Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.18 no.1 Montevideo 2024 Epub 01-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3333

Original Articles

Emotional intelligence and academic procrastination in university students in Peru

1 Universidad Peruana Unión, Perú

2 Universidad Peruana Unión, Perú

3 Universidad Peruana Unión, Perú

4 Universidad Peruana Unión, Perú, cristianadriano@upeu.edu.pe

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between Emotional Intelligence (EI) and Academic Procrastination (AP) in university students and to generate a predictive model. This study has a quantitative approach and a cross-sectional predictive design. Two hundred fifty-four students from different professional schools in Peru participated, whose ages fluctuated between 18 and 30 years. The Brief Emotional Intelligence Inventory for Seniors (EQ-I-M20) and the Academic Procrastination Scale were administered. The findings show that 52 % of the participants have a high level of emotional intelligence, and 51.2 % have a high level of academic procrastination. The association between emotional intelligence and academic procrastination was significant and negative. The dimensions of emotional intelligence significantly predict academic procrastination, except for the intrapersonal dimension.

Keywords: emotional intelligence; academic procrastination; university students; correlations; predictors; Peru

El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la relación entre la Inteligencia Emocional (IE) y la Procrastinación Académica (PA) en estudiantes universitarios y generar un modelo predictivo. Este estudio tiene un enfoque cuantitativo y de diseño predictivo transversal. Participaron 254 estudiantes, cuyas edades fluctuaron entre los 18 y los 30 años, de distintas escuelas profesionales en Perú. Se administró el Inventario Breve de Inteligencia Emocional para Mayores (EQ-I-M20) y la Escala de Procrastinación Académica. Los hallazgos muestran que el 52 % de los participantes tienen un nivel alto de inteligencia emocional y el 51.2 % un nivel alto de procrastinación académica. La asociación entre la inteligencia emocional y la procrastinación académica fue significativa y negativa. Las dimensiones de la inteligencia emocional predicen significativamente la procrastinación académica, a excepción de la dimensión intrapersonal.

Palabras clave: inteligencia emocional; procrastinación académica; estudiantes universitarios; correlación; predictores; Perú

O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar a relação entre Inteligência Emocional (IE) e Procrastinação Acadêmica (AP) em estudantes universitários e gerar um modelo preditivo. Este estudo tem uma abordagem quantitativa e um desenho preditivo transversal. Participaram 254 alunos, com idades entre 18 e 30 anos, de diferentes escolas profissionais em Peru. Foram aplicados o Inventário Breve de Inteligência Emocional para Idosos (EQ-I-M20) e a Escala de Procrastinação Acadêmica. Os resultados mostram que 52 % dos participantes têm um alto nível de inteligência emocional e 51,2 % um alto nível de procrastinação acadêmica. A associação entre inteligência emocional e procrastinação acadêmica foi significativa e negativa. As dimensões da inteligência emocional predizem significativamente a procrastinação acadêmica, com exceção da dimensão intrapessoal.

Palavras-chave: inteligência emocional; procrastinação acadêmica; universitários; correlações; preditores; Peru

The university stage is essential in students' lives since it allows them to develop knowledge and skills. However, at the same time, it is accompanied by demands that must be met satisfactorily to achieve the proposed goals (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2014). At this stage, other problems related to the educational field appear, such as low academic performance, low self-esteem, academic dropout, and academic procrastination (AP) (Abdi Zarrin et al., 2020). These problems are accompanied by stressful circumstances such as high expectations from their parents, fear of exams, preparation for exhibitions, and obtaining good grades (Cheung et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2015). To cope with these stressful situations, students need to control their emotions better (Ordoñez-Rufat et al., 2021) since these interfere with cognitive processes and allow them to adopt strategies that contribute to the development of coping with different needs or threats (Sánchez et al., 2019). Students need to manage their emotions appropriately, thus allowing them to have control over other aspects: their tasks, the time in which they carry out their activities, and adopt attitudes of empathy and well-being (Ordoñez-Rufat et al., 2021). In this way, university students with high emotional intelligence (EI) will be in better conditions to face the challenges and demands of university education and thus achieve better results (Dominguez-Lara & Campos-Uscanga, 2019).

EI is defined as the ability to recognize, understand, and understand the emotions and feelings of oneself and others and use that information in knowledge to guide one's thoughts and actions (Brackett & Salovey, 2006; Guil et al., 2018; Salovey & Grewal, 2005). In the field of education, emotional intelligence develops two skills. The first refers to recognizing emotions in oneself and one's peers. The second implies that students can use self-knowledge to solve problems and increase interaction in social contexts (Muquis Tituaña, 2022). This means that EI improves mood and allows a person to understand their needs and those of others (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2018). The skills approach points out that EI is the cognitive ability aimed at perception, assimilation, and emotional regulation (Salovey & Mayer, 1990), while the mixed approach is understood as a set of competencies, personal and social skills that affect our ability to adapt and how people perceive their own emotions, as well as those of others, about their environment, taking into account their effectiveness in expressing themselves, relating and getting ahead (Bar-On, 2006). Therefore, if students do not have sufficient socio-emotional strategies to carry out their academic activities, such as identifying, regulating, managing, and controlling their emotions, they will have difficulty organizing, planning, and having control over them, which will lead them to the AP (Estrada et al., 2020; Hen & Goroshit, 2014; Rahimi & Vallerand, 2021; Zhou & Kam, 2016).

Procrastination is the voluntary act of unjustifiably postponing a planned action despite knowing the negative consequences (Hall et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022; Steel & Klingsieck, 2015); within a typology, AP is defined as the behavior of postponing the start and end of activities related to learning; such as reading texts, preparing for exams and preparing assignments (Jin et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022). Also, it is considered a common phenomenon among universities, harming the performance and academic success of students (Grunschel et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018). Regarding prevalence, in Asian students, it is estimated that between 32.7 % and 52.5 % present procrastinating behavior (Lowinger et al., 2016; Tahir et al., 2022), while in Latin American countries, it ranges between 35.05 % and 55.8 % (López-Frías et al., 2021; Wildberger & Aranda, 2022; Zárate et al., 2020), and in a Peruvian context, 48.2 % evidence these behaviors (Estrada et al., 2020). AP is harmful to university students in decision-making, low academic performance, low self-esteem, lack of self-control, academic dropout, low tolerance for frustration (Maria-Ioanna & Patra, 2020; Moreta-Herrera & Durán-Rodríguez, 2018) and mental health problems (Hen & Goroshit, 2014; Nguyen et al., 2013). Students perceiving tasks as heavy, threatening, difficult, boring, or annoying may react by postponing their tasks for fear of failure (Ferrari et al., 1998).

Some theoretical models that explain AP are psychodynamic, which explains that the origin of procrastination occurs in childhood since, at this stage, personality develops; it is based on the concept of avoiding tasks because they are a threat to the ego, that is why this model postulates that procrastination is the fear of not being able to achieve an established goal (Atalaya et al., 2019). On the other hand, the motivational theoretical model indicates that students who procrastinate are unmotivated. That is why they are more likely to delay or postpone the start or progress of their tasks. There is also a third model called behavioral, which mentions that procrastinating behavior persists when it is constantly repeated and is maintained due to its reward effect, which is why those students who have the habit of postponing an activity that takes time to complete and causes them discomfort, they do it for another that implies rapid development with immediate reward (Chan Bazalar, 2011). Finally, the cognitive model indicates that procrastinators process information in a dysfunctional way, and their thought structure is maladaptive since they present negative characteristics of impossibility and fear (Wolters, 2003); procrastination begins with the belief that carrying out some activity is impossible, presenting little tolerance for frustration and resulting in the abandonment or postponement of essential tasks (Álvarez Blaz, 2010).

Studies show that there is a relationship between EI and AP (Clariana et al., 2011; Deniz et al., 2009; Garg et al., 2016; Hen & Goroshit, 2014). However, in Peru, few studies analyze the relationship between these variables; one was conducted on adolescents from the San Martin region, and an inverse relationship was found (Reátegui Ríos et al., 2022). Conducting this research on university students is convenient since it will serve as a basis for other research with the same variables. Likewise, it will allow us to understand how these variables interact in the development and maintenance of various psychological problems and allow the respective areas within the universities to propose better intervention programs to increase emotional intelligence and thus reduce the rates of academic procrastination.

Therefore, the study aimed to analyze the relationship between emotional intelligence and academic procrastination in Peruvian university students.

Materials and Methods

Design

The study was carried out within the framework of a quantitative approach, with an associative strategy called a cross-sectional predictive design (Ato et al., 2013), to explore the functional relationship between emotional intelligence and academic procrastination, which is the information collected at a specific time.

Participants

The sample comprised 254 university students residing in Peru, with ages ranging between 18 and 30 years, who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study by providing their informed consent. The selection of participants was through non-probabilistic convenience sampling (Otzen & Manterola, 2017).

Instruments

Brief Inventory of Emotional Intelligence for Seniors (EQ-I-M20). The instrument was derived from the EQ-i: YV by Bar-On and Parker in 2000 (Pérez et al., 2014) and was adapted to Peruvian university students (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2018). It consists of 20 items that evaluate the five dimensions of EI: intrapersonal, interpersonal, stress management, adaptability, and mood. It has four response options ranging from 1 = it never happens to me to 4 = it always happens to me. The interpretation of the scores is direct for all dimensions except for the stress management dimension, where a high score indicates a lower level of the evaluated behavior. It has adequate validity and reliability indices (ω = .769 - .892; α =.681 - .845), (Dominguez-Lara & Prada-Chapoñan, 2020).

Academic Procrastination Scale. The instrument was developed by Deborah Ann Busko in 1998 among Canadian university students. It was adapted in Peru by Dominguez-Lara et al. (2014) in a university population of Metropolitan Lima. It has 12 items that evaluate two dimensions: procrastination of activities and academic self-regulation. You have five response options, ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. For interpretation, the dimension of procrastination of activities is scored directly; the higher the score, the greater the presence of the evaluated behavior. The opposite occurs with the academic self-regulation dimension, which has an inverted interpretation: the higher the score obtained, the lower the level of said behavior. The scale is valid and reliable (α =.794 - .829) (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2014).

Procedure

Data was collected through virtual forms (Google Forms) sent through a link through their WhatsApp and emails, either personally or through their study groups. The virtual form contained the objective of the study and the informed consent, which indicated their voluntary participation. They could stop answering the questionnaires at any time if they wished. The participant's anonymity and the confidentiality of their data were ensured by checking the box in the questionnaire section. Finally, we were asked to confirm the sociodemographic data before solving the two instruments to measure the EI and AP variables. The information collected was used solely for this study.

Data analysis

First, descriptive analyses of relative and absolute frequencies were carried out to identify the levels of each variable. The skewness and kurtosis coefficients were analyzed to verify the data's normality assumptions, which must be within the range ± 1.0 (Ferrando & Anguiano-Carrasco, 2010), indicating the normal distribution. Subsequently, Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was used to analyze the relationship between the study variables (Akoglu, 2018). Finally, the multiple linear regression statistical model was carried out, which allows us to know the role of emotional intelligence as a predictor of academic procrastination (Ato et al., 2013). All data analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 statistical software.

Ethical considerations

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Unión (Resolution No. 2022-CE-FCS-UPeU-038). Likewise, it has followed the guidelines of the ethical principles of research on human beings of the Declaration of Helsinki. Personal data were treated confidentially and used exclusively for this research. The authors of this research declare that they have no conflict of interest in courses or future ones.

Results

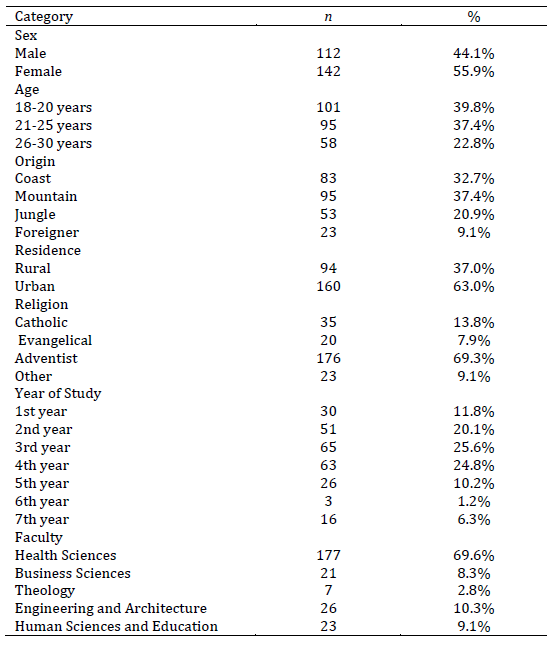

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants; it was found that the majority were women (55.9 %). The age range with the most respondents (39.8 %) is between 18 and 20 years old. About origin, 37.4 % come from the country's mountains. In addition, students who reside in urban areas are 63.0%. Regarding religion, 69.3 % of university students are Seventh-day Adventists. Likewise, 25.6 % are in the 3rd year of their degree. Finally, the faculty with the most participants was health sciences (69.6 %).

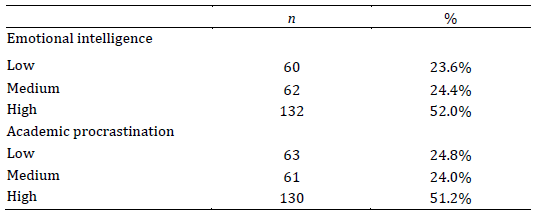

It can be seen in Table 2 that 52.0 % of the participants have a high level of EI, which indicates that the majority have a high capacity to recognize, understand, and adequately manage their emotions. On the other hand, 51.2 % have a high level of AP; that is, their level of self-regulation is low, and they tend to postpone their activities more frequently.

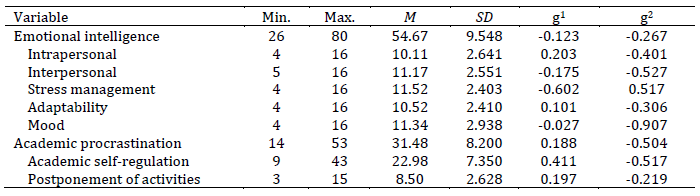

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics such as the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis; the latter is used to analyze the normality of the data. The skewness and kurtosis values of the variables were found within the range ± 1.0 (Ferrando & Anguiano-Carrasco, 2010), indicating that the data follow a normal distribution. These indicators allowed the use of parametric tests such as r of Pearson to test the hypotheses.

Table 3: Descriptive analysis of the variables

Notes: Min.: Minimum; Max.: Maximum; M: Medium; SD: Standard Deviation; g1: Asymmetry; g2: Kurtosis.

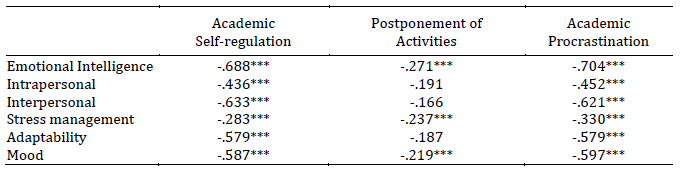

Table 4 shows the correlation between the dimensions of the variables, where a negative and highly significant correlation is perceived between the EI variables and AP (r = -0.704; p < .001). That is, people with a low mood tend to postpone academic activities more frequently. However, the correlations between the interpersonal, intrapersonal, and adaptability dimensions and the dimension of postponement of activities are not significant.

Table 4: Correlations between the dimensions of the variables in the participants

***The relationship is significant at the p < .001 level

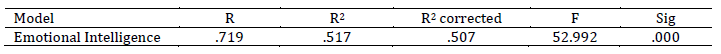

Table 5 shows the determination coefficient R2 = .517; this indicates that emotional intelligence explains 51.7 % of the total variance of the academic procrastination variable. A higher value of the coefficient of determination indicates greater explanatory power of the regression equation and, therefore, greater predictive power of the dependent variable. The F value of ANOVA (F = 52.992, p=<.000) indicates the existence of a significant linear regression between the predictor variable and the academic procrastination variable.

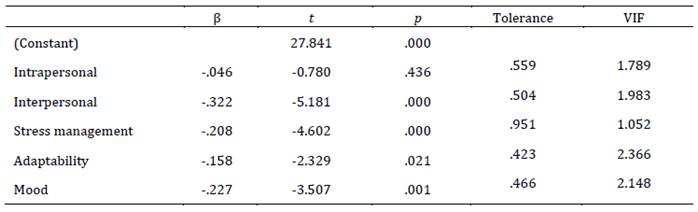

Table 6 shows the multiple linear regression analysis; it was found that most of the dimensions of EI are predictors of PA, such as interpersonal, stress management, adaptability, and mood, with a value of p < .01, except for the intrapersonal dimension, which is not a predictor of BP (p > .05). On the other hand, the VIF values are less than 10, an indicator of the absence of multicollinearity.

Discussion

EI plays an important role in academic success (Chang & Tsai, 2022) facilitating students to adequately manage their emotions, allowing them to control aspects such as their tasks, the time in which they carry out their activities, stress, and adopt attitudes of well-being and empathy (Ordoñez-Rufat et al., 2021). On the other hand, it has been observed that students who have low levels of EI are more likely to procrastinate (Guo et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). This work aimed to determine if there is a relationship between EI and AP in university students.

The results show that EI and its dimensions are negatively correlated with the AP variable (r= -704; p < .001), suggesting that AP levels would be low when EI skills are sufficiently developed (Reátegui Ríos et al., 2022). This means that students who have developed the emotional skills to recognize and manage their emotions tend to experience a greater sense of well-being, which is why they do not postpone activities, prepare for exams, and dedicate time to preparing their homework (Deniz et al., 2009; Frausto et al., 2021). This coincides with empirical studies that relate both variables (Clariana et al., 2011; Deniz et al., 2009; Hen & Goroshit, 2014).

On the other hand, in the linear regression analysis, it was found that EI significantly predicts the AP variable (R2 = 0.517; p =< .000), coinciding with other similar studies, where it is observed that students procrastinate by not having good management of their emotional skills and delay tasks due to the deterioration of their interpersonal relationships (Clariana et al., 2011). Other studies mention that task delay is caused by inadequate management of emotions (Moreta-Herrera & Durán-Rodríguez, 2018; Navarro Roldan, 2016). Likewise, procrastination occurs when students lack motivation (Pardo Bolivar et al., 2014).

Regarding the dimensions of emotional intelligence, it was found that some of them significantly predict AP. The first is the interpersonal dimension, which covers social awareness skills and interpersonal relationships, among others (Brito et al., 2019; Fragoso-Luzuriaga, 2015) which means that inappropriate relationships with friends, family, and teachers can affect procrastinating behavior (Clariana et al., 2011; Gil Flores et al., 2020). Therefore, a good classroom environment is required, and the student needs to engage in satisfying social relationships that can only be achieved through excellent interpersonal skills (Perpiñá Martí et al., 2022). Regarding the stress management dimension that is related to emotional regulation (Navarro Saldaña et al., 2020; Ugarriza Chavez & Pajares Del Aguila, 2005), stress is considered a relevant cause of AP since perceiving academic demands as a stressor agent produces emotional responses characterized by discomfort, thus triggering avoidance or postponement of academic activities (Garcia Frias & González Jaimes, 2022; Moreta Herrera et al., 2018; Orco León et al., 2022). In the same way, the adaptability dimension is the ability to successfully manage change, remain flexible in different situations, provide effective solutions, and solve problems (Mamani Ruiz, 2017; Navarro Saldaña et al., 2020). This shows that students with good strategies in this component consider themselves good at finding solutions to difficulties and solving them effectively; they would not need to procrastinate (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2018; Inga Ávila et al., 2022; Perpiñá Martí et al., 2022). Finally, the mood dimension involves motivation, optimism, and happiness to cope with academic life (Fragoso-Luzuriaga, 2015). BP causes it. This means that if the student finds sufficient motivation and their interests are covered, procrastination decreases (Angarita Becerra, 2014; Osiurak et al., 2015). However, the dimension that does not predict academic procrastination in this study is intrapersonal (p < .436), unlike other research where it was found that the lack of assertiveness and confidence are essential factors for procrastinating behavior (López-Frías et al., 2021; Parada & Schulmeyer, 2021).

This study has some limitations. One limitation is the size and type of non-probabilistic convenience sampling because the results cannot be generalized; it is recommended to expand the sample size under probabilistic selection. Another limitation is the use of self-report measures that could generate social desirability in the participants. Therefore, it is recommended that the research be completed with semi-structured interviews. Finally, the cross-sectional study is another limitation; longitudinal studies are necessary to analyze the variables' influence over time.

In conclusion, despite the limitations, this study reveals the first empirical evaluation of the predictive model of EI on AP in university students in a Peruvian context. In this framework, the study's results demonstrate that EI plays a fundamental role in predicting BP in university students.

REFERENCES

Abdi Zarrin, S., Gracia, E., & Paixão, M. P. (2020). Prediction of academic procrastination by fear of failure and self-regulation. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 20(3), 34-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2020.3.003 [ Links ]

Akoglu, H. (2018). User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(3), 91-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001 [ Links ]

Álvarez Blaz, O. R. (2010). Procrastinación general y académica en una muestra de estudiantes de secundaria de Lima metropolitana. Persona, 13, 159-177. [ Links ]

Angarita Becerra, L. D. (2014). Algunas relaciones entre la procrastinación y los procesos básicos de motivación y memoria. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología: Ciencia y Tecnologia, 7(1), 91-101. https://doi.org/10.33881/2027-1786.rip.7108 [ Links ]

Atalaya Laureano, C., & García Ampudia, L. (2019). Procrastinación: revisión teórica. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 22(2), 363-378. http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v22i2.17435 [ Links ]

Ato, M., López, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicologia, 29(3), 1038-1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511 [ Links ]

Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18(1), 13-25. [ Links ]

Brackett, M. A., & Salovey, P. (2006). Measuring emotional intelligence with the Mayer-Salovery-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Psicothema, 18(supl.), 34-41. [ Links ]

Brito, D., Santana, Y., & Pirela, G. (2019). El Modelo de Inteligencia Emocional de Bar-On en el Perfil Académico-Profesional de la FACO/LUZ. Ciencia Odontológica, 16(1), 27-40. [ Links ]

Chan Bazalar, L. A. (2011). Procrastinación académica como predictor en el rendimiento académico en jovenes de educación superior. Temática psicológica, 7(1), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.33539/tematpsicol.2011.n7.807 [ Links ]

Chang, Y. C., & Tsai, Y. T. (2022). The effect of university students’ emotional intelligence, learning motivation and self-efficacy on their academic achievement-online English courses. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.818929 [ Links ]

Cheung, D. K., Tam, D. K. Y., Tsang, M. H., Zhang, D. L. W., & Lit, D. S. W. (2020). Depression, anxiety and stress in different subgroups of first-year university students from 4-year cohort data. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274(March), 305-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.041 [ Links ]

Clariana, M., Cladellas, R., Badia, M. D. M., & Gotzens, C. (2011). La influencia del género en variables de la personalidad que condicionan el aprendizaje : inteligencia emocional y procrastinación académica. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 14(3), 87-96. [ Links ]

Deniz, M. E., Traş, Z., & Aydoǧan, D. (2009). An investigation of academic procrastination, locus of control, and emotional intelligence. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri, 9(2), 623-632. [ Links ]

Dominguez-Lara, S., & Campos-Uscanga, Y. (2019). Estructura interna de una medida breve de inteligencia emocional en estudiantes mexicanos de ciencias de la salud. Educacion Medica, 22(December), 262-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2019.10.010 [ Links ]

Dominguez-Lara, S., Merino-Soto, C., & Gutiérrez-Torres, A. (2018). Estudio estructural de una medida breve de inteligencia emocional en adultos: El EQ-i-M20. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación - e Avaliação Psicológica, 49(4), 5-21. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.21865/RIDEP49.4.01 [ Links ]

Dominguez-Lara, S., & Prada-Chapoñan, R. (2020). Invariance in measurement and normative data in a brief measure of emotional intelligence in Peruvian university students. Anuario de Psicologia, 50(2), 87-97. https://doi.org/10.1344/anpsic2020.50.8 [ Links ]

Dominguez-Lara, S., Villegas-García, G., & Centeno-Leyva, S. B. (2014). Procrastinación académica: validación de una escala en una muestra de estudiantes de una universidad privada. Liberabit, 20(2), 293-304. [ Links ]

Estrada Araoz, E. G., & Mamani Uchasara, H. J. (2020). Procrastinación académica y ansiedad en estudiantes universitarios de Madre de Dios, Perú. Apuntes Universitarios, 10(4), 322-337. https://doi.org/10.17162/au.v10i4.517 [ Links ]

Ferrando, P. J., & Anguiano-Carrasco, C. (2010). El análisis factorial como técnica de investigación en psicología. Papeles del Psicologo, 31(1), 18-33. [ Links ]

Ferrari, J. R., Keane, S. M., Wolfe, R. N., & Beck, B. L. (1998). The antecedents and consequences of academic excuse-making: Examining individual differences in procrastination. Research in Higher Education, 39(2), 199-215. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018768715586 [ Links ]

Fragoso-Luzuriaga, R. (2015). Inteligencia emocional y competencias emocionales en educación superior ¿un mismo concepto? Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 6(16), 110-125. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2015.16.154 [ Links ]

Frausto Martín del Campo, A., & Patiño Domínguez, H. A. M. (2021). Afectividad de normalistas: estudio sobre el estado de ánimo y la inteligencia emocional. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 51(3), 45-70. https://doi.org/10.48102/rlee.2021.51.3.390 [ Links ]

Garcia Frias, J., & González Jaimes, E. I. (2022). El estrés académico causante de la procrastinación en la educación virtual . Una revisión sistemática. Revista Ineroamericana para la investigación y el desarrollo educativo, 13(25). https://doi.org/doi.org/10.23913/ride.v13i25.1238 [ Links ]

Garg, R., Levin, E., & Tremblay, L. (2016). Emotional intelligence: impact on post-secondary academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 19(3), 627-642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9338-x [ Links ]

Gil Flores, J., De Besa Gutiérrez, M. R., & Garzón Umerenkova, A. (2020). ¿Por qué procrastina el alumnado universitario? Análisis de motivos y caracterización del alumnado con diferentes tipos de motivaciones. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(1), 183-200. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.344781 [ Links ]

Grunschel, C., Patrzek, J., & Fries, S. (2013). Exploring reasons and consequences of academic procrastination: An interview study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(3), 841-861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0143-4 [ Links ]

Guil, R., Mestre, J. M., Gil-Olarte, P., De La Torre, G. G., & Zayas, A. (2018). Desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional en la primera infancia: una guía para la intervención. Universitas Psychologica, 17(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.11144/Ja [ Links ]

Guo, M., Yin, X., Wang, C., Nie, L., & Wang, G. (2019). Emotional intelligence a academic procrastination among junior college nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(11), 2710-2718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14101 [ Links ]

Gupta, S., Choudhury, S., Das, M., Mondol, A., & Pradhan, R. (2015). Factors causing stress among students of a medical college in Kolkata, India. Education for Health: Change in Learning and Practice, 28(1), 92-95. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.161924 [ Links ]

Hall, N. C., Lee, S. Y., & Rahimi, S. (2019). Self-efficacy, procrastination, and burnout in post-secondary faculty: An international longitudinal analysis. PLoS One, 14(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226716 [ Links ]

Hen, M., & Goroshit, M. (2014). Academic procrastination, emotional intelligence, academic self-efficacy, and GPA: A comparison between students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(2), 116-124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219412439325 [ Links ]

Inga Ávila, M. F., Churampi Cangalaya, R. L., & Vicente Ramos, W. E. (2022). Procrastinación académica en la resolución de problemas de estudiantes universitarios. Revista Conrado, 18(89), 404-411. [ Links ]

Jin, H., Wang, W., & Lan, X. (2019). Peer attachment and academic procrastination in Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of future time perspective and grit. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02645 [ Links ]

Li, C., Hu, Y., & Ren, K. (2022). Physical activity and academic procrastination among Chinese university students: A parallel Mediation Model of Self-Control and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106017 [ Links ]

Liu, G., Cheng, G., Hu, J., Pan, Y., & Zhao, S. (2020). Academic Self-Efficacy and Postgraduate Procrastination: A Moderated Mediation Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1752. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01752 [ Links ]

López-Frías, M.-F., González-Angulo, P., López-Cocotle, J.-J., Camacho-Martínez, J. U., & Ramón-Ramos, A. (2021). Procrastinación académica en estudiantes de enfermería de una Universidad de México. Revista Electrónica en Educación y Pedagogía, 5(9), 57-67. https://doi.org/10.15658/rev.electron.educ.pedagog21.11050905 [ Links ]

Lowinger, R. J., Kuo, B. C. H., Song, H. A., Mahadevan, L., Kim, E., Liao, K. Y. H., Chang, C. Y., Kwon, K. A., & Han, S. (2016). Predictors of academic procrastination in asian international college students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 53(1), 90-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2016.1110036 [ Links ]

Mamani Ruiz, T. H. (2017). Efecto de la adaptabilidad en el rendimiento académico. Centro Psicopedagógico y de Investigación en Educación Superior, 2(1), 38-44. [ Links ]

Maria-Ioanna, A., & Patra, V. (2020). The role of psychological distress as a potential route through which procrastination may confer risk for reduced life satisfaction. Current Psychology, 41(5), 2860-2867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00739-8 [ Links ]

Moreta-Herrera, R., & Durán-Rodríguez, T. (2018). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Procrastinación Académica (EPA) en estudiantes de psicología de Ambato, Ecuador. Salud & Sociedad, 9(3), 236-247. https://doi.org/10.22199/s07187475.2018.0003.00003 [ Links ]

Moreta Herrera, R., Durán Rodríguez, T., & Villegas Villacrés, N. (2018). Regulación Emocional y Rendimiento como predictores de la Procrastinación Académica en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Psicología y Educación - Journal of Psychology and Education, 13(2), 155-166. https://doi.org/10.23923/rpye2018.01.166 [ Links ]

Muquis Tituaña, K. (2022). Inteligencia emocional (Salovey y Malovey) y aprendizaje social en estudiantes universitarios: Emotional Intelligence (Salovey and Malovet) and social learning in university students. RES NON VERBA REVISTA CIENTÍFICA, 12(2), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.21855/resnonverba.v12i2.654 [ Links ]

Navarro Roldan, C. P. (2016). Rendimiento académico: una mirada desde la procrastinación y la motivación intrínseca. Katharsis, 21(1), 241-271. https://doi.org/10.25057/25005731.623 [ Links ]

Navarro Saldaña, G., Flores-Oyarzo, G., & González Navarro, M. G. (2020). Construcción y Estudio psicométrico de un instrumento para evaluar inteligencia emocional en estudiantes chilenos. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 19(39), 29-43. https://doi.org/10.21703/rexe.20201939navarro2 [ Links ]

Nguyen, B., Steel, P., & Ferrari, J. R. (2013). Procrastination’s impact in the workplace and the workplace’s impact on procrastination. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 21(4), 388-399. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12048 [ Links ]

Orco León, E., Huamán Saldívar, D., Ramírez Rodríguez, S., Torres Torreblanca, J., Figueroa Salvador, L., R. Mejia, C., & Corrales Reyes, I. E. (2022). Asociación entre procrastinación y estrés académico en estudiantes peruanos de segundo año de medicina. Revista Cubana de Investigaciones Biomedicas, 41(1), 1-15. [ Links ]

Ordoñez-Rufat, P., Polit-Martínez, M. V., Martínez-Estalella, G., & Videla-Ces, S. (2021). Emotional intelligence of intensive care nurses in a tertiary hospital. Enfermería Intensiva (English ed .), 32(3), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfie.2020.05.001 [ Links ]

Osiurak, F., Faure, J., Rabeyron, T., Morange, D., Dumet, N., Tapiero, I., Poussin, M., Navarro, J., Reynaud, E., & Finkel, A. (2015). Déterminants de la procrastination académique : motivation autodéterminée, estime de soi et degré de maximation. Pratiques Psychologiques, 21(1), 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prps.2015.01.001 [ Links ]

Otzen, T., & Manterola, C. (2017). Técnicas de muestreo sobre una población a estudio. International Journal of Morphology, 35(1), 227-232. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022017000100037 [ Links ]

Parada, B. E., & Schulmeyer, M. K. (2021). Procrastinación académica en estudiantes universitarios. Aportes, 30, 51-66. [ Links ]

Pardo Bolivar, D., Perilla Ballesteros, L., & Salinas Ramírez, C. (2014). Relación entre procrastinación académica y ansiedad-rasgo en estudiantes de psicología. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 14(1), 31-44. [ Links ]

Pérez, M. del C., Gázquez, J. J., Rubio, I. M., & Molero, M. del M. (2014). Inventario breve de inteligencia emocional para mayores (EQ-i-M20). Psicothema, 26(4), 524-530. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.166 [ Links ]

Perpiñá Martí, G., Sidera Caballero, F., & Serrat Sellabona, E. (2022). Rendimiento académico en educación primaria: relaciones con la inteligencia emocional y las habilidades sociales. Revista de Educacion, 395, 291-319. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-395-515 [ Links ]

Rahimi, S., & Vallerand, R. J. (2021). The role of passion and emotions in academic procrastination during a pandemic (COVID-19). Personality and Individual Differences, 179(May), 110852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110852 [ Links ]

Reátegui Ríos, R., Tarrillo Montenegro, D., Córdova Saavedra, F., & Ramírez Vega, C. (2022). Inteligencia emocional y procrastinación académica en estudiantes del nivel secundario de Tarapoto, perú - 2021. Revista Científica de Ciencias de la Salud, 2(15), 33-42. https://doi.org/10.17162/rccs.v2i15.1891 [ Links ]

Salovey, P., & Grewal, D. (2005). The science of emotional intelligence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(6), 281-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00381.x [ Links ]

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211. https://doi.org/10.2190/dugg-p24e-52wk-6cdg [ Links ]

Sánchez, R. A., Osornio, C. L., & Ríos, S. M. R. (2019). Habilidades sociales básicas y su relación con la ansiedad y las estrategias de afrontamiento en estudiantes de medicina. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 22(2), 834-856. [ Links ]

Steel, P., & Klingsieck, K. B. (2015). Procrastination. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition, 19, 73-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25087-3 [ Links ]

Tahir, M., Yasmin, R., Butt, M. W. U., Gul, S., Aamer, S., & Naeem, N. (2022). Exploring the level of academic procrastination and possible coping strategies among medical students. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 72(4), 629-633. https://doi.org/10.47391/JPMA.0710 [ Links ]

Ugarriza Chavez, N., & Pajares del Aguila, L. (2005). La evaluación de la inteligencia emocional a través del inventario de BarOn ICE: NA, en una muestra de niños y adolescentes. Persona, 8, 11-58. https://doi.org/10.26439/persona2005.n008.893 [ Links ]

Wang, Q., Kou, Z., Du, Y., Wang, K., & Xu, Y. (2022). Academic procrastination and negative emotions among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating and buffering effects of online-shopping addiction. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(February), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.789505 [ Links ]

Wildberger, C., & Aranda, M. (2022). Procrastinación académica en la modalidad virtual en estudiantes de carreras de salud en un centro universitario . Periodo 2022. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6, 6721-6731. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i6.3917 [ Links ]

Wolters, C. A. (2003). Understanding procrastination from a self-regulated learning perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 179-187. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.179 [ Links ]

Zárate, N., Flores, P., Achoy, L., & Ramos, M. (2020). Procrastinación académica en estudiantes de medicina. Sinergias Educativas, 5, 252-259. https://doi.org/10.37954/se.v5i2.135 [ Links ]

Zhang, Y., Dong, S., Fang, W., Chai, X., Mei, J., & Fan, X. (2018). Self-efficacy for self-regulation and fear of failure as mediators between self-esteem and academic procrastination among undergraduates in health professions. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23(4), 817-830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-9832-3 [ Links ]

Zhou, M., & Kam, C. C. S. (2016). Hope and General Self-efficacy: Two Measures of the Same Construct? Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 150(5), 543-559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2015.1113495 [ Links ]

How to cite: Chavez-Fernandez, S., Haro-Rodriguez, Y. M., Machaca-Calcina, L. G., & Adriano-Rengifo, C. E. (2024). Emotional intelligence and academic procrastination in university students in Peru. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3286. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3286

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing. S. C. F. has contributed in 1,4, 6, 7, 11, 12; Y. M. H. R. in 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12; L. G. M. C. in 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12; C. A. R. in 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13.

Received: April 28, 2023; Accepted: May 03, 2024

texto en

texto en