Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados

versión impresa ISSN 1688-8375versión On-line ISSN 2393-6606

Enfermería (Montevideo) vol.13 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2024 Epub 01-Dic-2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/ech.v13i2.3929

Original Articles

Experiences of Anticipated Grief in Primary Informal Caregivers from the Metropolitan Region (Chile): Occupational Changes

1 Universidad de Chile, Chile, lrueda@uchile.cl

Introduction:

The loss of a loved one is constructed as an inevitable human experience, which generates an emotional experience that impacts both the individual experiencing the loss and his or her environment.

Objective:

To investigate the relationship between anticipated grief processes and alterations in the occupational participation of informal primary caregivers of terminally ill persons in the Metropolitan Region of Chile.

Method:

Qualitative approach with 7 individual semi-structured interviews with adult caregivers in the south and west of the region.

Results:

Experiences and subjectivities were categorized that express the importance that women attribute to the care of their relatives, with little emotional demonstration during this stage. In addition, categories such as routines and roles emerge, where many women prioritize caregiving; support networks, with frequent reports on the lack of help and tools beyond the economic; and areas of occupation affected, predominantly rest and sleep, although self-care and social participation are also mentioned.

Conclusion:

Although the process of anticipatory grief generates pain and self-exhaustion, it is informal caregiving that generates changes in the participation and quality of life of women caregivers.

Keywords: occupational therapy; grief; near-death experience; palliative care; end-of-life care

Introducción:

La pérdida de un ser querido se construye como una experiencia humana inevitable, que genera una vivencia emocional que impacta tanto al individuo que experimenta la pérdida como a su entorno.

Objetivo:

Investigar la relación entre los procesos de duelo anticipado y las alteraciones en la participación ocupacional de quienes fueron cuidadoras principales informales de personas con enfermedad terminal en la Región Metropolitana de Chile.

Método:

Enfoque cualitativo con 7 entrevistas semiestructuradas individuales a cuidadoras adultas en el sur y poniente de la región.

Resultados:

Fueron categorizadas experiencias y subjetividades que expresan la importancia que las mujeres atribuyen al cuidado de sus familiares, con una escasa demostración emocional durante esta etapa. Además, emergen categorías como rutinas y roles, donde muchas mujeres priorizan el cuidado; redes de apoyo, con relatos frecuentes sobre la falta de ayuda y herramientas más allá de lo económico; y áreas de ocupación afectadas, predominantemente el descanso y sueño, aunque también se menciona el autocuidado y la participación social.

Conclusión:

Si bien el proceso de duelo anticipado genera dolor y desgaste propio, es el cuidado informal lo que genera cambios en la participación y calidad de vida de las mujeres cuidadoras.

Palabras clave: terapia ocupacional; duelo; experiencia cercana a la muerte; cuidados paliativos; cuidados al final de la vida

Introdução:

A perda de um ente querido é construída como uma experiência humana inevitável, que gera uma vivência emocional que afeta tanto o indivíduo que experimenta a perda quanto seu entorno.

Objetivo:

investigar a relação entre os processos de luto antecipado e as alterações na participação ocupacional daquelas que foram cuidadoras primárias informais de pessoas com doença terminal na Região Metropolitana do Chile.

Método: abordagem qualitativa com 7 entrevistas individuais semiestruturadas com cuidadoras adultas no sul e oeste da região.

Resultados:

Foram categorizadas experiências e subjetividades que expressam a importância que as mulheres atribuem ao cuidado de seus familiares, com uma escassa demonstração emocional durante essa etapa. Além disso, surgem categorias como rotinas e papéis, em que muitas mulheres priorizam o cuidado; redes de apoio, com relatos frequentes sobre a falta de ajuda e ferramentas além das econômicas; e áreas de ocupação afetadas, predominantemente o descanso e o sono, embora o autocuidado e a participação social também sejam mencionados.

Conclusão:

Embora o processo de luto antecipado gere dor e desgaste próprio, é o cuidado informal que gera mudanças na participação e na qualidade de vida das mulheres cuidadoras.

Palavras-chave: terapia ocupacional; luto; experiência de quase morte; cuidados paliativos; cuidados no final da vida

Introduction

Through emotional bonds, individuals construct and nourish their relationships with others, simultaneously shaping their individual and collective identities. Consequently, the loss of a loved one, an unwanted yet inevitable aspect of human experience, creates a dramatic emotional experience for the person and their surroundings, altering customs, routines, life expectations, and the meanings attributed to daily activities. 1

Grief, therefore, becomes a common experience in everyday life and can manifest itself before, during, or after the death of a loved one. This process evolves over time, and those who experience it undergo various stages and a learning phase, resulting in changes in daily life and the individual’s identity. 2

In this way, considering that personal, family, and community aspects are involved, there is no singular way to approach grief. Some authors suggest that it is not a linear process; rather, it involves various emotional and behavioral reactions that lead to the reconstruction of the bond. 3

Grief can even occur before the death of a loved one; this process is known as anticipatory grief. According to Calabuig et al., anticipatory grief is a phenomenon that allows individuals to interpret loss as a natural process and, in turn, develop strategies to face the farewell and adjust to the new reality. 4

Knowing in advance about the arrival of this event within a predicted time frame can transform this instance into one of planning and socializing the experience, where there is support and preparation for the person and their environment, defining the types of help and attention needed, out of respect for a good death. Ideally, this should promote that individuals have the necessary tools to face death and the grieving processes in a healthy and conscious manner. 4

This anticipatory grief process begins from the moment of diagnosis of the patient, who suffers from progressive physical and mental deterioration, and it is the family caregiver who experiences these losses in the patient. 5 These diagnoses are known as terminal illnesses, where the person has a pathology that, in the eyes of specialists, has no cure and is in the final stages of their illness, or is in the process of dying.6) Due to the physical wear that some of these diagnoses entail, the assistance of another person to maintain care is necessary. Thus, end-of-life care demands particular attention, whose requirements increase as the terminal illness that anticipates grief progresses.(6)

The new role of caring for a person with a terminal illness is defined as a significant family process that can be a source of stress and emotional overload.7 This challenge is linked to the responsibilities this new role entails, as well as the attempt to fulfill previously held roles, striving for a balance between them. (8) From an occupational perspective, the demands associated with the role of the primary caregiver lead to an occupational imbalance that must be addressed by developing skills, restructuring routines, and other measures. 8

End-of-life care, predominantly the responsibility of women, requires a high level of specialization and extension, and thus, incurs significant economic costs. 9 This situation is contradictory given the unpaid nature of the informal care provided by women, most of whom are family members, who bear these costs not covered by the State, thereby contributing to a state of impoverishment and precariousness. This confines care strictly to the domestic-private sphere and ultimately leads to the postponement or abandonment of the vital projects of female caregivers. 9)

Given this background, caregiving can be seen as a demanding task, where the quality of life of the caregivers is adversely affected. 10 Adding to the complexity of experiencing anticipatory grief, informal caregivers often lack the training for the various types of care they provide. Thus, caregiving can become a challenging task, causing fatigue, emotional and physical wear, and stress, leading to a state of overload that compromises their well-being. 10

In Chile, it is estimated that 85 % of caregiving is performed by female family members, who mostly identify as informal caregivers, meaning they do not receive payment for their work. (11) Furthermore, a high percentage dedicate more than 8 hours daily to this role, and more than half also engage in domestic chores. 11

Given the aforementioned, being an informal caregiver in Chile involves facing a complex scenario. For this reason, over recent years, various initiatives have been launched to recognize and provide support to this sector of the population. In 2021, Law 21,380 was enacted, recognizing caregivers’ right to preferential health care. 12 In November 2022, the creation of a national registry of caregivers was announced, who will receive a credential for this purpose, as a form of state recognition for their caregiving efforts. 13

Despite these advances, informal caregivers continue to face daily challenges such as the increasing demand for care, considering the demographic changes, particularly the increase in life expectancy. 14 This necessitates that Occupational Therapy projects interventions to adapt the caregivers, which is why this project focuses on gathering experiences from individuals who have already undergone these processes, constituting a remembrance of the person’s occupational history. In this sense, the project aims to explore the life histories of caregivers from their memories, recognizing that the experience of grief is not a state but a process, and there is no single way to respond to loss; it depends on the caregiver’s culture, their multiple contexts, and the bond they had with the deceased. (15

Therefore, this research aims to describe the relationship between the processes of anticipated grief and the occupational participation and quality of life of those who were informal caregivers for five years or more to people with terminal illnesses in municipalities in the southern and western sectors of the Metropolitan Region. It also seeks to recognize the influence of cultural aspects on the conceptualizations of death in the context of people who have experienced anticipated grief; to identify the occupational areas affected by informal caregivers through their narratives; and finally, to explore the routines and roles those informal caregivers adopted during the grieving process.

Method

The focus of this study is qualitative research, based on individual interviews-a method for collecting and evaluating non-standardized data. This approach emphasizes understanding phenomena from the perspective of people in their natural contexts and their relationships with these environments, stressing their viewpoints, understandings, and meanings.16 The method is justified as it aims to illuminate the experiences of caregivers, leading to an understanding, from their narratives, of how informally caring for a family member affects various occupational aspects of their life.

Furthermore, the research operates within an interpretive paradigm, focusing on subjective phenomena to describe them in depth and interpret their meanings.17 This aligns with the proposed approach and the theme of the research, asserting that anticipated grief is a normative process. Both the individual characteristics of the person, the bond with the deceased, and the context determine the complete grief experience, thus configuring it as a subjective process. 4

The participant pool for this study includes women over 18 years of age who have provided informal (unpaid) care to relatives diagnosed with a terminal illness. The care must have been provided five years ago or more, as of 2023. The participants reside in the western (5) or southern (2) sectors of the Metropolitan Region, including urban, rural, and mixed municipalities with a higher female population and significant socioeconomic and educational disparities compared to other municipalities in the region. 18

The sample selection criteria for this research were devised in line with the study’s objectives, ensuring sample coherence.

Inclusion Criteria

- Women aged 18 to 65.

- Reside in the western sector of the RM.

- Have been a caregiver for at least six months to a person with a terminal illness to whom they are emotionally close.

- Have been an informal caregiver.

- Have experienced the death of the care recipient at least five years ago but no more than ten years ago.

Exclusion Criteria

- Having an emotional bond between the caregiver and the care recipient as a mother.

- A history of psychiatric pathologies.

- Educational level lower than complete secondary education.

- Any form of disability or dependency.

- Experiencing complicated grief.

The sample of volunteer participants consisted of seven female caregivers, recruited through an open call on Instagram, the Consejo de Estudiantes de la Salud and the Universidad de Chile communities on the U-Cursos platform, constituting a convenience sample. The research’s objectives, along with the potential social and occupational therapy benefits of participation, were explained. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without prejudice. After being informed about the general aspects of the project, they were presented with an informed consent form and asked about their willingness to be audio-recorded during the interview.

The caregivers participated in a semi-structured interview developed by the students of the research project and supervised by the occupational therapist tutor in charge, conducted during October and November 2023. The interview was designed based on the literature concerning anticipated grief and divided into parts focusing on sociodemographic and personal characterization (age, gender, main occupation, relationship with the care recipient, among others), and the caregivers’ experiences, including questions about family restructuring and personal routine changes.

These procedures adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, primarily aimed at promoting and safeguarding the well-being, dignity, and respect of the individuals involved. The information will be used anonymously and solely for academic purposes, disclosing only the necessary data for the research context. The research project received approval from the Ethics Committee for Research in Human Subjects (CEISH) of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Chile.

The participants’ narratives are analyzed according to axes related to occupational areas, understood as "daily activities that people perform as individuals, in families, and within communities to occupy time and give meaning and purpose to life", 19p. 6) which are crucial as they provide identity and a sense of competence to individuals. The occupational changes of the caregivers are thus analyzed from these perspectives.

Results

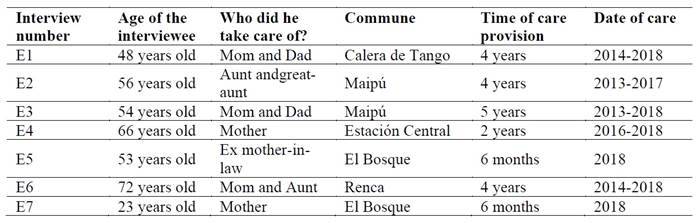

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the seven participants interviewed for the study.

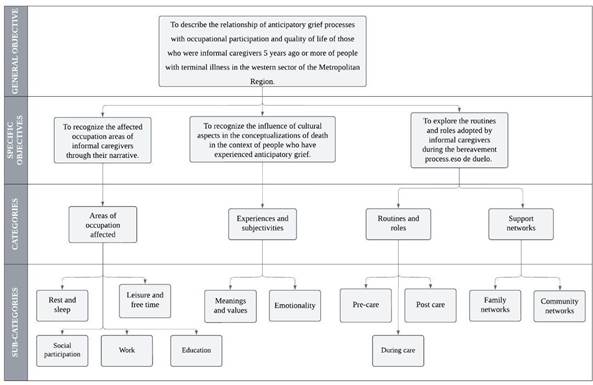

Based on the responses collected, four major analytical categories were identified, each with corresponding subcategories. These categories were designed to meet the objectives of this research and are depicted in the flowchart of objectives, categories, and subcategories (Figure 1).

Areas of occupation affected

Six areas were analyzed: rest and sleep, leisure and free time, work, education, and social participation.

Rest and sleep

Regarding rest and sleep, the vast majority of the interviewees reported significant changes. As primary caregivers, their role often involved staying up at night to accompany and assist the person being cared for.

I couldn’t sleep at night because I was worried about her getting up. Of course, she didn’t want to get up during the day-she had spent the whole night awake (E4).

Some interviewees stated that despite their exhaustion, they could not sleep:

I could be dead tired, but I just couldn’t sleep (E3).

Additionally, in this category, two of the interviewees had to resort to pharmacological aids to manage sleep while providing care. One interviewee reflected on the aftermath of the caregiving period:

We never realized how tired we were until after she passed away (E2).

Leisure and free time

Leisure and free time refer to activities that a person voluntarily engages in based on personal interests and motivations. These activities occur outside the framework of essential occupations such as work, education, basic activities of daily living, and rest/sleep.

In this context, two interviewees (E4 and E5) reported having small intervals within their caregiving routines where they could engage in activities unrelated to caregiving. Conversely, three participants (E2, E3, and E6) admitted that they have not dedicated time to leisure and free time activities to date and have experienced difficulties in doing so.

Work/Education

Work and education activities relate to social or economic productivity. These areas were significantly impacted among the caregivers interviewed.

Three of the seven interviewees (E4, E5, and E6) were forced to leave their jobs. Additionally, three others had to adapt to their circumstances: for instance, the third interviewee managed to merge her role as a caregiver with her profession as a teacher by starting to teach online classes, a change also influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Other adaptations included reducing work hours (E6) and family planning to continue working (E2). The youngest participant in the study (E7) mentioned that she was not employed before or after her caregiving period, but she did discontinue her studies to provide full-time care for her family member.

Social participation

Social participation is one of the occupational areas most impacted according to the caregivers’ accounts. The lack of involvement in social activities can largely be attributed to two main factors. Firstly, the inability to leave the person being cared for with someone else due to a lack of support networks significantly affected social participation.

Yes, it changed a lot. I stopped doing many things. I have very few friends, maybe three or four, who used to visit each other’s homes with our spouses and children. We even went on vacations together. I stopped inviting them over. Then, gradually, I also stopped visiting their homes; I would only go for their birthdays and would return early. I sometimes asked my siblings if they could stay with them, but they would say, “but it’s your responsibility”, or “sure, but make sure you’re back by 6” (E3).

Another significant factor is the desire to spend as much time as possible with the loved one due to the imminent sense of loss from the terminal diagnosis.

When you feel like you’re about to lose someone so important, you don’t want to spend your time with anyone else. You want to make the most of every moment. So, I stopped seeing my friends. I wasn’t interested in socializing with others. I just wanted to be with her as much as possible (E6).

In this category, another interviewee recognizes and underscores the importance of maintaining social interactions during the caregiving period:

I hardly saw anyone. And that was really tough because sociability, being able to talk to people, is crucial. It helps tremendously when you’re in such a situation (E4).

Experiences/subjectivities

Meanings and values

Values are intrinsically linked to human existence as they determine and guide behavior. They shape people’s ideas, thoughts, and feelings, influencing their way of relating to others and serving as guides that direct everyday actions and decisions.

In most interviews, a strong expression of values related to the family is evident in the context of caregiving.

Many caregivers felt particularly motivated to care for their family member due to the meaning and emotional bond previously established with the person (E2, E5, E7). Furthermore, many interviewees expressed a sense of duty or obligation, feeling indebted to their loved ones for past actions, and viewed their care as a way of “giving back” (E4, E6, E7). Solidarity emerged as a universal value of significant importance among the interviewees (E1, E6, E7). They reported that they provided care “from the heart” and out of “basic humanity”, guided by a sense of solidarity that motivated them to help selflessly.

Regarding their outlook on life and work, interviewees E4, E5, and E6 noted that these experiences had a positive impact, as they learned to “make the most of the present” and “enjoy life more”. Interviewees E1, E6, and E7 expressed satisfaction and tranquility in retrospect about the care they provided, affirming that they gave their best and have no regrets. However, interviewee E3, while stating that she also “gave her all”, admits she feels she “could have done more”, making her the only caregiver to express dissatisfaction, which could be attributed to specific characteristics of the interviewee.

Additionally, values attributed to Christianity were noted, specifically relating to the figure of God as a way of understanding the value of life and the concept of earthly death as a transition to eternal life, providing hope and consolation for some interviewees (E3, E5, E7). Ultimately, these values and meanings hold significant importance and prioritize caring for a family member, often over the caregivers’ own needs (E1, E6, E7).

Emotionality

Emotionality is an essential aspect of the human experience. It is important to note that emotions and actions interact with each other and cannot be understood separately, as they involve cultural, social, religious, and moral factors.

Based on this understanding, the narratives reveal an emotional journey marked by feelings of sadness, anger, frustration, and abandonment when recalling their experiences of anticipated grief. All interviewees, without exception, described how painful it was to witness their relative’s deterioration due to illness, labeling the caregiving period as one of the most challenging and intense experiences of their lives. After the caregiving ended, some interviewees (E1, E3, E4, and E6) reported feelings of sadness due to the loss of their relative and the emptiness left by the cessation of their caregiving roles. Specifically, interviewees E1 and E3 stated that after this event, “their lives no longer had meaning”.

During the caregiving period, several interviewees reported feelings of suffocation and confinement due to the relentless demands of caregiving tasks, which forced them to repress their emotions during this time (E3, E4, and E6). Additionally, two interviewees expressed disappointment with other family members, as they had expected more support (E3 and E4).

The concept of emotional anesthesia was mentioned by interviewees E1, E4, E6, and E7, describing moments of apparent insensitivity that serve as a protective response to the overwhelming emotions associated with caregiving. This disconnection or repression of emotions acts as a form of self-preservation, allowing caregivers to manage their responsibilities more practically and rationally. This mechanism is underscored by reports of significant mental exhaustion and stress, which were somewhat alleviated by feelings of affection and positive relationships with the person being cared for (E2, E5, and E7).

Particularly noteworthy is the account from interviewee 4, who experienced intense anger, frustration, and rejection of her situation, struggling to accept the progression of her loved one’s illness. This led to a phase of depersonalization where she felt she had “dehumanized” herself for a time, treating the person she cared for akin to a doll. A similar sentiment was expressed in interview 2, where the caregiver described treating the person being cared for “like a baby”, revealing a common theme in both accounts.

Routines and roles

Pre-care

For most participants, the role of caregiver was already a part of their daily lives before they began caring for their ill family members. Several had previously cared for their children or others, dedicating a significant portion of their day to these responsibilities, in addition to performing domestic chores. Three of the interviewees were also employed. However, once their family members were diagnosed, all gave up their professional roles and/or prioritized their family members’ care over other responsibilities.

During care

The roles of caregivers in performing their duties are categorized into five major areas.

1. Assisting the person being cared for with tasks such as feeding, bathing, dressing, bathroom and toilet hygiene, personal hygiene, toileting, and functional mobility.

Changing her, bathing her because I was the only one who dared to bathe her (E1).

It was very difficult to change her, bathe her, because they were only self-sufficient in some things; yes, they could go to the bathroom, but you had to help them bathe (E3).

I gave her breakfast, I took care of her so she could eat, because everything had to be given to her slowly and well blended because she no longer had the strength to swallow food (E5).

2. Assisting the person being cared for in instrumental daily living activities, mainly financial management, household management, religious expression, meal preparation, and cleaning.

If she had to be taken to the farm, she wanted me to take her (E1).

And I dedicated myself only to her, to maintaining her house, the place where she lived (...) She was a very Catholic person, very Catholic, and she asked me to pray the rosary every day (E5).

I prepared their food accordingly, because my mother was diabetic and, well, all her food was special (E6).

3. Assisting the person being cared for in leisure and free time activities.

She needed us all the time, from company because people forget, to you doing what you do when people are sick, they also need care, to talk, to stimulate their imagination (E2).

Well, and as I told you, she wanted me to be here with her. So I was already knitting, I was talking to her, suddenly we were drawing, we were painting like mandalas (E4).

4. Assisting the person being cared for in health management, that is, symptom and condition management, medication management, personal care device management, and communication with the health system.

If she had to be taken to the doctor, she wanted me to take her (E1).

I had each of their own boxes of medicines, their things, with their name, with their time, with everything, so in case I forgot something, everything was there (E3).

I gave her her medications at the corresponding time (E5).

And I took her to the doctor (E6).

I was the one who was with her all day, all night, I took care of her medicines, accompanied her to the doctor, everything, everything, the exams, I did all of that (E7).

5. Assisting with tasks and roles associated with their own home, such as cooking or cleaning, as well as caring for other people in their family unit, children, for example, which often had to be delegated to husbands or other relatives.

So when I arrived (at her house), eh, I cooked, right? I did the laundry, eh, I cleaned on the weekend, my children were thankfully already grown up so I didn’t do chores with them (E3).

Post care

After their caregiving duties ended, all the interviewees reported that they resumed the activities and roles they had before becoming caregivers. They returned to their previous occupations related to work, education, rest and sleep, and social participation.

I resumed my friendships and the outings we usually had, which I don’t know about the outings we did at the end of the month, we got together, sometimes at my house, at my friends’ houses or we went somewhere (E5).

Three interviewees (E1, E2, E3) described a sense of disorientation after the death of the person they cared for.

We never realized how tired we were until she left, and then it was like, now what are we going to do? We had free time (E2). After feeling like I didn’t have anyone else to care for, I was like, “Ohh, okay”. The first thing I did was take more hours at school (E3).

However, interviewee 1 mentions how complex this new reality was for her, showing how different the adaptation processes are for each caregiver.

I did all the paperwork and then reality hit. I didn’t know what to do anymore. My life no longer had meaning. Then grief came to me, and I was really bad (E1).

Most interviewees reported having more time for themselves and showed a renewed focus on caring for their children, valuing their role as caregivers and seeking new activities aligned with their personal interests.

I started doing things for myself; that’s when I started to give myself time. I finished studying, I took a manicurist course that I was working on too (E1). Now that I’m here, I dedicated more time to myself. I gave myself my time. I tried to see if I could find a boyfriend, but it’s hard, it’s hard to get back to normal life again (E5). The truth is that I feel calmer and I promised myself to take care of myself now because I put myself aside a lot. I left many things undone for myself while I was taking care of them (E6).

Additionally, four of the interviewees continued in their role as caregivers, two of them informally, caring for a family member again, and two decided to return to caregiving as their profession.

Last year I finished, I graduated from high school, I took the PAES, and today I am studying to be a nursing technician because I feel that this is my vocation, to help (E1).

Support networks

For this research, support networks were subdivided into two categories: family and community. Family support refers to assistance from people with a blood or legal connection to the person being cared for. Community support includes assistance from institutions such as healthcare, educational, religious entities, or other non-profit organizations.

Family

Most interviewees reported receiving some form of financial aid or help with basic instrumental life activities from family members (E1, E2, E3, E4, E5, and E7).

Most of the family members were adults; they helped us in other ways, such as bringing us lunch or vegetables and things to make baby food (E2).

However, those interviewed who assumed the care of elderly women and men (E3, E4, E5, E6), mostly mothers and fathers, constituted themselves as the main caregivers over the other children of the sick person, assuming the role completely and only receiving economic support and/or care benefits sporadically from the rest of the family.

It was like Halley’s Comet (referring to her brother). He would show up, say “Hi, Mommy, how are you?” and “How are you?” Then he’d go, “I’m going to use the bathroom”, and comment, “I see that my mommy is really fine”. Of course she’s fine! Because I take care of washing her, cleaning her, feeding her. Everyone who comes sees her clean, pretty, sitting there, calm, but I need someone to take care of her for a whole day so I can go out, do my things, maybe visit my grandson at my son’s house. But no, he always says, “It’s not that I can’t, it’s that I don’t have time because...” and then leaves after 5-10 minutes with a thousand excuses (E4).

On the other hand, only one interviewee reported receiving no help at all, highlighting the significant personal sacrifice.

It was quite a sacrifice, because I didn’t get any help from my aunt. I had to take care of her alone and take her wherever she wanted to go (E6).

Community

Regarding community support from public health services such as the Home Care Program for People with Severe Dependency, care at CESFAM, COSAM, public hospitals, and more, more than half of the interviewees (E1, E2, E3, E4, E6, and E7) mentioned having been beneficiaries. Nevertheless, they felt that the support was insufficient:

The bedridden team once invited me to a talk where they told us wonderful things about the support they offered, but we never received any actual support. No psychologist, no counselor, nothing. They just came to see my mother, sent a kinesiologist, a doctor, a podiatrist, a nutritionist, but as far as helping the caregiver? Nothing, nothing at all (E4).

Discussion

The research provided an answer to the stated objective of describing the relationship between anticipated grief processes, occupational participation and quality of life of those who were informal caregivers for five or more years. It’s clear that anticipated grief induces pain, emotional, social, and physical exhaustion in caregivers. These outcomes are attributed to the demands of informal caregiving, which ultimately lead to changes in occupational participation and the quality of life for women

The involvement in caregiving activities often results in what can be described as emotional anesthesia, where caregivers find themselves unable to express their emotions or thoughts, exacerbated by the absence of adequate support networks and emotional containment during the caregiving period. This often leads to a sense of “post-care emptiness”, which, although typically temporary, allows caregivers to either resume their previous occupations or embark on new ones.

Regarding their emotional state, informal caregivers frequently feel a loss of control over their lives from the moment their family member falls ill. While the effectiveness of their roles and social relationships can sometimes be maintained, interpersonal relationships often suffer due to the lack of time.

The role of caring for a dependent person at the end of life is recognized as a process that can be a source of stress and emotional overload, as supported by the cited works. This aligns with the results of this study, which highlight a narrative marked by feelings of sadness, anger, frustration, and pain.7 For example, Fernández and Herrera note that caregiving can become an arduous task that leads to fatigue, emotional and physical exhaustion, and ultimately, an overload that compromises the well-being of the caregiver and adversely affects their quality of life, 10 as detailed in the results presented. Similarly, Fonseca 8 states that the demands associated with the role of primary caregiver lead to occupational imbalance, which aligns with the findings of this research. Significant changes in the performance patterns of the interviewees were observed, particularly in the areas of rest and sleep and social participation. This is attributed to a restructuring of routines to prioritize the needs of the person being cared for, resulting in the caregivers putting their own needs on hold. 8

E The literature frequently mentions that providing care necessitates a complete family restructuring.3,7 The findings of this research suggest that this restructuring primarily and uniquely affects the lives of informal primary caregivers, even in the presence of other direct relatives. This often stems from these relatives’ lack of interest in caregiving or their neglect of the situation, knowing that someone else is providing the necessary care.

This situation aligns with the historical trend of feminization of care, characterized by a narrative that positions caregiving as a woman’s duty, resulting in the burden of care and all its associated responsibilities falling almost exclusively on women. (8, 9, 10, 14) In Chile, this pattern holds true, as the role of caregiver is predominantly undertaken by female family members, 11 who identify themselves as informal caregivers. The interviewees describe their empathetic feminine nature, their nurturing instincts, and an inherent desire to protect the family.

According to Aponte et al., the empathy that caregivers develop due to witnessing the suffering and deterioration-both physical and cognitive-of the person they care for, and spending a significant portion or all of their day with them, might lessen the emotional pain following the death of the loved one, framing death as a necessary release. (5

The above situation may be related to the concentration of responsibilities centered around the care of the sick person. The feeling of guilt that caregivers often experience when they cease caregiving activities-due to their deep empathy with the suffering of their loved ones-might lead them to persist in their caregiving roles. (5) This dynamic, akin to the feminization of care, often results in other family members assuming more passive roles, a scenario reported by more than half of the interviewees.

This is reflected in the everyday lives of these women, who feel the weight of a lack of appreciation from their social circles and limited opportunities for leisure and relaxation. This aligns with what has been discussed previously regarding the feminization of care, where the routines of female caregivers blur the lines between unpaid work and leisure. In many cases, leisure is not only seen as unnecessary but also as a hindrance to fulfilling traditional female roles.

Conclusion

It is crucial that healthcare not only focus on individuals suffering from an illness but also on their caregivers. Caregivers often face complex and demanding situations at both physical and emotional levels, which can deteriorate their quality of life. They experience what is known as anticipated grief, during which they may suppress their emotions to fully dedicate themselves to caring for the ill person.

The experiences of these informal caregivers highlight that their satisfactory participation in various occupational areas is compromised. Occupational Therapy can play a crucial role in preventing or compensating for these imbalances, thereby enhancing the well-being of both caregivers and those they care for.

Further research on the impact of the role of informal caregivers is essential, particularly focusing on areas such as daily living activities. It is important to develop and implement intervention programs within the profession and contribute to the creation of public policies that effectively address the needs of caregivers. This underscores the necessity for financial support from health teams specialized in comprehensive end-of-life care for both patients and their caregivers. Additionally, highlighting the burden of care, understanding its effects, and recognizing the historical role of women in caregiving are vital steps toward acknowledging and addressing these challenges.

As a limitation of the study, it should be noted that the interviews with participants were not conducted systematically but rather through several meetings. This approach meant that contributions had to be reconstructed and, ultimately, the analysis categories were agreed upon and completed through the compilation of the researchers’ observations.

REFERENCES

1. Briceño Ribot C. Necesidades de cuidados al final de la vida en personas mayores con dependencia por condiciones crónicas desde la perspectiva de los cuidadores informales y profesionales de la salud: un reto a nuestro actual sistema sanitario (Tesis de Maestría). Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile;2017. Disponible en: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/175461 [ Links ]

2. Alonso L, Ramos M, Barreto P, Pérez M. Modelos Psicológicos del Duelo: Una Revisión Teórica. Calidad DE Vida y Salud. 2019;12(1):65-75. http://revistacdvs.uflo.edu.ar/index.php/CdVUFLO/article/view/176 [ Links ]

3. García Hernández AM, Rodríguez Álvaro M, Brito Brito PR, Fernández Gutiérrez DA, Martínez Alberto CE, Marrero González CM. Duelo adaptativo, no adaptativo y continuidad de vínculos. Rev Ene Enferm. 2021;15(1):1242. Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1988-348X2021000100001 [ Links ]

4. Calabuig K, Lacomba-Trejo L, Pérez-Marín M. Duelo anticipado en familiares de personas con enfermedad de Alzheimer: análisis del discurso. Av Psicol Latinoam. 2021;39(2):1-17. doi: 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.8436 [ Links ]

5. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional. Ley fácil: Reconocimiento y protección de los derechos de las personas con enfermedades terminales y el buen morir (Internet). Santiago, Chile: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile; 2023. Disponible en: https://www.bcn.cl/portal/leyfacil/recurso/reconocimiento-y-proteccion-de-los-derechos-de-las-personas-con-enfermedades-terminales-y-el-buen-morir [ Links ]

6. Aponte V, Valdivia F, Ponce F, García F. Duelo anticipado y afrontamiento al estrés en cuidadores informales de personas de la tercera edad. Liberabit. 2022;28(2):e621. doi: 10.24265/liberabit.2022.v28n2.621 [ Links ]

7. Hernández E, Llibre JD, Bosch R, Zayas T. Demencia y factores de riesgo en cuidadores informales. Rev Cub Med Gen Integr. 2019;34(4):53-63. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S0864-21252018000400007&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt [ Links ]

8. Fonseca I. Influencia del género en la salud de las mujeres cuidadoras familiares. Rev Chil Ter Ocup. 2020;20(2):211-219. doi: 10.5354/0719-5346.2020.51517 [ Links ]

9. Grandón D. Lo personal es político: experiencias de mujeres cuidadoras informales de personas adultas en situación de dependencia, en Santiago de Chile (Tesis de Maestría). Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile; 2019. Disponible en: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/175934 [ Links ]

10. Fernández M, Herrera M. El efecto del cuidado informal en la salud de los cuidadores familiares de personas mayores dependientes en Chile. Rev Méd Chile. 2020;148(1):30-36. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872020000100030 [ Links ]

11. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia. Encuesta de Bienestar Social (Internet). Santiago, Chile: Gobierno de Chile; 2021. Disponible en: https://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/encuesta-bienestar-social-2021 [ Links ]

12. Chile. Ley 21.380 de 12 de octubre de 2021. Reconoce a los cuidadores o cuidadoras el derecho a la atención preferente en el ámbito de la salud. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1166847 [ Links ]

13. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia. Presidente Boric entrega las primeras Credenciales de Personas Cuidadoras: Desde hoy podrán identificarse a través del Registro Social de Hogares (Internet). Santiago, Chile: Gobierno de Chile; 2022. Disponible en: https://www.desarrollosocialyfamilia.gob.cl/noticias/presidente-boric-entrega-las-primeras-credenciales-de-personas-cuidadoras-desde-hoy-podran-identific [ Links ]

14. Vaquiro S, Stiepovich J. Cuidado informal, un reto asumido por la mujer. Cienc Enferm. 2010;16(2):9-16. Disponible en: https://www.scielo.cl/pdf/cienf/v16n2/art_02.pdf [ Links ]

15. Parro-Jiménez E, Morán N, Gesteira C, Sanz J, García-Vera M. Duelo complicado: una revisión sistemática de la prevalencia, diagnóstico, factores de riesgo y de protección en población adulta de España. An Psicol. 2021;37(2):189-201. doi: 10.6018/analesps.443271 [ Links ]

16. Hernández R, Fernández C, Baptista P. Metodología de la investigación. 6ª ed. México D.F.: McGraw Hill Education; 2014. [ Links ]

17. Santos Y. ¿Cómo se pueden aplicar los distintos paradigmas de la investigación científica a la cultura física y el deporte? Rev Electrón Cienc Innov Tecnol Deport. 2010;(11):1-10. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6174061.pdf [ Links ]

18. Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias. Región Metropolitana de Santiago (Internet). Santiago, Chile: Gobierno de Chile . Disponible en: https://www.odepa.gob.cl/estadisticas-del-sector/ficha-nacional-y-regionales [ Links ]

19. American Occupational Therapy Association. Marco de Trabajo para la Práctica de Terapia Ocupacional: Dominio y Proceso. Barrios Tapia S, Figueroa Burgos C, Hidalgo Beltrán L, Llanos Castro F, Naranjo Figueroa C, Ocampo Alegría N, et al., traductores. 4ª ed. Concepción, Chile: Universidad San Sebastián; 2020. [ Links ]

How to cite: Mena-Gutiérrez P, Pérez-Jara AF, Espinoza-Carrillo I, Kessi-Gutiérrez A, Rueda-Castro L. Experiences of Anticipated Grief in Primary Informal Caregivers from the Metropolitan Region (Chile): Occupational Changes. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados. 2024;13(2):e3929. doi: 10.22235/ech.v13i2.3929

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. P. M. G. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 13; A. F. P. J. in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 13; I. E. C. in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 13; A. K. G. in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 13; L. R. C. in 1, 7, 10, 11, 14.

Received: March 11, 2024; Accepted: August 22, 2024

texto en

texto en