Introduction

The demographic and epidemiological transition, made possible by the control of infectious diseases and reduction of maternal and child mortality, changed the clinical population profile, making chronic noncommunicable diseases prevalent in worldwide. With the natural evolution of the disease, at a certain moment, the modifying treatment is no longer effective, resulting in progression, loss of functionality and death. This period, from the moment the disease no longer responds to the treatment that intends to modify it until death, is defined by different terminologies: terminality, terminal illness, terminal care, end-of-life, actively dying, transition of care, and palliative care 1,2,3. The clinical terms have administrative, clinical and academic repercussions, as they imply the planning of care to be offered to the patient and family 4).

In the literature, especially in oncology and palliative care, there is no consensus on the definition of terminologies commonly used to refer to the final stage of illness and the end-of-life (1,3. Defining such terminologies can help in the qualification of communication between health professionals, researchers, and in the elaboration of public policies at the end-of-life. A review study identified a lack of consensus on the definition of "end-of-life," "terminal illness," "end-of-life care," actively dying," " transition of care" 1). The terms "end-of-life," "terminal illness," "end-of-life care" share a similar meaning: a progressive disease with a prognosis of months or days. This study did not evaluate, for example, publications and associations from countries in which the emergence and growth of palliative care, such as Latin American countries, is present.

Considering the lack of consensus on definitions of terminology used in the late stages of illness and life, as well as the increasing publication of end-of-life public policies and programs and palliative care in countries of the Asian and American continents, it is relevant to identify how such terminologies are used in scientific publications and knowledge societies in the area. In addition, recently the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC) proposed to the World Health Organization to update the definition of palliative care.

Thus, the objective of this study was to identify and map the definitions for palliative care, end of life, and terminally ill, used in oncology literature.

Materials and Method

We defined a scoping review based on the recommendations of the Joanna Brigs Institute (JBI) 6. A scoping review can be used to map key concepts that underlie a research area. For this study, we prepared a literature review protocol. It was evaluated by two external researchers, considering the population, context, and concepts (PCC) to be investigated. Thus, the research questions were: What concepts of palliative care, end-of-life, and terminal illness are, in adult oncology, adopted by leading palliative care societies in America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Oceania? What concepts of palliative care, end-of-life, and terminal illness, in the adult area, adopted in qualitative and quantitative approach research in the field of oncology?

Selection criteria

Regarding publications in journals, the inclusion criteria were: original articles and reflection articles published between January 2012 and December 2017, in English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish. For the selection of the original articles, we considered those in which the study population were people/patients aged 18 years old or older, suffering from cancer disease. We excluded editorials, theses, monographs, abstracts at scientific events, experience reports, review articles, and duplicate articles. Regarding Palliative Care Societies, we considered those from the five continents, from the adult area, with an updated web page, which countries presented the best position in The Economist's report on the quality of death 7.

Literature Search

We searched articles through double consultation and double collection in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. For this purpose, associated with the Boolean operator AND, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms "Terminally ill"; "Palliative Care"; "Oncology Service, Hospital." We selected articles after a consensus between the pairs of researchers, who identified the concepts. At first, we read of the "method" section. In the second stage, we read articles in full to determine the inclusion of studies for analysis. In order to ensure the quality of this step, we followed the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). In Figure 1, we summarize the PRISMA adapted to our study.

Organization Web site Search

Concerning palliative care societies, we consulted, between October and November 2018, the introductory pages of each website, and sought to identify glossaries that could indicate the meaning of the terminologies used by societies in their atlases, manuals or guides.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We organized the data in a spreadsheet program (LibreOffice Calc), which included: article title, authors, area, journal, journal impact factor, year of publication, objectives, method, number of study participants, the definition given for palliative care and/or terminally ill and/or end-of-life. We synthesized the definitions by simple frequency and percentage.

Results

Literature Search

Of the 51 articles analyzed, 46 were quantitative and five qualitative. Of these, seven presented fragmented results from the same study 8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Regarding the years of publication, 2014, 2016, and 2017 had more articles published, totaling, respectively, 14, 12, and 10 publications in the period. Of the areas to which the research was linked, 25 came from Medicine, 13 from multidisciplinary, six from Nursing, three from Psychology, two from Pharmacy, and one from Social Sciences.

Regarding countries, the following stands out Australia (10%), Canada (12%), South Korea (10%), United States (10%), Netherlands (8%), and Taiwan (12%). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (16%), Palliative Medicine (14%), American Journal Of Hospice & Palliative Medicine (6%), BMC Palliative Care (6%), and Palliative and Supportive Care (6%) were journals with most publications.

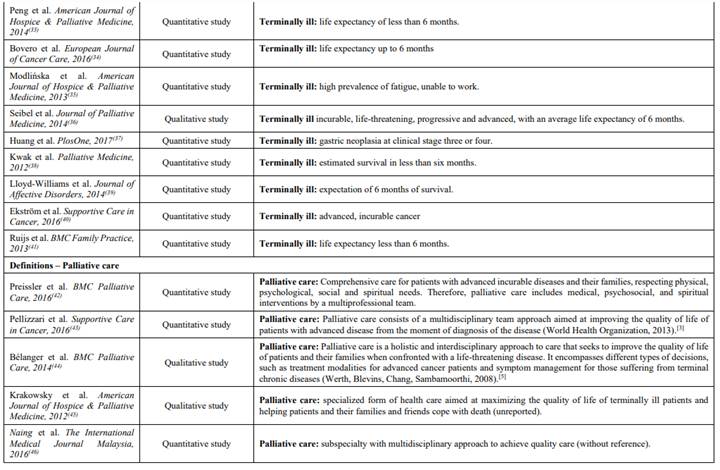

About the definitions: “end-of-life” was characterized in five studies, four quantitative and one qualitative; “palliative care” was defined in 15 studies, 11 quantitative and four qualitative and “terminally ill” appeared in 35 studies, 31 quantitative and five qualitative. (Appendix 1) 5,8,9,15,16,17,18,19,3,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,11,12,10,13,14,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,36,34,42,54,55,56. Among those, three articles presented two definitions. Two of them for “terminally ill” and “end-of-life” 5,9, another (36) presented for “palliative care and “terminally ill”. For this reason, in Appendix 1, we presented 55 definitions, although 51 articles have been analyzed.

Organization Web site Search

We consulted the websites of 25 Palliative Care Societies, of which 84% defined "palliative care," 24% defined "end-of-life," and 12% defined "terminally ill." Societies from countries with the lowest ranking in The Economist, located mainly on the American and African continents, presented fewer definitions for the three concepts. Three institutions featured one page on social network Facebook as an official website of the institution. Other societies had no website for a consultation. When defined "palliative care," in general, this makes reference to the definitions adopted by the World Health Organization or the Continental Society for the Area (Appendix 2).

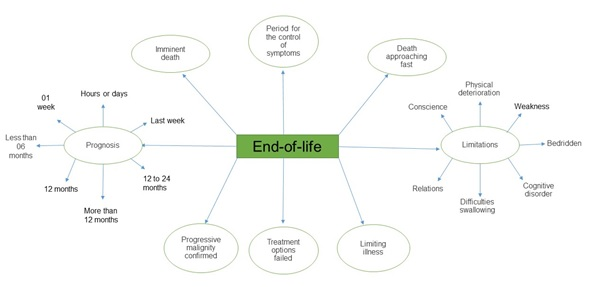

The concepts with the most definitions were "terminally ill" and "palliative care." "Terminally ill" is linked to a prognosis defined by a certain amount of months, days, or even hours of life. It is also associated with an incurable disease. Palliative care appears as specialized care provided by a multidisciplinary team, aimed at dignity and quality of life, through pain control and other symptoms. This care is also often related to diseases that no longer respond to modifying treatment and are life-threatening to the patient. Figures 2, 3 , and 4 presents a concept map with the standard definitions linked to the concepts.

In Table 1, we summarize and present a consensus of definitions for the concepts analyzed.

Discussion

In the international literature, quantitative approach studies are the ones that present the most definitions for situations involving palliative care and end-of-life. Especially when it comes to delimiting population and sample. This fact may indicate that the methodological designs linked to this approach tend to present more rigorous selection criteria for research participants. The need arises for qualitative studies to improve the inclusion criteria in the selection of study participants, based on definitions, terminologies, and concepts that can ensure greater validity and reliability to the results. Defining terms, establishing criteria, as well as adopting standardized language favors not only the methodological aspects of research but the transfer of knowledge to clinical practice, helping to consolidate knowledge areas (57).

Medicine stands out as the area of knowledge that has published most studies, demonstrating the growing appropriation of this knowledge about palliative care. Last years, palliative care has moved between a multidisciplinary domain and a new area of medical expertise (58.

Countries with the most publications presenting definitions of palliative and/or end-of-life care and/or terminal illness - Australia, Canada, South Korea, the United States, the Netherlands, and Taiwan - are also countries that rank well for refers to end-of-life quality in The Economist survey. In such countries, the quality of services provided by easy access to opioids, psychological support, and bereavement services, the appropriate number of specialists in the field, and community participation also help these countries to provide satisfactory Palliative Care 7. Countries with good access to this type of care have a high Human Development Index (HDI), i.e., have a high life expectancy, good access to education, and high gross national income 59).

The United States of America, for example, occupies the 13th position in the HDI world ranking, and the life expectancy of the population is 79.5 years old 60. An aspect that can contribute to the good development of palliative care in the USA is the presence of legislation on patients' rights at the end of life. As well as the presence of reference centers and associations on the subject, which is recognized worldwide. Nevertheless, limitations in symptom control (fatigue, ascites, dyspnea), lack of investment in research in the area, as well as the drop in the number of professionals, notably doctors and nurses, at different levels of care are barriers to integration and execution of palliative care in the UShealth care system 60.

Canada occupies the 12th position in the same ranking; the population has a life expectancy of 82.5 years old. The Canadian health care system provides for a structure based on access, quality, and long-term sustainability. In addition, this agreement is aimed at reforms in primary health care, information technology support, coverage for home care services, and facilitated access to medical and diagnostic equipment 61. In 2017, the Canadian Ministry of Health introduced a law providing for the development of palliative care structures 62.

Taiwan, a top-rated Asian country in The Economist ranking, since 2000, has patient rights legislation 63. From 2015, Taiwanese law provides that anyone with cognitive ability, over the age of 20, may draw up a document in the form of advance directives or advanced care plan, refusing to receive certain measures that have no clinical benefit, which may result in suffering 64).

When it comes to knowledge societies, Latin American and African countries still have weaknesses in structure, legislation, public policies, programs, and civil and health organizations in palliative care. A study 65 published in 2019 found that developing countries, i.e., those with medium to High Human Development Index (HDI), present more significant challenges in implementing palliative care practice. As well as countries with high infant and child mortality rates, infectious diseases, high rates of political corruption, and fragility in democracy. In such countries, the priority of health investments is for diseases that have not yet been controlled or eradicated and are the cause of high mortality rates. Countries with limited palliative care services also had difficulties in accessing other health services and challenges in promoting different forms of well-being 66).

Knowledge societies in the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, Switzerland, and Panama have definitions for Palliative Care and End of Life. Panamanian society is the only one among Latin American countries to present the definition for such concepts. The French Society for Palliative Care and Follow-up is the only one that provides definitions for the three concepts investigated in this study. France has a specific legislation for end-of-life behaviors, such as the elaboration of advance will directives, procedures for the implementation of continuous sedation until death, and for the limitation or withdrawal of treatments. In this country, palliative care is a recognized medical specialty. Furthermore, there are pedagogical training projects for doctors and nurses, oral opioids are available, and doctors of different specialties can prescribe them. These factors favor the development and consolidation of palliative care in France 67).

To define palliative care, the criteria used were advanced, terminal, incurable and severe diseases. In addition, quality of life was often related to this type of care, symptom management, specialized team care, family support, and coping with psychosocial and spiritual symptoms. The lack of consensus on the definition of palliative care is related to the conflicts that focus, especially when the specialized teams start the approach. Some professionals believe that a more advanced follow-up of the disease is necessary. Others think that the introduction of palliative care should occur when the disease is diagnosed, and others when it no longer responds to modifying treatment. In this regard, confusion is still evident between palliative care and supportive care. However, it is possible to observe that the authors agree with the objectives of such care. Lack of consensus hinders government funding and the opening of new programs in the area 68).

Regarding end-of-life, different criteria were defined to conceptualize it, which were associated with severe physical and cognitive deterioration, tumor progression, and malignancy. It was often associated with the last days or hours of life and in some prognostic literature less than six or twelve months of life 9,54,55,56. However, clinicians often stipulate prognoses intuitively, so they are inaccurate. Some scales aid this prognosis, but they depend on the patient, settings, and physicians. These uncertainties cause harm to both families and patients, given the expectations raised about this final period of life 69. The terminal illness was linked to different prognoses, ranging from days to less than one year of life. This term has also been associated with incurable, progressive diseases, and a period of intense deterioration in the quality of life. However, some authors consider that to classify a patient as a terminal; it is necessary to have knowledge about the estimated survival period for a given disease and to know the prognosis of most lethal chronic diseases. Other authors also state that the terminal condition is associated with the impossibility of restoring health and that in the absence of artificial procedures, death is achieved 13,14,18,20,21,40.

A limitation of this study is the language barrier. We consulted only articles and websites of societies with English, Spanish, Portuguese, and French. Moreover, we may have been misinterpreted some websites and even some articles. Due to possible translation problems, as the authors and proofreaders who selected the documents have Portuguese as their native language. Another limitation is the exclusion of review article. The studies with this methodological approach may have identified other terminologies and concepts that could endorse the definitions found. Finally, having restricted the area of oncology to search may also be a limiting factor of the conclusions presented.

Conclusions

In this article, we identified and mapped the definitions for palliative care, end-of-life, and terminally ill in oncology literature. The definitions were linked to the rapid progression of the disease, the decline in functionality, and the estimated lifetime ranging from to 12 months. There was a lack of consensus on definitions, even in the area of oncology, which has well-defined criteria and guidelines.

The implications of this study for research concern the possibility of standardizing terminologies, as well as helping to define inclusion and exclusion criteria of patients in other research, especially those with a qualitative approach. Likewise, it contributes to the consolidation of the area, favoring the adoption of common vocabulary in the academic and scientific circles when referring to patients with a terminally ill, at the end-of-life or in palliative care.

The implications for the practice are related to the fact that clarifying and defining terminologies can qualify palliative care. That way, it is possible to elaborate individualized care plans based on a common language adopted among all members of the interdisciplinary team.