’ resources (Dyrbye et al., 2020).

The discriminant profile identified that the group of leaders presented greater emotional conflict with a focus on the task and greater emotional demand, while the group of led presented greater indolence, enthusiasm towards job, and guilt. In this sense, the results allow us to suggest different actions for the groups investigated. For leaders, interventions aimed at developing emotional regulation strategies to deal with the emotional demands arising from work relationships, in addition to the emotions arising from task-focused conflicts, are important. For those led, actions aimed at occupational stressors and BS are suggested, which can lead to detachment and feelings of guilt related to work.

The study has some limitations, such as the use of self-report instruments, which can cause bias in the results, especially when using emotional variables. The snowball technique recruits a non-random sample, which hinders the generalization of the results. We also highlight the different contexts and organizational characteristics of the participants, such as the size of the company and the number of workers in the work groups, which can impact the results obtained.

Therefore, to provide dyadic analysis using new variables such as motivation/regulatory focus, occupational stressors, and coping strategies used in stress management, we recommend that future studies use random samples with data collection from leaders and their subordinates paired. Equally important is the development of new studies with more homogeneous organizations and work teams.

REFERENCES

Akhlaghimofrad, A., & Farmanesh, P. (2021). The association between interpersonal conflict, turnover intention and knowledge hiding: The mediating role of employee cynicism and moderating role of emotional intelligence. Management Science Letters, 11, 2081-2090. http://dx.doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2021.3.001 [ Links ]

Antelo, A., Prilipko, E. V., & Sheridan-Pereira, M. (2010). Assessing effective attributes of followers in a leadership process. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 3(9), 33-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.19030/cier.v3i10.234 [ Links ]

Barki, H., & J. Hartwick (2004). Conceptualizing the construct of interpersonal conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 15(3), 216-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb022913 [ Links ]

Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work”. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 17-39. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815 [ Links ]

Carlotto, M. S., Abbad, G. da S., Sticca, M. G., Carvalho-Freitas, M. N. de, & Oliveira, M. S. de. (2021). Burnout syndrome and the work design of education and health care professionals. Psico-USF, 26(2), 291-303. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712021260208 [ Links ]

Cavazotte, F., Abelha, D. M., & Turano, L. M. (2021). Effects of emotion displays on followers’ perceptions of principled leaders. Brazilian Administration Review, 18(1), e190142. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-7692bar2021190142 [ Links ]

Cavanaugh, K. J., Lee, H. Y., Daum, D., Chang, S., Izzo, J. G., Kowalski, A., & Holladay, C. L. (2020). An examination of burnout predictors: Understanding the influence of job attitudes and environment. Healthcare, 8(4), 502. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040502 [ Links ]

Danauskė, E., Raišienė, A. G., & Korsakienė, R. (2023). Coping with burnout? Measuring the links between workplace conflicts, work-related stress, and burnout. Business: Theory and Practice, 24(1), 58-69. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2023.16953 [ Links ]

Deep, S., Othman, H., & Mohd Salleh, B. (2016). Potential causes and outcomes of communication conflicts at the workplace - a qualitative study in Pakistan. Journal of Management Info, 3(3), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.31580/jmi.v11i1.54 [ Links ]

De Hert, S. (2020). Burnout in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence, Impact and Preventative Strategies. Local and Regional Anesthesia, 13, 171-183. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S240564 [ Links ]

De Wit, F. R. C., Greer, L. L., & Jehn, K. A. (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: a meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 360-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024844 [ Links ]

Dyrbye, L. N., Major-Elechi, B. J., Hays, J. T., Fraser, C. H., Buskirk, S. J., & West, C. P. (2020). Relationship between organizational leadership and health care employee burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 95(4), 698-708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.10.041 [ Links ]

Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031780 [ Links ]

Fidelis, J. F., Zille, L. P., & Rezende, F. V. de. (2020). Estresse e trabalho: O drama dos gestores de pessoas nas organizações contemporâneas. Revista de Carreiras e Pessoas, 10(3), 466-485. http://dx.doi.org/10.20503/recape. v10i3.49552 [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R (2005). El síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo (burnout). Una enfermedad laboral en la sociedad del bienestar. Pirâmide. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. (2011). CESQT - Cuestionario para la evaluación del síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo: Manual. TEA. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R., Carlotto, M. S., & Câmara, S. G. (2010). Validação da versão brasileira do “Cuestionario para la Evaluación del Síndrome de Quemarse por el Trabajo” em professores. Revista de Saúde Pública, 44(1), 140-147. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102010000100015 [ Links ]

Hjertø, K., & Kuvaas, B. (2017). Burning hearts in conflict: New perspectives on the intragroup conflict and team effectiveness relationship. International Journal of Conflict Management, 28(1), 50-73. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-02-2016-0009 [ Links ]

Jeung, D. Y., Kim, C., & Chang, S. J. (2018). Emotional labor and burnout: A review of the literature. Yonsei Medical Journal, 59(2), 187-193. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2018.59.2.187 [ Links ]

Jin, Y. Y., Noh, H., Shin, H., & Lee, S. M. (2015). A typology of burnout among Korean teachers. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24, 309-318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-014-0181-6 [ Links ]

Kammerhoff, J., Lauenstein, O., & Schütz, A. (2019). Leading toward harmony- Different types of conflict mediate how followers’ perceptions of transformational leadership are related to job satisfaction and performance. European Management Journal, 37(2), 210-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.06.003 [ Links ]

Klebe, L., Felfe, J., & Klug, K. (2022). Mission impossible? Effects of crisis, leader and follower strain on health-oriented leadership. European Management Journal, 40(3), 384-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.07.001 [ Links ]

Laeeque, S. H., Bilal, A., Babar, S., Khan, Z., & Rahman, S. U. (2018). How patient-perpetrated workplace violence leads to turnover intention among nurses: The mediating mechanism of occupational stress and burnout. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(1), 96-118. http://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1410751 [ Links ]

Leighton, K., Kardong-Edgren, S., Schneidereith, T., & Foisy-Doll, C. (2021). Using social media and snowball sampling as an alternative recruitment strategy for research. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 55, 37-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.03.006 [ Links ]

Llorca-Pellicer, M., Soto-Rubio, A., &. Gil-Monte, P. R. (2021). Development of burnout syndrome in non-university teachers: influence of demand and resource variables. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644025 [ Links ]

Llorens G.S., & Salanova S., M. (2011). Burnout: Un problema psicológico y social. Riesgo Laboral, 37, 26-28. [ Links ]

Lubbadeh, T. (2021). Job burnout and counterproductive work behaviour of the Jordanian bank employees. Organizacija, 54(1), 50-62. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2021-0004 [ Links ]

Martins, M. C. F, Abad, A. Z., & Peiró, J. M. (2014). Conflitos no ambiente organizacional. Em M. M. M. Siqueira (Org.), Novas medidas do comportamento organizacional. ferramentas de diagnóstico e de gestão, (pp. 132-146). Artmed. [ Links ]

Maslach, C. (2017). Finding solutions to the problem of burnout. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(2), 143-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000090 [ Links ]

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Moin, M. F., Wei, F., Weng, O., & Bodla, A. A. (2021). Leader emotion regulation, leader-member exchange (LMX), and followers’ task performance. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(3), 418-425. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12709 [ Links ]

Nascimento, L., & Bryto, K. (2019). A influência da liderança na produtividade organizacional: Estudo de caso na empresa Solus Tecnologia. RAC: Revista de Administração e Contabilidade, 6(11), 31-44. [ Links ]

Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1304463 [ Links ]

Oh, V. Y. S. (2022). Torn between valences: Mixed emotions predict poorer psychological well-being and job burnout. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23, 2171-2200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00493-z [ Links ]

Oliveira, D., & Mourão, L. (2021). Adaptação cultural para a população brasileira da Escala de Conflito Triplo. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 41, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703003223431 [ Links ]

O’Neill, T. A., McLarnon, M. J. W., Hoffart, G., Onen, D., & Rosehart, W. (2018). The multilevel nomological net of team conflict profiles. International Journal of Conflict Management, 29(1), 24-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-05-2016-0038 [ Links ]

Parent-Lamarche, A., & Biron, C. (2022). When bosses are burned out: Psychosocial safety climate and its effect on managerial quality. International Journal of Stress Management, 29(3), 219-228 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/str0000252 [ Links ]

Rajah, R., Song, Z., & Arvey, R. D. (2011). Emotionality and leadership: Taking stock of the past decade of research. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1107-1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.09.006 [ Links ]

Resende, P. C., Martins, M. C. F., & Siqueira, M. M. M. (2010). Bem-estar no trabalho: influência das bases de poder do supervisor e dos tipos de conflito. Mudanças - Psicologia da Saúde, 18(1-2), 47-57. [ Links ]

Rudolph, C. W., Breevaart, K., & Zacher, H. (2022). Disentangling between-person and reciprocal within-person relations among perceived leadership and employee wellbeing. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(4), 441-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000320 [ Links ]

Salas-Vallina, A., Simone, C., & Fernández-Guerrero, R. (2020). The human side of leadership: Inspirational leadership effects on follower characteristics and happiness at work (HAW). Journal of Business Research, 107, 162-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.044 [ Links ]

Silard, A., & Dasborough, M. T. (2021). Beyond emotion valence and arousal: A new focus on the target of leader emotion expression within leader-member dyads. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(9), 1186-1201. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2513 [ Links ]

Shah, P. P., Peterson, R. S., Jones, S. L., & Ferguson, A. J. (2021). Things are not always what they seem: The origins and evolution of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 66(2), 426-474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839220965186 [ Links ]

Tanveer, Y., Jiayin, Q., Akram, U., & Tariq, A. (2018). Antecedents of frontline manager handling relationship conflicts. International Journal of Conflict Management, 29(1), 2-23. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-03-2017-0021 [ Links ]

Top, C., Abdullah, B., & Faraj, A. (2020). Transformational leadership impact on employee’s performance. Eurasian Journal of Management & Social Sciences, 1(1), 49-59. https://doi.org/10.23918/ejmss.v1i1p49 [ Links ]

Wallis, A., Robertson, J., Bloore, R. A., & Jose, P. E. (2021). Differences and similarities between leaders and non leaders on psychological distress, well-being, and challenges at work. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 73(4), 325-348. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/d648u [ Links ]

van Dijk, P. A., & Brown, A. K. (2006). Emotional labour and negative job outcomes: An evaluation of the mediating role of emotional dissonance. Journal of Management & Organization, 12(02), 101-115. http://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2006.12.2.101 [ Links ]

van Veldhoven, M., De Jonge, J., Broersen, S., Kompier, M., & Meijman, T. (2002). Specific relationships between psychosocial job conditions and job related stress: A three-level analytic approach. Work and Stress, 16, 207-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370210166399 [ Links ]

Zapf, D., Mertini, H., Seifert, C., Vogt, C., & Isic, A. (1999). Frankfurt Emotion Work Scales - Frankfurter Skalen zur Emotionsarbeit FEWS 3.0. Department of Psychology, J. W. Goethe-University Frankfurt. [ Links ]

How to cite: Engers Taube, M., Carlotto, M. S., & Gonçalves Câmara, S. (2024). Síndrome de burnout, conflitos, trabalho emocional: perfil discriminante entre líderes e liderados. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3146. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3146

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. M. E. T. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14; M. S. C. in 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14; S. G. C. in 3, 6, 10, 11, 12, 14.

Received: December 13, 2022; Accepted: March 14, 2024

texto en

texto en

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI