1. Introduction

Political financing can be seen as a market relationship with supply and demand. This analogy is not a novel concept, but it is functional. On the demand side, we can consider candidates and parties that depend on resources to be elected. The mechanisms that link one to another can be diverse. However, money is essential for, in the case of candidates, the acquisition of campaign material, payment of employees, and advertisements on social networks, among others. Therefore, we have two variables: money and votes, and some mechanisms that link both so that, on average, more expensive campaigns lead to success, even though not always. On the supply side, we have the resources that are (legally) available to parties and candidates, both at the time of elections and in day-to-day political work (Hopkin, 2004; Krause y Schaefer, 2022; Mancuso, 2015; Reis, 2020; Reis et al., 2015; Santos, 2016).

Hence, we have supply and demand. A market in which resources are in demand and have specific sources of donors. In the Brazilian case, electoral and party financing regulation changes have reacted to unexpected events or crises. Moreover, supply regulation (Krause y Schaefer, 2022; Speck, 2016a;2016b).

In this paper, we deal with the most recent data on electoral financing in Brazil, considering the regulation of supply and demand mechanisms. Mainly, we focus on the results for political representation throughout the Bolsonaro government (2019-2022), in which there were changes promoted by the Legislature (restriction of the use of self-financing of candidates) by the Judiciary (proportionality of resources destined to black-led candidacies); and by the Executive. In the latter case, we explore data that goes beyond the regulation of the Brazilian Electoral Justice and touch on the point of delivery of pork barrel (parliamentary amendments) via the so-called Secret Budget.

We selected the case of Brazil because it is a country that has recently undergone a series of changes in electoral financing legislation. These changes primarily result from a series of corruption allegations unveiled in the context of criminal investigations (Reis, 2020; Schaefer, 2022). As pointed out by the literature, whether in the case of Latin America or other contexts, scandals can serve as catalysts for institutional change (Castañeda, 2018; Fuentes, 2018; Scarrow, 2004; Witko, 2007). In this sense, the Brazilian case may be interesting to understand the dynamics of changes in the relationship between money and politics. It is also important to consider that our study does not aim to make causal inferences (why will the reforms take a specific form?) but to describe the Brazilian case and propose hypotheses that could be tested comparatively.

The data used throughout the article were taken from the Superior Electoral Court (tse) to analyze the financing of campaigns and parties and electoral results. The «secret budget» information was systematized from the data of Breno Pires, a Brazilian journalist, and the Chamber of Deputies. All data were organized and analyzed in R and are publicly available.1

To achieve these objectives, the text is organized as follows: in section two, we present our framework; in section three, we deal with Brazilian legislation and regulation of the supply of financial resources in electoral campaigns and its recent changes. In section four, we highlight the case of demand for resources. In section five, we deal with changes in funding carried out through the Judiciary; in section six, the emphasis is on resources that affect elections but are not campaign resources (as in the case of pork barrel). Finally, we make our final considerations.

2. Framework

The financing of politics, especially electoral financing, remains a perennial challenge for democracies and a central topic in political science (Zovatto, 2005). Research on political financing addresses various questions. For example, what is the effect of money on electoral outcomes? Which candidates receive the most resources from private or public donors? Does financial investment yield return for donors in terms of legislation or public policy? What regulatory models are adopted? Why do legislators change the models for financing campaigns and parties?

Recent evidence has shown that resources matter for electoral outcomes (Arraes, Amorim y Simonassi, 2017; Borba y Cervi, 2017; Jacobson, 1978; Samuels, 2001b). Candidates with political capital benefit, perpetuating the inequality of political representation (especially for racial minorities and women) (Bolognesi et al., 2020; Gatto y Wylie, 2022). Donors benefit after campaign contributions (Mancuso, 2015; Santos et al., 2015). Regarding regulatory models, there is a normative debate on how to handle the relationship between money and politics so that resources are distributed more equitably, so that money is not the sole determinant of electoral success, and there is transparency and control over potential misuse (Reis et al., 2015). More recently, the literature also identified causes of legislative changes: corruption scandals, shifts in the balance of power between new and traditional parties, and the influence of external actors (international organizations) (Borel, 2015; Freidenberg y Mendoza, 2019; Fuentes, 2018; Scarrow, 2004).

There is a trade-off in regulatory models between limiting the money in elections and ensuring the representation rights of different groups. In the latter case, the United States serves as a «free-for-all» model where the Supreme Court has ruled that campaign financing by private actors is protected as a right to «free expression». The more restrictive models, like Brazil’s, include spending caps and a ban on corporate donations. A central issue is that legislation, when restrictive, can be merely «fictional». Officially, money is limited, but in «real life», it is passed among candidates, parties, and private donors. In this sense, the electoral regulatory body’s authority, independence, and power are essential.

In this article, we do not intend to explain why Brazilian legislation has changed in recent years but to describe these changes and propose hypotheses that can be tested comparatively. We start from a model that considers financing as a relationship between demand and supply. On one hand, the country’s territorial and demographic characteristics, as well as the electoral system, make campaigns expensive (Cox y Thies, 2000; Samuels, 2001b). As the system for electing federal, state, and city councilors is an open list proportional representation, candidates compete not only with other parties but also with colleagues from their own party, increasing the pressure for resources. The most significant change in demand was the establishment of a spending cap, a measure that has proven effective in reducing campaign expenses and increasing competitiveness (Avis et al., 2022). However, comparatively, getting elected in Brazil still costs a lot of money.

On the other hand, the supply has been highly regulated in recent years in the wake of corruption scandals and changes in political competition. The prohibition of corporate donations, a decision made by the Judiciary and not the Legislature, was replaced by almost exclusively public financing (Fisch y Mesquita, 2022; Krause y Schaefer, 2022; Reis, 2020; Silva y Cervi, 2017). This reduces the influence of private actors but may signify an even greater distancing of Brazilian parties from society-a process of cartelization (Katz y Mair, 1995).

Another point to consider is that the money circulating in campaigns is not the only financial factor that guarantees electoral success. Other resources, such as pork-barrel, are attractive to candidates.

3. Brazilian legislation and supply regulation: the concentration of donations

The new Brazilian democracy had many changes in its model of political financing; however, one feature has remained relatively consistent. Regardless of changes in the rules, the supply of available resources showed a pattern of donor source concentration, whether it came from private resources, from companies and individuals, or from public resources.

Until 1993, Brazilian legislation on political financing prohibited corporate donations to parties or candidates. The scandal that followed the election of Fernando Collor de Melo led to a new law. The realization that the president’s campaign, then already removed from office, had used corporate resources to get elected was a catalyst for the Brazilian Legislative to change its understanding, allowing corporate donations (Law No. 8,713 from 1993), which had been prohibited during the Military Dictatorship. The perception at the time was that, by regularizing this type of donation, there would no longer be a «slush fund» (undeclared funds - «Caixa 2»), as donations would be legal and registered, without the need to hide them (Campos, 2009; Fisch y Mesquita, 2022; Mancuso, 2015).

From then on, there was new legislation on parties in 1995, allowing corporate donations to these organizations, and, in 1997, a law specific to elections (Law No. 9,504) that consolidated the permission for donations from corporations. New corruption scandals and allegations of unrestrained relationships between companies and candidates, parties, and governments led to the decision to return to the ban on corporate donations in 2015. The measure profoundly altered the way politics were financed in Brazil and followed a series of corruption scandals that laid bare the relationship between donors (entrepreneurs of large companies, such as in the civil construction and food sectors) and politicians of all parties.

The back-and-forth experiences with this type of donation allow us to observe that it is not merely allowing or prohibiting corporate funding that prevents the influence of business groups and economic power in politics.

From 1993 to 2015, we had on the «supply side» to parties and candidates, private resources from companies and individuals, and self-financing and public resources (through the Fundo Partidário, translated as Party Fund). This last point is the most controversial. It is good to remember that the Party Fund was created in 1971, that is, during the Military Dictatorship.

Within this scenario, the leading share of resources for elections came from companies. Moreover, it ought to be highlighted not only companies but a few specific companies. According to Mancuso (2015), 70 % of the resources used in electoral campaigns came from contributions from legal entities, with some companies from specific economic sectors being the most relevant. For example, civil construction. A scenario of a few companies donating many resources to several candidates. If we look at the accounts for presidential candidates, congressional candidates, and parties, we see that the same companies donated to all candidates and parties with a chance of winning. That is, without the criterion of a programmatic and ideological identification (Krause et al., 2015; Santos, 2016).

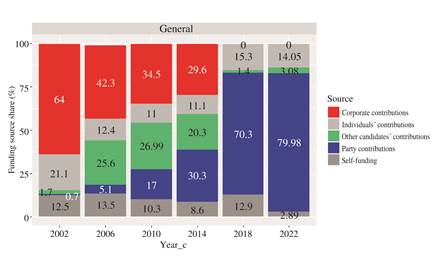

In Figure 1, we observe the evolution of the percentage of each source of funds in general elections from 2002 to 2022 (when data are available). There is a particular discrepancy in the case of companies, but this is due to the companies’ own strategies. The amounts in red, referring to corporate donations, account for direct contributions from companies to candidates. The values of party contributions and donations from other candidates, however, until 2014, should also be considered in this account, given that companies transferred the money indirectly: first to the parties and then to the candidates (Horochovski et al., 2016; Mancuso, 2015; Mancuso, Horochovski, y Camargo, 2018). This strategy aimed, on the one hand, to «hide» the contributions and, on the other hand, to generate greater subsequent coordination. This is because a company like Odebrecht (a construction company) would donate to a party at their national level, and these national leaders would choose the candidates who benefited from the money. In this way, the company guaranteed access to the politicians.

The concentration of donors is an element that weakens diversity and balance in political competition. The relationship between the supply of resources for parties and campaigns and demand from the latter can generate a series of challenges when based on some sense of reliance. For example, if there is an exchange of favors between donors and political agents (Mancuso, 2015). The theme is complex and subject to regulation around the world, and we saw here how problematic it was (Zovatto, 2005). In Brazil, the option, again, was the regulation of supply. In 2015, a decision by the Federal Supreme Court declared corporate donations to campaigns and parties unconstitutional in the wake of the Lava-Jato operation (Schaefer, 2022).

One of the effects was the reinforcement of other sources such as (a) the candidates’ own resources (self-financing), (b) individuals, but, mainly, (c) the increase of public resources for electoral campaigns. In the first case, we saw, already in the first election with a ban on corporate financing, in the 2016 municipal election, the success of self-financed millionaire candidates, such as the mayor of São Paulo João Dória (psdb). In the second, donations from businessmen who now began to transfer resources via individuals and not legal entities, and in the third, the increase in the Partisan Fund and the creation of the Special Campaign Financing Fund (fefc), respectively. It is important to highlight an element of the Brazilian electoral system that encourages individual careers: the open-list voting system for legislative positions in proportional elections. Candidates’ electoral campaigns are very individualized, and each competitor must seek their donations. This logic establishes, on the one hand, direct and close links between the candidate and his donor without his party’s control. On the other hand, it promotes entrepreneurial-style candidacies, in which the political career is predominantly a self-investment with a business logic.

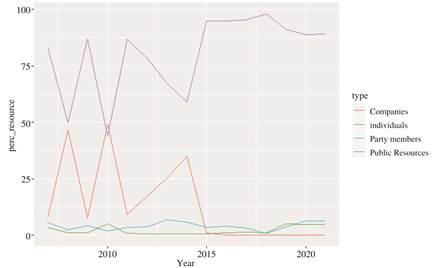

The financing model of Brazilian politics continues to be mixed (i. e., private and public resources); however, as already highlighted, without the contributions of companies, and counting with greater participation of the State. Over time, parties have become more dependent on the state (Krause et al., 2021; Krause, Rebello, y Silva, 2015) and the contribution of affiliates is insignificant for maintaining party survival.

Public resources are destined directly to the parties at the national level, and their leaders have the autonomy to distribute them to the candidates they want. It is fundamental to understand the model that enables a concentration of decision-making power in the distribution of public resources in the national leadership of the parties. The Constitution of the new Brazilian democracy (1988) granted full organizational autonomy to party organizations. They decide how to distribute their public resources, which are regulated in their statutes. In addition, party legislation (Law No. 9,096/1995) did not establish strict criteria for the use of these resources by parties.

In addition to the increase in public resources since 2015 with the Fundo Partidário and since 2017-18, with the creation of the fefc, another case of regulation of the supply of resources in Brazilian elections was the reduction in the volume of individual resources (self-financing) of candidates. As we mentioned earlier, in the context of scarce resources, with the ban on business donations in the 2016 municipal elections, there was a greater preponderance of own resources. Self-funded candidates were victorious in several major cities, which made this topic an agenda for legislators. At first, there was an attempt to reduce self-financing via Congress in 2017, but the initiative was vetoed by then-president Michel Temer that year. Therefore, in the 2018 general elections, this type of resource is still relevant. In 2019, already in the Bolsonaro government, the topic was discussed again. In this second moment, self-financing is limited to 10 % of the maximum expenditure for the position. That is, if a candidate was allowed by Law to raise up to 100,000 reais,2 only 10,000 could «come out of his own pocket». The measure already had effects in subsequent elections, in which candidates became less dependent on self-financing (Figure 2).

4. Brazilian legislation and demand regulation: unbalanced competition

Supply regulation did not impact to the same extent as the demand part. On this side of the relationship are candidates and parties. Campaigns are expensive around the world, but in Brazil, they can be even more expensive for a number of reasons, the electoral system and district size being some of them. A candidate for federal deputy, for example, disputes the election by running with candidates from other parties in addition to his own colleagues (open list) in an entire state (which is the electoral district), ranging from eight to 71 seats in dispute. The effect is fratricidal competition for resources between and within parties (Samuels, 2001a; 2001b; Cox y Thies, 2000).

The main measure to try to reduce the number of resources in recent years was the establishment of a spending ceiling for campaigns (still in 2015). This reduced the resources needed to be elected, but improvements are still needed (Avis et al., 2022; Calheiros et al., 2022).3 Between 2014 and 2018, the number of resources in electoral campaigns decreased but grew again in 2022, as the Special Campaign Financing Fund went from 1.7 billion reais4 to more than 4.9 billion reais5.6

The difference in revenue between elected and non-elected members of the Chamber of Deputies remained consistent throughout the analyzed period. On average, elected candidates raised six reais per voter,7 while non-elected candidates collected less than one real per voter in the district. InFigure 3, it is possible to observe these differences (the sum of resources undergoes a logarithmic transformation).

Undoubtedly, despite the recent changes that intended to reduce spending on political competition and the influence of economic power, it is possible to observe that the impact was not significant with regard to the conditions of competition between candidates. This is an element that directly affects the quality of political representation, as it makes it difficult for certain social and political segments to enter the political system and become competitive due to the lack of sufficient resources.

The effort from the legislative in the recent reforms carried out (2015, 2017, and 2019) did not specifically address the issue of competitive inequality. The Gini index for the distribution of resources among candidates running for federal deputy seats was 0.83 in 2010, rising to 0.84 in 2014, 0.81 in 2018, and falling to 0.73 in 2022. Despite the reduction, it is still possible to perceive a huge disparity. On this issue, the main «reformist» actors in recent years have been the Judiciary, especially the stf (Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Court) and tse.

5. Judicial Reform: The political minority issues

Significant changes were implemented in the relationship between money and politics in Brazil through the Judiciary. This is the case of the ban on corporate donations decided in 2015. The Federal Supreme Court (stf) concludes the judgment of adin (Ação Direta de Inconstitucionalidade, translated as Direct Action of Unconstitutionality) No. 4,650, complying with the claim by oab (Brazil’s Order of Attorneys), which decided to ban corporate donations to election campaigns and political parties (Rodrigues, 2019). Other changes were also made by the Judiciary, especially for the inclusion of minorities, particularly women and black candidates, firstly in 2018 and then in the 2020 elections.

The inclusion of women in political representation in Brazil is slow (Barbieri et al., 2019; Barnes y Holman, 2020; Driscoll et al., 2018; Sacchet, 2012; Sacchet y Speck, 2012) and still very limited. According to data from the Interparliamentary Union (uip), a global organization that brings together 193 countries, the country occupies only the 146th position in terms of female representation in its lower house. In institutional terms, there have been, since the 1990s, some mechanisms aimed at increasing the participation and representation of women, but still without substantive results.8 In institutional terms, since the 1990s, there have been some mechanisms aimed at increasing the participation and representation of women, but still without substantive results.

The first initiative was Law No. 9,100/1995. It regulated the 1996 municipal election that indicated the reservation of 20 % of vacancies in the party lists (in proportional elections) for women. Another initiative was the Election Law of 1997 (No. 9,097), which established the threshold of 30 % without the obligation to actually fill it in. Subsequently, only in 2009 did Law No. 12,034 establish the obligation to fill at least 30 % of vacancies on party lists for each sex. In order to encourage the participation and representation of women, the Federal Supreme Court (stf) decided in 2018 to ensure a minimum distribution of resources for female candidates. The court, when judging Direct Action of Unconstitutionality (adin) 5617, filed by the Attorney General’s Office (Procuradoria Geral da República, pgr), considered that Brazilian political parties would be obliged to distribute at least 30 % of the public resources received to female candidates. In this sense, the values coming from the Partisan Fund and the Special Campaign Financing Fund (fefc) should have a highlighted portion for women.

The resource incentive rule had a positive effect on political representation. As pointed out by Barbieri et al. (2019), changes in electoral financing rules in 2018 reduced the candidacy gap in terms of gender. The insertion of the fefc and the new distribution rules were positive so that, on average, female candidates were more electorally competitive. In 2014, for example, 51 federal deputies were elected, while in 2018 there were 78. In 2022, there is new growth, albeit timid: 91 women were elected.

As can be seen in Figure 4, there is an increase in the average amount of resources received by female candidates for federal deputy. In the case of female candidacies, the average party resources rise from 84 thousand reais (in 2014 and 2018) to more than 200 thousand in the following period. Thus decreasing the gap in relation to male candidates in the case of party resources.9 Not by chance, there is a growth in the number of elected federal deputies, but still far below the necessary. However, it is necessary to consider that the good intention of the rule also generated some unexpected perverse effects. The reaction was a significant existence of «orange» candidates (fake candidates), who nominally receive resources but, in practice, do not campaign (Wylie, Santos, y Marcelino, 2019). In these cases, money is diverted to male candidates.

Still concerned about expanding and diversifying representation, important decisions were made by the Judiciary and not by the Legislature to encourage black and brown candidacies. An old agenda of the Brazilian black movement is the inclusion of candidates and elected officials in institutional politics, given a series of historical inequalities and the legacy of slavery in the country (Campos y Machado, 2015; Firpo et al., 2022). The country has a mostly black population10 (54 %, according to ibge data11), but this group is underrepresented (23.9 % of federal deputies elected in 2018). After consulting the Federal Deputy Benedita da Silva (pt-rj) with the tse, the court determined that, from 2022, the value of public resources (fefc) would be distributed proportionally according to racial groups in the party lists. For example, if 30 % of candidates for a given party were black, at least this percentage should be passed on to these candidacies.12

The rule changes had some impact, but the gap remains between the analyzed periods (Figure 5). Between 2010 and 2018, on average, black candidates collected R$ 106,000; this figure increased to 260,000 in 2022. However, there is also growth for white candidates (from 258 to 395), which partly explains the only slight increase in black candidates in 2022 when compared to 2018, from 123 to 134 in the Chamber of Deputies. In addition, there were several complaints of erroneous racial classification between candidates. As the classification is done through self-declaration, several candidates declared themselves to be black and had previously classified themselves as white (Campos y Machado, 2015; Janusz, 2021; Janusz y Campos, 2021).13

The data on the representation of women and black candidates are important in themselves, as they are populations with a lot of representative weight in the composition of Brazilian society. These incentives, arising from the rule changes, demand a lot of attention. As noted earlier, the expected effects are not always achieved. Reactions to the norm are often instrumentalized and with perverse effects. Congress reacted and approved, in 2019, an amendment to the Constitution (amendment 111), which stipulates that the votes given to black and women candidates count twice for the distribution of public resources (fefc and Partisan Fund), starting in 2023. That is, if candidates fraud their declarations, this can «inflate» the resources destined for parties with bad practices. The creative and survival capacity of political actors in seeking alternatives to avoid losses in the face of inclusion policies is yet another example that good intentions in the rule do not by themselves guarantee expected effects.

It is still necessary to point out that «good intentions» in the rules can also bring difficulties in complying with them. Several parties, which have not met the quotas for women and black candidates, are mobilizing in the Legislature to extend the amnesty, including the last election of 2022. It is worth considering that this initiative has the support of leaders of parties from right to left.14

6. The Secret Budget and the 2022 Election Campaign

It has already been observed that the reforms and their effects do not always reach the expected results. There are intervening factors, such as the reactions of the actors directly involved with the rules of the game of electoral competition. One dimension is reactions that are not based on disobeying the rule but on creative alternatives for survival in the face of the new Law. Another dimension of reaction concerns the mobilization of pressure by actors who invest in changes to the new Law, with the aim of softening or rendering the new Law ineffective.

It is important, however, to consider that we have dealt so far with an analysis of the legal resources that circulate in electoral campaigns. That is, those that are declared with the tse and verified by the court later. With the risk that candidates with fraudulent declarations will be punished and may lose mandates. Although these values express a reality of Brazilian elections, they do reflect the whole picture (De Vries y Solaz, 2017; Evertsson, 2013; Samuels, 2001b). Other features need to be considered in the analysis.

In 2022, for example, the two presidential candidacies that went to the second round declared 130.5 million reais (Lula-pt, elected) and 105.5 million reais (Bolsonaro-pl, defeated). The amounts are close to the spending ceiling for the position (133 million) and show differences in relation to the sources. While for Lula, most of the donations came from public resources, for Bolsonaro, the resources came from private donors, especially big businessmen.15

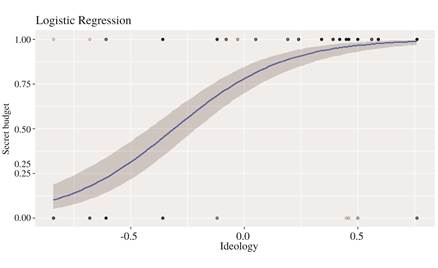

One instrument from the Executive branch that had an impact on electoral competition was the mobilization of Deputies in the instrumentalization of resources. In the case of the Chamber of Deputies, the secret budget, a form of pork barrel without transparency, available to deputies, represented 16 billion reais.16 The deputies with the highest amounts of this type of resource were, in the vast majority, re-elected in 2022. The Secret Budget was revealed through articles in the press,17 especially in Jornal Estado de São Paulo by journalist Breno Pires. The scheme operated from 2020 until the end of 2022 (when the stf declared it unconstitutional) and operated as follows: deputies requested resources from the Public Budget through the budget rapporteur in the Chamber, who then forwarded the requests to the corresponding ministries. When these were approved, the resources were destined to the places of the request without information about who was the deputy who requested and what the final destination (especially municipalities).18 For example, the mayor of a certain municipality requested funding for work in his city from a federal deputy. This, in turn, sent the request to the budget rapporteur in the Chamber. The rapporteur highlighted the value of the corresponding ministry executing the appeal. If approved, the resource was destined for the municipality. All procedures in this description, however, were hidden from the public.

In this «gray area», the control bodies, such as the Federal Court of Accounts (tcu), would not be able to act, which also facilitates corruption. Journalist Breno Pires himself provided information on the parliamentarians who most benefited from the Secret Budget. However, the information only accounts for those who were elected. This selection bias prevents more adequate inferences about the effect of this type of pork barrel, operated in the Bolsonaro government, and the 2022 election results.19 However, it allows us to observe that, for example, deputies from the government coalition were more benefited than opposition ones (the latter had a -97 % chance of receiving the resource). The data in Figure 6 demonstrate that the probability of receiving Secret Budget resources grows according to ideology. Bolsonaro, a far-right president with a support base in Congress of center and right-wing parties, benefited parliamentarians from these organizations. The test shown in Figure 6 indicates the probability of a deputy receiving some resource from the Secret Budget (according to data available in the press) and his ideology. The ideology variable is measured continuously, ranging from -1 (extreme left) to 1 (extreme right) (Power y Rodrigues-Silveira, 2019; Power y Zucco, 2009). The result indicates that the growth of a unit to the right of the party increased by more than 1,000 % the chance of a deputy receiving resources of this type.

7. Conclusion

The financing of politics, especially electoral, is a constant challenge to democracies and a central theme in political science. A key issue is ensuring balance in various dimensions of electoral competition. This applies both to the supply and demand of resources to achieve diversified and plural inclusion in political representation.

We selected the case of Brazil because it is a country that has recently undergone a series of changes in electoral financing legislation. These changes primarily result from a series of corruption allegations unveiled in the context of criminal investigations (Reis, 2020; Schaefer, 2022), and attack the supply of resources for parties and candidates. As pointed out by the literature, whether in the case of Latin America or other contexts, scandals can serve as catalysts for institutional change (Castañeda, 2018; Fuentes, 2018; Scarrow, 2004; Witko, 2007). A necessary but no sufficient condition for legislation changes.

The Brazilian case shows a tradition of some elements being maintained, despite repeated changes in the financing model. The Brazilian experience contributes to the argument that models of electoral financing must be evaluated in the context in which they are implemented.

We highlight four pressing elements. An element that remains throughout the trajectory of the new democracy is the persistence of imbalance in the source of electoral financing. First, with the experience of «slush funds» scandals in financing, the legalization of corporate financing was sought. Through this measure, the intention was to make the real funders of electoral campaigns transparent. This rule, by itself, did not avoid the scandal of specific economic groups dominating parties and governments. A country with high social inequality, little competitiveness, concentration, and cartelization of the economy demonstrated that another «recipe» was needed. The ban on business financing was reintroduced, but it was not observed that economic power could refrain from its impact in the electoral dispute with businessmen directly financing the election. The self-financing of candidacies also underscored the entry barrier for social segments in political representation. The reaction to compensate for the prohibition of business financing was the increase in public financing, which in turn did not bring a greater balance in the unequal and concentrating conditions in the financing of parties and candidates in electoral competition.

The second element that stands out in recent electoral experiences is the ability of actors, candidates and parties to react in order to remain in the electoral game, regardless of changes in the rules.

The third is the limits of initiatives for greater inclusion of women and black candidates in political representation with the increase in quotas and financial support for these groups. This demonstrates the need for inclusion policies that go beyond the electoral dispute.

Finally, especially in the 2022 election, the instrumentalization of the Executive power in the use of public resources in the electoral dispute was observed. The Bolsonaro government allocated a considerable sum of resources to his own re-election and the election of allies. Secret Budget data illustrates this dynamic. The further to the right the federal deputy on the political spectrum, the greater the chances of receiving pork barrel without the need for accountability to the Electoral control bodies (a focal point of discussion in Latin America).20 Despite the limitations of access to Secret Budget data, we think it is important to conjecture that this type of resource affected the balance in favor of a political group (the right and extreme right), which explains the election of the most significant right-wing group since the promulgation of the Federal Constitution of 1988.21 As for the variables that explain Bolsonaro’s non-re-election and the victory of Lula and the «Wide Front»,22 with a slight difference of 1.8 % in the second round, other structural and contextual factors need to be analyzed.23