Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.18 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2024 Epub 01-Dic-2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3833

Original Articles

Spiritual well-being and its influence on forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience in university students in Lima (Peru)

1 Universidad Marcelino Champagnat, Perú,

2 Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Perú

3 Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Perú, jossue.correa@upc.pe

4 Universidad César Vallejo, Perú

4 Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Perú

This study aimed to determine the influence of spiritual well-being on gratitude, forgiveness, and resilience in university students in the city of Lima. An explanatory design with latent variables was used. The sample consisted of 957 university students (29.5 % men and 70.5 % women from 13 universities (22.36% public and 77.64 % private)), from Metropolitan Lima. The Spiritual Wellbeing Scale (SWBS), the Trait Forgivingness Scale (TFS), the Gratitude Scale (GS), and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) were used. Among the findings, it was found that the model estimated with the DWLS method allows us to point out that spiritual well-being directly affects forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience. In turn, the covariance between forgiveness and gratitude was .090 (p > .05), the covariance between forgiveness and resilience was .236 (p < .01), and the covariance between gratitude and resilience was equal to .122 (p < .01). The implications of the results have been discussed.

Keywords: spiritual well-being; forgiveness; gratitude; resilience; university students; positive psychology

El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la influencia del bienestar espiritual en la gratitud, el perdón y la resiliencia en estudiantes universitarios de la ciudad de Lima. Se utilizó un diseño explicativo con variables latentes. La muestra estuvo conformada por 957 estudiantes universitarios (29.5 % varones y 70.5 % mujeres, de 13 universidades (públicas 22.36 % y privadas 77.64 %) de Lima Metropolitana. Se utilizaron la Escala de Bienestar Espiritual (SWBS), la Escala de Disposición al Perdón (TFS), la Escala de Gratitud (EG) y la Escala Breve de Resiliencia (EBR). Entre los hallazgos se encontró que el modelo estimado con el método DWLS permite señalar que el bienestar espiritual tiene efectos directos sobre el perdón, la gratitud y la resiliencia. A su vez, la covarianza entre perdón y gratitud fue .090 (p > .05), entre perdón y resiliencia de .236 (p < .01), y entre gratitud y resiliencia fue igual a .122 (p < .01). Se discuten las implicancias de los resultados.

Palabras clave: bienestar espiritual; perdón; gratitud; resiliencia; universitarios; psicología positiva

O objetivo deste estudo foi determinar a influência do bem-estar espiritual na gratidão, perdão e resiliência em estudantes universitários da cidade de Lima. Foi utilizado um desenho explicativo com variáveis latentes. A amostra foi composta por 957 estudantes universitários (29,5 % homens e 70,5 % mulheres) de 13 universidades (22,36 % públicas e 77,64 % privadas) de Lima Metropolitana. Foram utilizadas a Escala de Bem-Estar Espiritual (SWBS), a Escala de Disposição ao Perdão (TFS), a Escala de Gratidão (EG) e a Escala Breve de Resiliência (EBR). Entre os achados, encontrou-se que o modelo estimado com o método DWLS permite indicar que o bem-estar espiritual tem efeitos diretos sobre o perdão, gratidão e resiliência. Por sua vez, a covariância entre perdão e gratidão foi de .090 (p > .05), entre perdão e resiliência de .236 (p < .01) e entre gratidão e resiliência foi igual a .122 (p < .01). As implicações dos resultados foram discutidas.

Palavras-chave: bem-estar espiritual; perdão; gratidão; resiliência; universitários; psicologia positiva

Spiritual well-being is included within the framework of positive psychology that started to develop in the last decade of the last century (Snyder et al., 2016). Positive psychology was introduced by Seligman (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) with the purpose of changing the traditional paradigm (Córdova Flores et al., 2023) guiding it toward the development of qualities (Jin et al., 2021) and leaving aside the concern for the negative aspects of life. Thus, it studies flow, hope, values, well-being, optimism, happiness, resilience, positive emotions, and strengths (López & Snyder, 2009), gratitude (Moyano, 2010), and forgiveness (López et al., 2003), which is why it has acquired great relevance both for happiness and for the mental well-being of people in general (Córdova Flores et al., 2023).

Paloutzian and Ellison (1979) state that spiritual well-being is made up of religious well-being-which refers to a person's relationship with God-and existential well-being-related to meaning and purpose in life. Although distinct, they are mutually dependent; moreover, spiritual well-being is a manifestation of spiritual health and should be viewed as a continuous variable (Ellison, 1983). Spiritual well-being can be organized based on folk beliefs and embodies hope for a life based on one's relationship with oneself, the people around, nature, God and religious practices (Baykal, 2020; Ellison, 1983), life, and the future (Tudder et al., 2017).

Spiritual well-being is a holistic factor that predicts adequate mental health, with a direct and positive relationship with subjective well-being, a core that connects physical, emotional, and social aspects (Khamida et al., 2023; Yoo et al., 2022). Spiritual well-being is determinant for coping with difficult situations and having a purpose in life (Noer, 2023), it is related to resilience (Duran et al., 2020; Razaghpoor et al., 2021), hope (Dadfar et al., 2021), self-esteem and self-efficacy (Darvishi et al., 2020), adaptation to illness (Senmar et al., 2020), as well as satisfaction and joy of life (Leung & Pong, 2021). In addition, people with a good level of spiritual well-being exhibit mercy, humility, peace, honesty, and harmony (Pong, 2018), and gratitude (Tudder et al., 2017), themes studied by positive psychology. In turn, it is inversely related to anxiety and stress (Leung & Pong, 2021).

To the extent that spiritual well-being constitutes a protective factor that could positively influence several variables related to positive psychology, this study aims to explain the influence of spiritual well-being on forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience in university students.

First, forgiveness constitutes a process that favors the psychological well-being of people, provides restoration, and facilitates relationships with others (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015). It is an internal experience that involves positive cognitive and affective changes following the experience of having lived some significant loss (Thompson et al., 2005). It possesses prosocial consequences as it allows remediating those social relationships that have been deteriorated by transgressions (Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2016). For Berry et al. (2005), forgiveness constitutes a personality trait that provides favorable results for the person itself and his or her social relationships. The experience of forgiving and being forgiven is associated with the belief in some deity (Silva Chanta et al., 2023), which is directly linked to the religious component of spiritual well-being. In addition, it can be developed as a strategy for the prevention of interpersonal conflicts (García-Martín & Calero-García, 2019; Vitz, 2018), to the extent that it opens up the willingness for the reconstruction of interpersonal relationships. It has been found that college students with a greater orientation to interpersonal forgiveness present a lower tendency toward revenge after having experienced an interpersonal transgression (Rey & Extremera, 2016; Zhuang & Qiao, 2018). Regarding the relationship of forgiveness with spiritual well-being, Lawler-Row and Piferi (2006) found that people who had higher levels of forgiveness scored higher on social support, healthy behaviors, and spiritual well-being.

In a similar vein, gratitude is a construct of spiritual awareness that involves recognizing the benefits of life and appreciating the positive (Büssing et al., 2018; Manala, 2018). It constitutes a form of emotion that can subsequently become configured into an attitude or a feeling (Khairul et al., 2022). It is considered as a response of affective character caused by having received some benefit generating a prosocial behavior with the benefactor-which makes it possible to forge positive emotions such as joy and happiness, based on a cognitive processing that assigns value to the action of help received (Alarcón, 2014)-although some authors argue that people might feel gratitude for the tragedy and its consequent negative outcomes (Emmons, 2013; Jans-Beken, 2019). In general terms, it is considered as an inherent disposition of the person (Wood et al., 2010), which contributes to optimism, positive affect and satisfaction with life (McCullough et al., 2002; Portocarrero et al., 2020), and is associated with low levels of depressive symptoms (Iodice et al., 2021).

In turn, gratitude has implications in social functioning; that is, in the generation of community well-being (Lambert et al., 2010; Snyder & López, 2002), since it has been considered as an interpersonal virtue that makes possible a better bonding with others (Algoe et al., 2010), generating prosocial behaviors (Grant & Gino, 2010). Likewise, people who score high in gratitude tend to be more religious, spiritually oriented, and sensitive (McCullough et al., 2002).

Tudder et al. (2017) demonstrated that spiritual well-being constitutes a predictor of gratitude independently of personality effects in undergraduate students. Thus, to the extent that spiritual well-being constitutes both religious well-being and existential well-being (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1979), it facilitates the generation of gratitude, understood as the set of positive effects that include positive emotions (Chopik et al., 2019; McCullough, et al., 2002), a state that positively impacts the mental and spiritual health of individuals. Emmons and Kneezel (2005) found that emotions and tendencies of gratitude were related to both conventional religious practices (e.g., attending church and reading the Bible), spiritual self-transcendence and sanctification through personal goals (the perceived degree to which efforts enable one to feel closer to God), i.e., religious well-being (a component of spiritual well-being) is linked to gratitude.

Regarding resilience, currently there is no agreement in the scientific literature on the definition of that term as it includes biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors that are present at the time of response against stress (Masten et al., 2021). Some studies assume that it is a unidimensional construct, and others approach it multidimensionally (Surzykiewicz et al., 2019). In general, it is defined as the ability to recover from adverse circumstances and constitutes a protective factor against stress that allows recovery from vital situations (Ponce-Peñaloza et al., 2023; Rodríguez Ugalde, 2023; Turner, 2014).

Resilience constitutes a dynamic and adaptive process that involves the generation of internal and external resources when the person faces adverse situations and, in response, adapts and recovers quickly (Reyes-Díaz et al., 2023; Wagnild & Young, 1993). Greater stress generates greater commitment and resilience, which facilitates adaptation and emotional stability (Reyes-Díaz et al., 2023). It is the result of interactions among individuals and tangible resources in his or her environment, such as family support, friendships, schools, and services in the local community (Ahern, 2006), and varies based on gender, age, culture, and stressful situation (Seperak-Viera et al., 2023).

Regarding the relationship between spiritual well-being and resilience, it has been found that a higher level of spiritual well-being increases the level of resilience making it easier for people to cope with their problems (Eksi et al., 2019). Similar findings were obtained by Kamya (2000) in social work students. In addition, Seperak-Viera et al. (2023) report that resilience facilitates both biopsychosocial and spiritual readjustment, which promotes psychological well-being and academic performance in university students.

In other samples, a relationship has also been found between spiritual well-being, resilience, and other constructs. For example, in older adults, spiritual well-being has been directly related to resilience and inversely related to depression (Zafari et al., 2023); similar findings have been observed in patients undergoing hemodialysis (Duran et al., 2020) and those with severe medical illness (Bagereka et al., 2023).

Despite the importance of spiritual well-being in forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience, no reports have been found either in Peru or in Latin America that address them jointly. Therefore, this study aims to fill a gap and pave the way for future research. In addition, the findings are intended to allow for the development of a profile in the future with which to identify and promote individual and collective human strengths in society (Diener et al., 2018; Shoshani & Shwartz, 2018).

Method

Participants

This is an explanatory design study with latent variables (Ato García & Vallejo Seco, 2015). A non-probabilistic purposive sampling was used, and the sample consisted of 957 Peruvian university students, 29.5% males and 70.5% females, who indicated a minimum age of 16 years and a maximum age of 30 years (M males = 22.44; SD males = 3.15; M females = 21.04; SD females = 3.16), from 13 universities (4 public (22.36 %) and 9 private (77.64 %)), located in Metropolitan Lima. 31.24 % indicated being a practicing believer of some religion, 49.22 % indicated being a non-practicing believer, 3.55 % indicated being atheist, and 15.99 % reported being agnostic. Participation was voluntary and without incentives. Inclusion criteria specified participants must be Peruvian and under 30 years of age.

Instruments

Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS). It was designed by Paloutzian and Ellison (1982) to measure spiritual well-being. It comprises 20 items distributed in two dimensions: the religious well-being dimension describes the sense of satisfaction and positive connection with God (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19) and the second dimension of existential well-being refers to satisfaction with life and its purpose (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20). The items present a 6-point Likert-type response scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). It has a set of positively worded items (3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19, and 20); while there are other items worded in a negative direction (1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 16, and 18). To obtain the total score, first the items with a negative direction are inverted and then the scores of the two dimensions are added together. For this study, the adaptation by Salgado-Lévano et al. (in press) was employed, corroborating the existence of a general factor and two specific factors with adequate reliability.

Trait Forgivingness Scale (TFS). It was constructed by Berry et al. (2005) and consists of 10 items that allow the person to self-evaluate his or her propensity to forgive interpersonal transgressions. Its rating is based on a 5-point scale (from 1 “totally disagree” to 5 “totally agree”, with 10 as the minimum score and 50 as the maximum; the higher the score, the greater the willingness to forgive). Items 1, 3, 6, 7, and 8 are scored inversely, after which the total score is obtained. In this study, we used the version adapted by Los Arcos (2019) who found the internal structure by means of an exploratory factor analysis with the principal component method, and the reliability by internal consistency (α = .70).

Gratitude Scale (GS). It was developed by Alarcón (2014) and it contains three dimensions which are reciprocity (8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17), moral obligation (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 18), and sentimental quality (6 and 11), which make a total of 18 items. The items present a five-alternative Likert-type response scale, ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1), where high scores indicate positive reactions to gratitude. Items 5, 6, and 11 are inversely scored. In this research, the validation conducted by Ventura-León et al. (2018) in a sample of university students from Lima in which it is proposed that this measure presents a two-dimensional structure with a general factor, eliminating the sentimental quality dimension; this structure was verified by means of a bifactor model with a robust estimator (SB χ²/df = 0.88; SRMR=0.036; CFI=1, RMSEA=.000(.000-.017)). Scale reliability was determined by internal consistency (overall ω = .808), reciprocity (ω = .628), and moral obligation (ω = .767).

Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). Originally designed by Wagnild (2009), it measures the degree of individual resilience, understood as a positive personal characteristic that facilitates adaptation to situations of adversity. It is composed of 14 items with a Likert scale with options ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). This study used the Spanish adaptation of Sánchez-Teruel and Robles-Bello (2015) who applied an exploratory factor analysis to corroborate the internal structure, finding a unidimensional structure that explains 75.97% of the variance. They also found that the BRS is indirectly related to the STAI (anxiety) and BDI (depression) scores. Reliability was found for internal consistency, obtaining α = .79.

Procedures

The research team was directly responsible for coordinating with the educational institutions. The administration of the instruments was online, for which a Google Forms form was prepared containing the informed consent, a socio-educational data sheet, and the protocols of the four instruments. For greater rigor in the application, we followed (1) the guidelines established by the American Educational Research Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education (2018) for both the security and confidentiality of the information, (2) the norms established in Chapter III, Research of the Ethics and Deontology Code of the College of Psychologists of Peru (2017), and (3) the criteria proposed by Elosua (2021), to reduce the effects that the virtual application could have. Only those who agreed to participate in the research and marked in the affirmative in the informed consent were part of the sample.

Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS software version 25 and RStudio version 1.1.456, specifically with the lavaan library (Rosseel et al., 2018). Initially, the exploratory analysis was performed to identify outliers and missing data; in the case that their presence does not exceed 5%, it was considered pertinent to apply a missing data imputation procedure.

The descriptive analysis included the mean (M), standard deviation (SD), minimum (Min) and maximum (Max) scores, skewness coefficient (g1) and kurtosis (g2). For the identification of the relationships between the variables, the correlation matrix was reported; for its interpretation, Cohen's (1992) suggestions were taken, where values equal to or lower than .10 are considered as null effect, those greater than .10 up to .30 are small effect, those greater than .30 up to .50 are medium effect, and values greater than .50 are large effect.

Structural equation analysis using the Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance Adjusted (WLSMV) method was used to perform the model, due to the categorical nature of the variables (Verdam et al., 2016). The measurement model includes the relationships of the items with each of their constructs and the relationships between the latent variables are reported. The structural model fit was explored using the chi-square ratio between degrees of freedom (χ2 /df) with expected values below 3, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) in both cases values below .08 are expected (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of Jöreskog and Sörbom (1986) was also reported whose acceptable values were above .95 (Bentler, 1992; Hair et al., 2010), as was the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) (Kline, 2015).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 shows the descriptive measures indicating the tendency of the averages towards the maximum scores. However, in the case of spiritual well-being, a coefficient of variation equal to 21.6% is obtained, which suggests homogeneity in the scores. With respect to forgiveness, this reaches a coefficient of variation equal to 19.9%, which corresponds to the same category. In the case of the gratitude scores, the variation is equal to 14.1%, which means that the data are very homogeneous, as are the Resilience scores, which obtained a coefficient equal to 17.4%. Regarding the skewness and kurtosis coefficients, asymmetries with a negative tendency can be observed in all cases. In relation to kurtosis, the values suggest predominantly leptokurtic tendencies.

Structural Equation Modeling

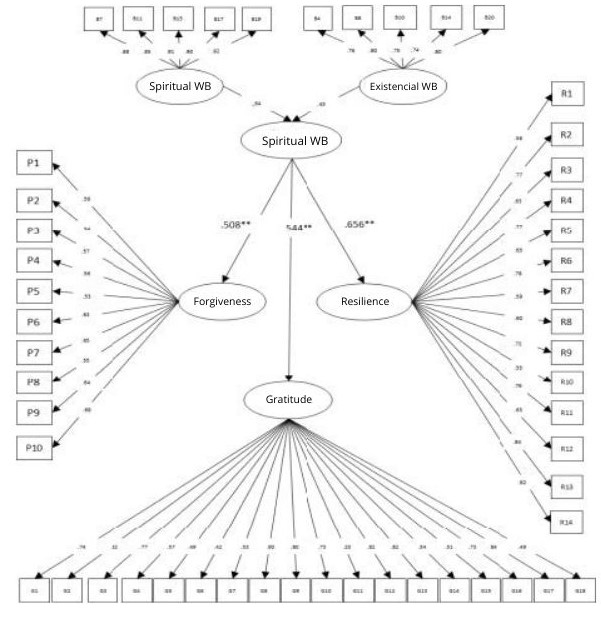

The model was estimated with the DWLS method, and to verify its relevance, the following fit indices were reviewed: CFI = .966, TLI = .964, RMSEA = .079 (.078-.081), SRMR = .070, all of them with adequate values. The analysis of the measurement models for each of the instruments was adequate with factor loadings above .40 in all cases, except for item 11 of the Gratitude Scale. Regarding the relationship between the variables, it can be observed that spiritual well-being has direct effects on forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience (see Figure 1). Likewise, the covariance between forgiveness and gratitude was .090 (p > .05), while the covariance between forgiveness and resilience was .236 (p < .01), and the covariance between gratitude and resilience was equal to .122 (p < .01).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify the extent to which spiritual well-being explains forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience in a sample of university students in Lima. The results show that these relationships are fulfilled; it was found that spiritual well-being has direct, statistically significant, and moderate effects on forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience. In this regard, the analysis of the descriptive measures shows averages with a tendency towards maximum scores, which suggests a strong presence of spiritual well-being, disposition to forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience. By verifying the homogeneity of the data, we understand that the variations of these scores are not meaningful beyond the different sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. In this sense, the tendency of young people to present positive orientations toward positive psychological attributes is similar to that reported by Razaghpoor et al. (2021), Baykal (2020), and Duran et al. (2020). This is important for the quality of life of university students, given that the spiritual component has been identified as highly valued by them (Grimaldo et al., 2020; López-Sánchez et al., 2023).

The results are consistent with the findings of Vitz (2018) in pointing out that the factors that contribute to the willingness to forgive and rebuild social and interpersonal relationships that have been damaged by transgressions are associated with the search for inner peace and greater awareness of shared humility; both elements of spiritual well-being (Ellison, 1983). Along the same line, Zhuang and Qiao (2018) found that forgiveness is built from a framework of values and principles that foster understanding, empathy, and acceptance, which would correspond to the dimension of existential well-being, within spiritual well-being, related to meaning and purpose in life (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1979).

The findings of the present study would indicate that dynamic processes involving cognitive, functional, and emotional domains of spiritual well-being positively affect both the internal disposition and social interactions of a person (Chou et al., 2016), being the essential elements for forgiveness from a prosocial stance spoken of by Bartholomaeus and Strelan (2016) an important route to contribute in harmony, restoration, and relationship with others (Rey & Extremera, 2016; Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015). In addition, it is established from the basis of positive cognitive and affective changes where forgiveness is structured, after the experience of having experienced a significant loss or transgression (Thompson et al., 2005).

Previous studies have found that forgiveness requires emotional regulation to cope with conflict and employ the ability to empathize with others' perspectives and the recognition that people are complex integrations of positive and negative (Lawler-Row & Piferi, 2006). Accordingly, spiritual well-being provides human beings with positive attitudes, sense of satisfaction, enjoyment, and harmony that favor emotional regulation and favorable attitudes toward social interaction (Ataei & Chorami, 2021; Yoo, 2023). Thus, spiritual well-being favors and promotes the generation of positive aspects such as optimism, self-efficacy, social capacity, and emotional support that benefit the process of forgiveness evidenced in this study.

In relation to the effects of spiritual well-being on gratitude, the findings coincide with the study of Khairul et al. (2022) who point out that spiritual well-being is one of the main factors that influence gratitude, that form of emotion or feeling that later becomes an attitude. Likewise, similarity is found with the reports of Chopik et al. (2019) when specifying that that set of positive effects and emotions are structured on the basis of processes linked to the meaning and purpose in life, and that related to the divine, which would correspond to the existential and religious dimensions of spiritual well-being (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1979).

Various studies such as those of Leung and Pong (2021) and Manala (2018) point out that gratitude implies recognizing the benefits of life and appreciating the positive, generating affections and positive emotions, which correspond mostly with the purpose of life that makes up spiritual well-being. On the other hand, the sense of life gives the individual the possibility of facing difficult situations that conclude in a sense of gratitude (Emmons, 2013). Previous studies have already found that the dimension of religious well-being is associated with people with high levels of gratitude with more religious and spiritually sensitive orientations (McCullough et al., 2002).

Concurring with Eksi et al. (2019), spiritual well-being fosters growth in love, enjoyment for life and peace through the pursuit of a fulfilling life and contribution to others to help them improve their own spiritual health, which is the basis for generating gratitude and assigning value to the action of help received (Alarcón, 2014). This also has implications for generating community well-being and bonding with others (Algoe et al., 2010; Lambert et al., 2010).

On the other hand, the findings of this study show a positive and direct effect on resilience. Similar results were found in the studies of Razaghpoor et al. (2021), Baykal (2020), and Duran et al. (2020), who state that spiritual well-being provides a person with pillars such as connection, meaning, and purpose in life, which in turn generate hope, a sense of belonging and adaptation, all of which are basic elements for the structure of resilience. A strong sense of spiritual well-being helps people cope more effectively with adversity, providing them with strategies to cope with and overcome the challenges they face (Turner, 2014).

Other studies have reported that a higher level of spiritual well-being favors the development of resilience by facilitating the generation of resources to face adversity and, in response, adapt and recover quickly (Eksi et al., 2019). In addition, among the best predictors of greater resilience are having a purpose in life, a sense of well-being about the future, and the ability to appreciate life (Noer, 2023).

This study adds to the current literature by demonstrating the influence of spiritual well-being on forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience, with evidence based on conceptualization and practice. These findings have implications in the field of social and health sciences to raise the levels of spiritual well-being, gratitude, forgiveness, and resilience, and related constructs, even more so, as Córdova Flores et al. (2023) point out, in university contexts that are characterized by not promoting them.

In education, its importance lies in the fact that leveraging potentialities and emphasizing these types of constructs, greater personal and academic growth can be achieved, thus contributing to integral well-being (Córdova Flores et al., 2023), a task in which the family, educational institutions, and the social environment intervene (Rodríguez Ugalde, 2023). Health professionals and policy makers can use these findings for measurement, prevention, and strengthening objectives that impact on mental health, generating spaces for intervention and awareness that favor the integral development of students and people in general.

However, this study has some limitations. The use of a purposive sample means that the findings cannot be generalized (Reales Chacón et al., 2022; Otzen & Manterola, 2017). Additionally, the study only includes university students from Lima, which restricts the generalizability of the results. There is also confusion at the epistemological level regarding the concept of spiritual well-being, which is often mistaken for terms such as spirituality, spiritual health, and religiosity, despite arousing great interest in the scientific community. It is important for future research to be more rigorous in defining and presenting these constructs in the scientific literature. Furthermore, the self-report nature of the instruments used in the study introduces subjectivity in the responses due to potential social desirability (Louzán Mariño, 2020; Navarro-González et al., 2016).

Future studies are crucial to explore diverse sociocultural contexts in different cities and regions using longitudinal or experimental designs and quantitative and qualitative measures. Further research is essential to explore the influence of spiritual well-being in diverse populations, considering sociodemographic variables such as gender, religious affiliation, educational level, and marital status, among others.

REFERENCES

Ahern, N. R. (2006). Adolescent resilience: an evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 21, 175-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2005.07.009 [ Links ]

Alarcón, R. (2014). Construcción y valores psicométricos de una Escala para medir la Gratitud. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 4(2), 1520-1534. [ Links ]

Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It’s the little things: everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x [ Links ]

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2018). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. American Educational Research Association. [ Links ]

Ataei, Z., & Chorami, M. (2021). Predicting academic emotions based on spiritual well-being and life satisfaction in students of shahrekord girls’ technical and vocational school. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1250 [ Links ]

Ato García, M., & Vallejo Seco, G. (2015). Diseños de investigación en Psicología. Pirámide. [ Links ]

Bagereka, P, Ameli, R, Sinaii, N, Vocci, M. C., & Berger, A. (2023). Psychosocial-spiritual well-being is related to resilience and mindfulness in patients with severe and/or life-limiting medical illness. BMC Palliative Care, 22(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01258-6 [ Links ]

Bartholomaeus, J., & Strelan, P. (2016). Just world beliefs and forgiveness: The mediating role of implicit theories of relationships, Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 106-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.081 [ Links ]

Baykal, E. (2020). Boosting resilience through spiritual well-being: COVID-19 example. Bussecon Review of Social Sciences, 2(4), 18-25. https://doi.org/10.36096/brss.v2i4.224 [ Links ]

Bentler, P. M. (1992). On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 400-404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.400 [ Links ]

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588-606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588 [ Links ]

Berry, J. W., Worthington, E. L., O'Connor, L. E., Parrot, L., & Wade, N. G. (2005). Forgiveness, vengeful rumination and affective traits. Journal of Personality, 73(1), 183-226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00308.x [ Links ]

Büssing, A., Recchia, D. R., & Dienberg, T. (2018). Attitudes and behaviors related to Franciscan-inspired spirituality and their associations with compassion and altruism in Franciscan brothers and sisters. Religions, 9(10), 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100324 [ Links ]

Chopik, W. J., Newton, N. J., Ryan, L. H., Kashdan, T. B., & Jarden, A. J. (2019). Gratitude across the life span: age differences and links to subjective well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(3), 292-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1414296 [ Links ]

Chou, M. J., Tsai, S. S., Hsu, H. M., & Ho-Tang, W. (2016). Research on correlation between the life attitude and wellbeing-with spiritual health as the mediator. European Journal of Social Sciences, 4, 76-88. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1992). Una imprimación poderosa. Boletín Psicológico, 112(1), 155-159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [ Links ]

Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú. (2017). Código de Ética y Deontología. [ Links ]

Córdova Flores, E. C., Vilela Ordinola, E. A., Salazar Avalos, M. M., Salazar Llerena, S. L., & Márquez Tirado, V. S. D. (2023). La Psicología positiva y la autoconfianza o autoconcepto de los estudiantes universitarios: Revisión sistemática de la literatura. Revista de la Universidad del Zulia, 40, 440-464. https://doi.org/10.46925//rdluz.40.25 [ Links ]

Dadfar, M., Lester, D., Turan, Y., Beshai, J. A., & Human-Friedrich, U. (2021) Religious spiritual well-being: results from Muslim Iranian clinical and non-clinical samples by age, sex and group. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 33(1), 16-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2020.1818161 [ Links ]

Darvishi, A., Otaghi, M., & Mami, S. (2020). The effectiveness of spiritual therapy on spiritual well-being, self-esteem and self-efficacy in patients on hemodialysis. Journal of Religion and Health, 59, 277-288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-00750-1 [ Links ]

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2018). Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.115 [ Links ]

Duran, S., Avci, D., & Esim, F. (2020). Association between spiritual well-being and resilience among Turkish hemodialysis patients. Journal of Religion and Health, 59, 3097-3109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01000-z [ Links ]

Eksi, H., Boyali, C., & Ummet, D. (2019). Predictive role of spiritual well-being and meaning in life on psychological hardiness levels of teacher candidates: A testing structural equation modelling (SEM). Kastamonu Education Journal, 27(4), 1695. https://doi.org/10.24106/kefdergi.3256 [ Links ]

Ellison, C. W. (1983). Spiritual well-being: conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 11(4), 330-340. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164718301100406 [ Links ]

Elosua, P. (2021). Aplicación remota de test: riesgos y recomendaciones. Papeles del Psicólogo, 42(1), 33-37. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2021.2952 [ Links ]

Emmons, R. A. (2013). How gratitude can help you through hard times. Greater Good Science Center, 13. [ Links ]

Emmons, R. A., & Kneezel, T. T. (2005). Giving thanks: spiritual and religious correlates of gratitude. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 24, 140-148. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D., & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2015). Forgiveness therapy: an empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

García-Martín, M. B., & Calero-García, M. D. (2019). ESCI: Solución de conflictos interpersonales: Cuestionario y programa de intervención. Manual Moderno. [ Links ]

Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 946-955. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0017935 [ Links ]

Grimaldo, M. P., Correa Rojas, J. D., Jara Sánchez, D., Cirilo Acero, I. B., & Aguirre Morales, M. T. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Calidad de vida de Olson y Barnes en estudiantes limeños (ECVOB). Health and Addictions/Salud Y Drogas, 20(2), 145-156. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v20i2.545 [ Links ]

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (2010). Análisis multivariante. Pearson. [ Links ]

Iodice, J.A., Malouff, J.M., & Schutte, N.S. (2021). The association between gratitude and depression: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Depression and Anxiety 4(1), 1-12. https://doi.org//10.23937/2643-4059/1710024 [ Links ]

Jans-Beken, L. (2019). Een zoektocht naar dankbaarheid. Uitgeverij JansBeken. [ Links ]

Jin, Y., Dewaele, J., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2021). Reducing anxiety in the foreign language classroom: A positive psychology approach, System, 101, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102604. [ Links ]

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1986). Lisrel VI: Analysis of Linear Structural Relationships by Maximum Likelihood and Least Square Methods. Scientific Software, Inc. [ Links ]

Kamya, H. A. (2000). Hardiness and spiritual well-being among social work students: Implications for social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(2), 231-240. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2000.10779004 [ Links ]

Khairul, H., Nurmalasari, E., Annisa, O., Hidayat, T., Fitriyani, N., & Pernanda, S. (2022). The influenced factors of gratitude: a systematic review. Proceeding of International Conference on Islamic Guidance and Counseling, 2, 9-16. [ Links ]

Khamida, Y. A., Fitryasari, R., Hasina, S. N., & Putri, R. A. T. (2023). The relationship of spiritual well-being with subjective well-being students in Islamic boarding school. Malaysian Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences, 19, 93-98. [ Links ]

Kline, R. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (4a ed.). The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Lambert, N. M., Clark, M. S., Durtschi, J., Fincham, F. D., & Graham, S. M. (2010). Benefits of expressing gratitude: Expressing gratitude to a partner changes one’s view of the relationship. Psychological Science, 21(4), 574-580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610364003 [ Links ]

Lawler-Row, K. A., & Piferi, R. L. (2006). The forgiving personality: describing a life well lived? Personality and Individual Differences, 41(6), 1009-1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.007 [ Links ]

Leung, C. H., & Pong, H. K, (2021). Cross-sectional study of the relationship between the spiritual wellbeing and psychological health among university Students, Plos One, 16(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249702 [ Links ]

López, S. J., & Snyder, C. R. (2009). The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

López, S. J., Snyder, C. R., & Rasmussen, H. N. (2003). Striking a vital balance: Developing a complementary focus on human weakness and strength through positive psychological assessment. En S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.). Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 3-20). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10612-001 [ Links ]

López-Sánchez, O., Cortijo-Palacios, X., Sandoval-Guzmán, P. E., González-Carrada, E., & Robles-Mendoza, A. L. (2023). Socio-emotional processes during the COVID 19 pandemic in graduate students. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria (Digital Journal of University Teaching Research), 17(1), e1689. https://doi.org/10.19083/ridu.2023.1689 [ Links ]

Los Arcos, A. (2019). Amabilidad y perdón: El papel mediador de la condicionalidad del perdón. (Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Pontificia Comillas). Repositorio Comillas: https://repositorio.comillas.edu/xmlui/handle/11531/52889 [ Links ]

Louzán Mariño, R. (2020). Mejorar la calidad de las evaluaciones de riesgos psicosociales mediante el control de sesgos. Archivos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales, 23(1), 68-81. https://doi.org/10.12961/abril.2020.23.01.06 [ Links ]

Manala, M. J. (2018). Gratitude as a Christian lifestyle: an Afro-reformed theological perspective. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, 74(4). https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i4.5117 [ Links ]

Masten, A. S., Lucke, C. M., Nelson, K. M., & Stallworthy, I. C. (2021). Resilience in development and psychopathology: multisystem perspectives. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17, 521-549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-120307 [ Links ]

McCullough, M. F., Emmons, R. R., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112-127. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112 [ Links ]

Moyano, N. (2010). Gratitud en la Psicología Positiva. Psicodebate, 10, 103-118. https://doi.org/10.18682/pd.v10i0.391 [ Links ]

Navarro-González, D., Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2016). How response bias affects the factorial structure of personality self-reports. Psicothema, 28(4), 465-470. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.113 [ Links ]

Noer, M. (2023). Spiritual well-being and mental health illness among students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Indonesia. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 7(2), 63-83. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v7i2.271 [ Links ]

Otzen, T., & Manterola C. (2017). Técnicas de muestreo sobre una población a estudio. International Journal of Morphology, 35(1), 227-232. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0717-95022017000100037 [ Links ]

Paloutzian, R. F., & Ellison, C. W. (1979). Religious commitment, loneliness, and quality of life. CAPS Bulletin, 5(3). [ Links ]

Paloutzian, R. F., & Ellison, C. W. (1982). Loneliness, spiritual well-being and the quality of life. En L. A. Peplau, & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy (pp. 224-236). John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Ponce-Peñaloza, A. P., Calcina-Cuevas, S. C., Martínez-García, A. J., & Vilca-Miranda, A. (2023). Resiliencia de estudiantes universitarios postpandemia de la COVID-19. Polo del Conocimiento, 8(3), 2145-2154. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v8i3 [ Links ]

Pong, H. K. (2018). Contributions of religious beliefs on the development of university students’ spiritual well-being. International Journal of Children's Spirituality, 23(4), 429-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364436X.2018.1502164 [ Links ]

Portocarrero, F. F., Gonzalez, K., & Ekema-Agbaw, M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110101 [ Links ]

Razaghpoor, A., Rafiei, H., Taqavi, F., & Hashemi, M. (2021). Resilience and its relationship with spiritual wellbeing among patients with heart failure. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing, 16(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2020.0109 [ Links ]

Reales Chacón, L J., Robalino Morales, G. E., Peñafiel Luna, A. C., Cárdenas Medina, J. H., Cantuña-Vallejo, P. F. (2022). El Muestreo intencional no probabilístico como herramienta de la investigación científica en carreras de Ciencias de la Salud. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 14(S5), 681-691. [ Links ]

Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2016). Agreeableness and interpersonal forgiveness in young adults: the moderating role of gender. Terapia Psicológica, 34(2), 103-110. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082016000200003 [ Links ]

Reyes-Díaz, J. I., Arizmendi-Cotero, D., Velázquez-Garduño, G., & Rivera-Ramírez, F. (2023). Compromiso y resiliencia en estudiantes universitarios postpandemia de COVID-19. Revista de Investigación Educativa RedCA, 6(17), 48-69. [ Links ]

Rodríguez Ugalde, E. (2023). Estrategias de resiliencia en ambientes familiares y educativas durante la pandemia. Revista ConCiencia EPG, 8(Especial), 23-35. https://doi.org/10.32654/ConCiencia/eds.especial-2 [ Links ]

Rosseel, Y., Oberski, D., Byrnes, J., Vanbrabant, L., Savalei, V., Merkle, E., & Jorgensen, T. D. (2018). Package ‘lavaan’ 0.6-3. https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/lavaan/lavaan.pdf [ Links ]

Salgado-Lévano, C., Correa-Rojas, J., & Mori-Sánchez, M. (en prensa). Psychometric evidence of the Spiritual Well-being Scale in university students from Lima. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Teruel, D., & Robles-Bello, M. A. (2015). Escala de Resiliencia 14 ítems (RS-14): Propiedades Psicométricas de la versión en español. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación - e Avaliação Psicológica, 2(40), 103-113. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 [ Links ]

Senmar, M., Hasannia, E., Moeinoddin, A., Lotfi, S., Hamedi, F., Habibi, M., Noorian, S., & Rafiei, H. (2020). Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness and Its Relationship with Spiritual Wellbeing in Iranian Cancer Patients. International Journal of Chronic Diseases, 5742569. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5742569 [ Links ]

Seperak-Viera, R., Torres-Villalobos, G., Gravini-Donado, M., & Domínguez-Lara, S. A. (2023). Invarianza factorial de dos versiones breves de la Escala de Resiliencia de Connor-Davidson (cd-risc) en estudiantes universitarios de Arequipa. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 26(1), 95-112. https://doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2023.26.1.7 [ Links ]

Shoshani, A., & Shwartz, L. (2018). From character strengths to children’s well-being: development and validation of the Character Strengths Inventory for Elementary School Children. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02123 [ Links ]

Silva Chanta, S. T., Camacho Huapaya, R. M., & Casas Miranda, R. J. M. (2023). El perdón en la convivencia escolar. Horizontes. Revista de Investigación en Ciencias de la Educación, 7(30), 1863-1876. https://doi.org/10.33996/revistahorizontes.v7i30.635 [ Links ]

Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.). (2002). The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Snyder, C. R., Lopez, S. J., Edwards, L. M., & Marques, S. C. (Eds.) (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (3a ed. ). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199396511.001.0001 [ Links ]

Surzykiewicz, J., Konaszewski, K., & Wagnild, G. (2019). Polish version of the Resilience Scale (RS-14): a validity and reliability study in three samples. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02762 [ Links ]

Thompson, L. Y., Snyder, C. R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S. T., Rasmussen, H. N., Billings, L. S., Heinze, L., Neufeld, J. E., Shorey, H. S., Roberts, J. C., & Roberts, D. E. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Personality, 73(2), 313-59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00311.x [ Links ]

Tudder, A., Buettner, K., & Brelsford, G. M. (2017). Spiritual well-being and gratitude: The role of positive affect and affect intensity. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 36(2), 121. [ Links ]

Turner, S. (2014). The resilient nurse: an emerging concept. Nurse Leader, 12(6), 71-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2014.03.013 [ Links ]

Ventura-León, J., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., & Barboza-Palomino, M. (2018). Análisis psicométrico preliminar de una medida de gratitud en estudiantes universitarios de Lima. Revista de Psicología, 8(2), 13-31. [ Links ]

Verdam, M. G., Oort, F. J., & Sprangers, M. A. (2016). Using structural equation modeling to detect response shifts and true change in discrete variables: an application to the items of the SF-36. Quality of life research: an international Journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 25(6), 1361-1383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1195-0 [ Links ]

Vitz, P. C. (2018). Addressing moderate interpersonal hatred before addressing forgiveness in psychotherapy and counseling: a proposed model. Journal of Religion and Health, 57, 725-737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0574-6 [ Links ]

Wagnild, G. (2009). A review of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 17, 105-113. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.17.2.105 [ Links ]

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1, 165-178. [ Links ]

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 890-905. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005 [ Links ]

Yoo, J. (2023). The influence of spiritual well-being on depression among protestant college seminarians in Korea with a focus on the mediating effect of self-esteem. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 51(1), 122-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091647122111860 [ Links ]

Yoo, J., You, S., & Lee, J. (2022). Relationship between neuroticism, spiritual well-being, and subjective well-being in Korean university students. Religions, 13(6), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060505 [ Links ]

Zafari, M., Sadeghipour Roudsari, M., Yarmohammadi, S., Jahangirimehr, A., & Marashi, T. (2023). Investigating the relationship between spiritual well-being, resilience, and depression: a cross-sectional study of the elderly. Psychogeriatrics, 23(3), 442-449. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12952 [ Links ]

Zhuang, Z. Y., & Qiao, W. (2018). A study on college students’ psychology of revenge and interpersonal forgiveness and the relationship with health education, EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(6), 2487-2492. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/89517 [ Links ]

How to cite: Salgado-Lévano, C., Grimaldo Muchotrigo, M., Correa-Rojas, J., Mori Sánchez, M. P., & Riveros Paredes, P. (2024). Spiritual well-being and its influence on forgiveness, gratitude, and resilience in university students in Lima (Peru). Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3833. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3833

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. C. S. L. has contributed in 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14; M. G. in 1, 3, 5, 8, 13, 14; J. C. R. in 2, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14; M. M. in 1, 3, 13, 14; P. R. P. in 1, 3, 13, 14.

Received: December 28, 2023; Accepted: July 05, 2024

texto en

texto en