Introduction

Although it has come to be considered a minor art form in Uruguay1, the illustration sector is undergoing a consolidation process. Beyond possible biases against mass-produced or commercial arts, the illustration profession offers a tangible means for artists to earn a living. Hence, in the face of a small market and a still fragile marketing system, the sector has been fostered by supporting public policies both in the fields of visual arts and cultural industries. The indefinite cancellation of presential activities during the pandemic has also forced artists to make innovations that have had positive impacts on the strengthening of the system in the longer term. The absence of preliminary studies, however, hinders a thorough analysis of this phenomenon, on which it is still necessary to establish a benchmark that would allow us to confirm possible hypotheses in a definitive manner. This is especially relevant, moreover, in view of the rapid advent of artificial intelligence and the eventual reconfiguration of both the artistic process and the labor market linked to this activity. Commercially, the supports and objects connected to graphic arts were expanded, promoting a greater professionalization and creating market niches independent of the galleries and large publishing houses. But the links among members of the art community were also consolidated, gathered around a common objective of “resistance” that strains the balance between the functional and social aspects of the discipline.

To help reverse this situation, this article presents the historical background of the illustration sector in Uruguay and describes some of the phenomena which are observed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic through the survey of available information and the conduction of semi-structured interviews with artists and qualified informants. 2 The text is structured in the following sections: background (historical antecedents), public policies and spaces of resistance (policy instruments and social actions affecting this art), the illustration sector (main characteristics of this market), impacts and opportunities of the pandemic (observed facts and trends), and final remarks on a possible future scenario. Its main conclusions indicate that -the anchored in a solid artistic tradition - artists are seeking new subsistence opportunities, creating market niches and making use of several platforms and media. However, there are important structural weaknesses surrounding the social, professional and economic status of artists, as well as of updated information on the opportunities and challenges in terms of the activity linked to cultural industries and the possibility of internationalization of local artistic production.

Background

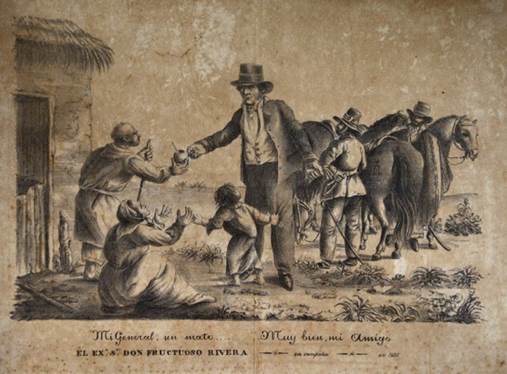

As the art to tell a story through graphic symbols,3 the origins of Uruguayan illustration may be linked to the beginnings of the national artistic practice, assuming different roles4 and covering a broad range of visual artistic expressions5 over time. The inauguration in 1830 of the first lithography studios allowed for the documentation of customs, the artistic representation of landscape and historical themes, and the French-style academic allegory.6 A graphic tradition with a strong artisan character was initiated at this stage, where the roles of symbol, emblem and device designer, calligrapher, decorator and graphic reporter of the life and idiosyncrasy of the time converged. The technique was also used by some artists for the illustration of newspapers and magazines, as well as in the creation of prints on ephemeris and important events in the new republic (Figure 1). In general, these images had an essentially communicative function, in which the accompanying texts provided the essential context for their understanding.7

Figure 1 Juan Manuel Besnes e Irigoyen, "Mi general... un mate. Muy bien mi amigo. El Excelentísimo Señor Don Fructuoso Rivera en campaña", 1838, lithography on paper, 43,3 x 41,7 cm, Museo Histórico Nacional.

In the late 19th Century engraving “gradually and imperceptibly lost artistic hierarchy in the scale of social worth, when it was almost exclusively devoted to the service of publicity monograms and commercial labels”.8 But in the early decades of the 20th Century, this trend somehow managed to be reverted in the editorial field, where some of the experiences connected to the European vanguards were channeled.9 During those years, magazines such as Pegaso (1918-1924), Los Nuevos (1920-1921), La Pluma (1927-1931), Vanguardia (1928), Cartel (1929-1931), Alfar (1926-1955) and La Cruz del Sur (1924-1931)10 became the quintessential mass media of cultural activity11 and renowned local painters actively contributed in book illustration, as well as in graphic press, caricature, poster and theater set design.12

One of the most outstanding cases, in this sense, is that of the master Rafael Barradas (1890-1929), "an artist open to almost all manifestations of the plastic arts, since he did not restrict himself only to painting, but also embarked on illustration for the graphic press, theater stage design, posters, caricature and illustration of children's books" (Figure 2). But among the other artists who ventured into illustration are also José Lanzaro,13 Adolfo Pastor,14 Adolfo Halty Dube,15 Amalia Nieto,16 Mario Radaelli,17 Nerses Ounanian,18 José María Pagani,19 María Rosa de Ferrari,20 José Costigliolo,21 Eduardo Vernazza,22 Leonilda González,23 Carlos Fossatti,24 Claudio Silveira Silva,25 Lincoln Presno and Raúl Pavlotzky.26 In addition to cases such as those of Manuel Domínguez Nieto,27 Andrés Feldman,28 Eduardo Larrarte,29 Mario Spallanzani,30 Roberto Garino,31 Carlos Páez Vilaró32; Euridice Méndez de Cruz,33 Manuel López Cortés,34 Adolfo Montiel,35 Carlos Lombardo36 and Hugo O´Neill Hamilton37.

In turn, the draftsmen and typesetters of the printers carried out the task of graphic design, employing resources such as “lettering”, futuristic and Bauhaus typography, and the techniques of woodcutting and linocutting, which made it possible to highlight the figures and create full and simple forms, consistent with the taste of the time. In fact, woodcutting significantly contributed to the consolidation of the Uruguayan cultural field from the 1920s onwards. Its images worked as references of social cohesion among writers and visual artists until the late 1960s, generally in connection to the literature of the time and the narratives linked to social criticism. As argued by Gabriel Peluffo Linari,38 in most cases xylographic practice was cultivated as a strongly illustrative discipline, subsidiary to historical, literary, political or aesthetic-doctrinarian narratives, and in connection to a kind of figuration framed within social realism.

It is only in the early seventies that drawing and the various forms of printmaking processes occupied a prominent place as an autonomous, and often exclusive manifestation of a great number of artists. This was a time of great "editorial and graphic frenzy among authors, readers and publishers" in which many publishing houses were founded and numerous weeklies and magazines were published on an almost weekly basis and with a remarkable thematic and authorial diversity. The intense political activity also generated an enormous amount of graphic work and "the theatrical groups, the national publishing houses, the annual presence of the Book and Engraving Fair, represented innumerable opportunities for visual communication”.39

Institutions such as the National School of Fine Arts or the Engraving Club had an intense activity through the production of posters and the development of graphic techniques. As in other countries in the region, graphic initiatives of a collective nature were developed that rose awareness of the different social demands, in politically oppressive contexts of urgency, "articulating strategies of transformation and resistance that radically changed the ways of doing, the ways of establishing intersubjective links, of building communities and even the very circulation of graphic supports". These materials - characterized as much by the precariousness of their components and media as by their graphic and distribution potential - circulated outside the field of art, evidencing the variety of graphic action tools that connect modes of vindication and dissidence at an international level..

Although this momentum was attenuated during the process of institutional rupture that took place between 1973 and 1985, in those years drawing also experienced a brief and rapid flourishing that broke with some of the predominant naturalistic tendencies of the 19th century.40 Initially, these manifestations were mainly expressionist and achromatic, with an often “monstruous” and very detailed figuration, to later give way to a broader field of personal languages and styles. In every case, however, they shared a high technical and aesthetic level, as well as a strongly antiestablishment character, in the sense of the use of new codes to express contents linked to the social environment. As described by Jorge Abbondanza: “the plastic artist thus became a messenger, rendering his tools in the service of an allusive function and a metaphoric reach that accompanied the -certainly infuriated- moods the people experienced on the street, as the country faced more and more tension and could be headed to a multiple crisis (political, economic, social, cultural), from which it would emerge laboriously a long decade later”.41

Figure 2 Rafael Barradas, Study, c.1918, watercolor and pencil, paper, 23 x 32 cm, National Museum of Visual Arts (Inventory No.: v).

Those years also saw a shift in the field of engraving, which began to move towards lyric figuration, emphasizing a poetics of subjectivity with new experimental resources. In general, there was a greater use of intaglio engraving and techniques such as silkscreen printing, relief engraving and the mechanical reproduction of offset drawings. Additionally, there appears a new type of non-illustrative production, of strong plastic-visual nature, which opposes the main trend, prone to illustration and drawing as tributaries of graphic design (Figure 2).42

With the return of democracy, however, there was a process of “renovation” of the visual arts, which caused a detachment of the new generations of artists with the tradition of the great local masters. As Peluffo Linari explains, in this “wiping the slate clean” the aim was not to represent politics in art or try to respond to the social distress, but to create discourse strategies which, in themselves, constituted a political problem. There was, then, a great need to redefine identities, memories and territories that resulted from diverse cultural appropriations, which led to a marked interest in experimentation and the crossing of languages, the allegorical narrative support, and the use of the spectator’s real space and time.43 However, the critic argues that the visual arts also then began to underestimate their possibilities for renewing the forms of social reflection in the symbolic field, promoting the creation of an interpretative community closed in on itself, as well as a latent state of “rumination”, which paralyzed the attempts at cultural transformation, affecting both the politics of representation and the relationship between production and reception of contemporary art.

Public policies and spaces of resistance

In terms of public policy, the first measures connected to the illustration sector refer to the organization of the Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Salon). The event incorporated, since its inauguration in 1937, a “Drawing and Engraving Award”, and, since 1946, an “Illustration Award” which was maintained until 1966 under the categories “Award for the illustration of published book” and “Award for the illustration of unpublished book”. It is in 1967, in the frame of the XXXI National Salon of Fine Arts, that awards are unified with the purpose of overcoming the traditional (and now outdated) dichotomy between major and minor arts. But in 2014, the specific promotion of the sector was resumed again with the creation of the National Illustration Award for Children’s and Young People’s Literature for unpublished works.

This award is transformed once again into the Illustration Award through the incorporation of the categories “single Illustration” (2019) and “animated video-illustration” (2021). But in its latest edition (2023), it once again overcomes the distinctions between categories and artistic techniques by awarding two general illustration prizes. It maintains, however, a specific award for the promotion of animated video illustration, which is granted in collaboration with the Uruguayan Film and Audiovisual Agency (ACAU) in the framework of its actions to stimulate the production of national audiovisual works and projects. It also considers that artists must declare the use of artificial intelligence tools as an artistic technique, requesting information on the software used as well as on the copyright of the databases used in the creative process. Although controversial, this incorporation is the first experience of its kind in the framework of a state and national artistic summons, which will make it possible to gather information that will feed the subsequent development of eventual regulatory frameworks for the sector.

From the National Directorate of Culture of the Ministry of Education and Culture, this type of measures has been accompanied by initiatives to promote the participation of Uruguayan illustrators in the foreign commercial markets and circuits Through the Department of Creative Industries, with the support of Uruguay XXI - - the agency responsible for the promotion of exports, investments and country image - their participation has been fostered in relevant international events such as: the Buenos Aires International Book Fair, the Guadalajara International Book Fair, the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, the Shanghai International Book Fair, the Nami Island International Picture Book Illustration Concours (Korea), the Golden Pinwheel Young Illustrators Competition Award (China), the Iberoamérica Ilustra (Mexico), The Gran Salòn México, Imaquinario (Peru) and Iridka (Spain). Support was also given to activities in the framework of exhibition and commercial agreements connected with editorial development, such as those organized by the Cámara Uruguaya del Libro (Uruguayan Book Chamber), a civil organization that holds the International Book Fair since 1978 and organizes the literature contest Bartolomé Hidalgo Award since 1988.

These policies have, in general, strengthened the visibility of authorial work and illustration as an artistic discipline which borders and connects strongly with other areas of the visual arts and visual communication Unfortunately, however, there are no systematized data on the characteristics and impacts of this type of initiatives, which so far are developed as specific activities outside of a policy or strategy capable of overcoming the different periods of government.

Neither has there been continuity in specialized education.44 The Círculo de Bellas Artes (1905) and the Escuela de Artes y Oficios (1915) trained many of the first "commercial artists" who worked in printing and publishing houses during the first decades of the 20th century. In the forties, the National School of Fine Arts was founded (1943) and initiatives oriented towards the professionalization of "draftsmen" appeared, such as the School of Commercial Arts of the agency Publicidad Oriental and the courses of "Commercial Advertising" and "Graphic Arts" of the Universidad del Trabajo del Uruguay. For a long time, there were also training options such as correspondence courses and those dictated in private academies or by different professionals in their private workshops..

In fact, besides the incentives to artists deployed by private sponsorships and international organizations, the emergence of specific training in design took place. In the midst of the process of democratic reconstruction, the inauguration of the first training center in the field responded to the problem of activating the national industrial production, finding a solution that at the same time met the local needs.45 It was not until 1993 that the first Bachelor's Degree in Graphic Design was founded (Universidad ORT Uruguay), which in 2002 was followed by the Graphic Design option in the Bachelor's Degree in Arts at the National School of Fine Arts Institute (Universidad de la República) and later by the Bachelor's Degree in Visual Communication at the current School of Architecture, Design and Urbanism of the same university (2009), and the Bachelor's Degree in Graphic Design at the Universidad de la Empresa (2009). 46.

To this day, however, illustration lacks specific academic training or academic research that addresses the subject from the fields of art history and humanities. At the moment, the only publications refer to the catalogs of the Illustration Award and the coverage of illustration practitioners by the National Institute of Visual Arts in 2022.47 Nor has there been any theoretical material produced on the discipline of graphic design in the country, which - despite some occasional efforts 48 - "has a scarce specialized bibliography at the local level, the absence of an ad hoc institutional space and an almost non-existent ordered and classified documentary reservoir".49 Despite the creation in 2008 of the Center and Archive of Graphic Design and Advertising, under the Ministry of Education and Culture (Law 18.362, Art. 309), it is still necessary to "fill in the gaps in this body of knowledge" and "learn and record who is who in the construction of identities, of unique and unrepeatable references, of essential anchor points”.50

Historically, there have also existed in the civil society associative initiatives of national, popular, and parastatal nature, which advocated an “independent culture” in the literary, cinematographic, musical, theater and plastic fields.51 Among these experiences, the Club del Grabado de Montevideo (Montevideo Engraving Club), founded in 1953 and whose public life lasted for approximately forty years, stands out. Tributary of the Mexican experience of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Workshop) and of the printmaking clubs of Porto Alegre and Bagé (Brazil), this group operated as a “graphic platform” which sought to popularize the practice and which -like other Latin American experiences-had in fact a vindicatory intention of the “proletarian public sphere”.52. During the dictatorship (1973-1985), the Club del Grabado operated as an enclave for the deliberation on and resistance to the collective and symbolic discourses that dominated the official public sphere. Although in the sixties its image production had come closer to drawing, in those years it was characterized by the predominance of the syntactic logic of the poster and the emergence of a figuration of high contrasts and formal definition. There was also a clear preeminence of resources such as the representation of ties, seals, adhesive tapes and other elements of closure or concealment, as well as the use of torn or fissured full spots as an allegory of cracking.53

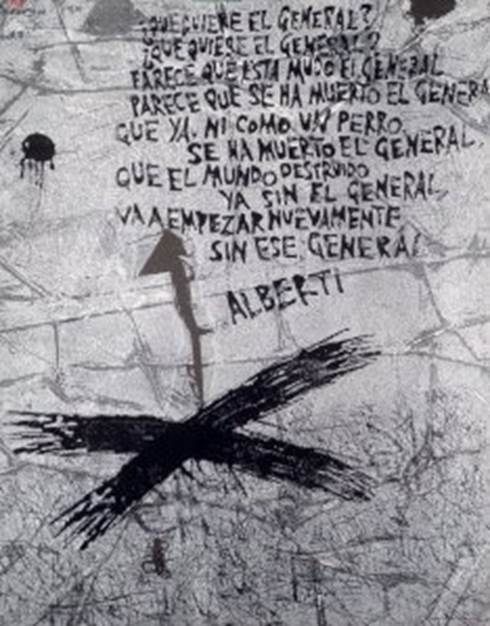

Figure 3 Antonio Frasconi, WALL II - Alberti, 1962, engraving, 60 x 76 cm, National Museum of Visual Arts (Inventory No.: 4932).

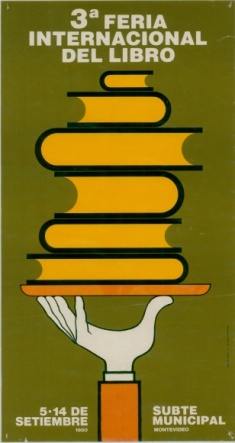

Another enclave for the resisting graphic art was the “Feria Nacional de Libros, Grabados, Dibujos y Artesanías” (National Fair of Books, Engravings, Drawings and Crafts) (1960-2006) (later “Feria del Libro” / Book Fair) organized by a group of artists and intellectuals with the aim of supporting the Uruguayan authors and editions.54 Like the Club del Grabado, this space worked as an anti-dictatorship militant environment which questioned the reference system of traditional representation, promoting the search for new forms of expression. With a constant concern for the material aspects of edition, the fair established a crossover between the arts and a special balance between literature and the plastic arts, with which it was identified into the 21st Century (Figure 4).55 Its startup coincided, also, with the launch of the illustrated poetry magazine, which would later become the publishing company 7 Poetas Hispanoamericanos (7PH) (7 Spanish-American Poets), which proposed a clear aesthetic posture towards poetry creation (Figure 3).

Figure 4 Poster for the 3a. Feria Internacional del Libro (1980), Colecciones Digitales, Biblioteca Nacional.

In a context of increasing social conflict, these initiatives brought together many members of the Uruguay Engraving Club, the School of Fine Arts and the independent theater groups, fostering spaces of dialogue and exchange networks among intellectuals and artists. However, the restrictions imposed as of 1973 and the State’s repressive measures - raided warehouses, burnt books, imprisonments and exiles - made it difficult for them to survive, seriously affecting the cultural work and artistic production. It was not until the return of democracy that many of these projects were resumed once again, although most of the artistic practices carried out in the seventies and eighties did not have an ample diffusion and had few opportunities for the exchange of experiences due to the situation of isolation and control produced by the political reality.56

Currently, in the specific field of graphic art, spaces of resistance are not necessarily associated to political groups, organizations or institutions, but are articulated through individual voices which are channeled and amplified through means such as personal computers, home printers, mobile phones and social networks with their own internet connections. This kind of graphic action - of hyper-individualized characteristics or of “do it yourself” --- often complements the editorial or commercial activities, circulating a multiplicity of messages of powerful visual impact which vindicate rights, bring causes to light, and propose exercises of memory and argumentations which question or denounce the status quo (Figure 5). There are also initiatives that delve into the ethical question and the social responsibility involved in the trade, in the frame of social communication. In these cases, illustrators address the role of art as a tool to deal with specific problems connected with development or especially complex social, political and cultural issues, such as gender, mental health, digital violence, communication of science and technology, visual journalism and measures in the frame of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The illustration sector

The Uruguayan art market is of very small dimensions if compared to large international centers like London or New York, and is also less dynamic in terms of the appearance and acceptance of new artists. However, in recent years there has been a growing trend whose analysis has been completely left out of the agenda of economic discipline, since there are virtually no technical studies in the area or models that account for its behavior.57 In the specific case of illustration, besides, it is possible to argue that there has been a strong development, not only in connection with the publishing sector, but together with others of more recent impulse, such as videogames, audiovisual production, and urban art.

Despite the absence of updated data, it is also possible to state that there is a greater naturalization of its language by the public, who have become used to seeing it in the press, the virtual media, television and street posters. We have not yet reached the point where people fully value authorship, the work process behind every piece or the fact that the artist is Uruguayan, and there also persist challenges in terms of the tension between art and function (Pintos 2020). In spite of this, as argued by Darío Marroche, organizer of “Microutopías - Feria de Arte Impreso de Montevideo” (Micro-utopias - Montevideo Printed Art Fair) (http://microutopias.press), there is a revaluation of its importance at the communicational level and a greater sense of belonging and identification of the sector.58

This has also been clearly described by leading figures like Carolina Curbelo, who has been boosting the scopes of Uruguayan design for 11 years, from her blog “Mirá Mamá” (www.miramama.com.uy): “many good things have happened since 2010 (…): the Uruguayan Chamber of Design was created; La Pasionaria, a local design store led by Rossana de Marco, a member of the Chamber, opened in the Old City; Agustín Menini and Carlo Nicola inaugurated the industrial design studio, one of the most renowned in Montevideo; and the University of the Republic incorporated the graphic design career (…). All this, besides professionalizing the task, has generated a critical mass of public that identifies and consumes design, to which we should add an economic context that has allowed, in recent years, for the return of Uruguayans who were abroad and have a different visual culture, and the universalization of the social networks and access to online information”.59

Even if there are no specific data for the illustration sector, in quantitative terms, the available reports on the economy of culture indicate that the sectors of books and periodical publications, and plastic arts and photography, generate an added value equal to 26% and 5% of the GDP of the cultural product, which in 2012 was equal to 0.93% of the GDP.60 Between the activities of editing and publishing of books, newspapers, journals and magazines, a gross added value of more than US$ 81 million was generated in 2012, while in 2009 the total plastic arts market amounted to almost US$ 12 million.

Uruguay is characterized for being the Latin American country with the greatest book production per inhabitant. Although there exists a marked trend towards market concentration (one of the three most important multinationals concentrates 40% of sales), the country has a long tradition of independent or “boutique” publishing companies, which actively promote the emergence of new generations of writers.61 These publishers have achieved great regional prestige, distinguished by the originality and singularity of their productions. And even if there still are challenges in terms of the professionalization of the sector, its development has gone hand in hand with the offer of specific training courses for the sector, such as diplomas in edition, production and editorial design.

A dynamization of the contemporary art market can also be recognized, which is accompanied by a search for specific training, aimed at experimental production and the emergence of a new generation of professionals. In spite of this, there exists a high concentration of the activity (in 2009, 25% of the artists generated 70% of the income) and the most consistent nucleus of the local market is constituted by furtive buyers of works by renowned or “rediscovered” artists, in the context of the latest historical revisions, whose offer is concentrated in specialized galleries and auction houses.62

As an experimental or emerging art, graphic art has few specialized gallery owners and significant interlocutors. Unlike the great marchands operating in the international circuit, gallery owners in Uruguay do not specialize in the professional development of artists and their introduction abroad, which is paramount in such a reduced internal market.63 Their attitude is in general conservative - risk averse - and passive - devoted almost exclusively to selling - and so the visibility and promotion of graphic and emerging artists greatly depend on the spaces provided by state calls, the cultural services of foreign institutions and the private spaces of alternative nature.

Unlike the problems faced by contemporary Uruguayan artists,64 limitations to access the international illustration circuit are generally overcome by the ease of participation in the various events connected to it, such as fairs, congresses, contests or residencies. However, perhaps because of their performance in a comparatively small and still developing market, illustrators face challenges in terms of the promotion and negotiation of their works in the context of foreign legal and commercial environments. In this sense, there are challenges in the professionalization of the role of the illustration agent and the creation of associative strategies that promote the activity and the consolidation of the uses and regulations covering professional practice.

As a whole, both sectors employ a total of 5,471 people, with a high predominance of the book and publication sector (40% of the occupation of the cultural sector) over that of plastic arts. However, one of the historical characteristics of the cultural sector is its high level of informality, whether regarding the forms adopted by the employment of workers, or in the manner in which the business is carried out or the contents are accessed, especially given the proliferation of technologies which allow for reproduction at very low costs.

An example of this is that the law on the Statute of the Artist and Related Trades (No. 18.384), passed in 2008 to standardize employment and access to security in the performing arts, does not consider visual artists at any time. Experts have additionally pointed out that, as long as the remuneration for activities performed continue to be low, the workers themselves will have an incentive to remain outside the formal sector whenever possible, either to avoid paying taxes or because they are covered by social security through another main occupation. At the same time, there is also a strong tax and bureaucratic burden that limits the management of working capital in small companies, which finally opt for contracts which do not comply with the regulations.65

As summarized by Susana Dominzain: “in Uruguay, the cultural labor market turns to be - with some exceptions - not very profitable for the workers. Regardless of the cultural area they belong to and the geographic location they are in, most of them live off other jobs (...) Thus, while a selection of artists consolidate their income sources and their careers, others must develop their profession by performing other jobs and never get to receive the expected public recognition; in the technical sector that accompanies artistic work, people work freelance for long hours and it is difficult to achieve work stability; while the job of those who work in cultural management remains in an undetermined grey area, not forgetting that many times these roles are performed by the same people, authentic “entrepreneurs” of culture”.66

Another expression of the informality in the field of culture is associated with the forms of access to content, especially the role of copyrights. This problem became manifest in 2019, when the Senate rejected a bill to extend copyrights from 50 to 70 years (Act N.º 9.739). Without approving any changes to the current regime, the parliamentary debate addressed issues as diverse and relevant as access to cultural heritage and the right of access to culture, the regulation of publishing contracts to prohibit the abusive terms to which artists are subjected, the transparency of copyright collecting societies and their very high administrative discounts, the stock of assets of intermediary companies, and the urgent need to guarantee a solid social security for artists, allowing them to have health coverage and a dignified retirement.

Impacts and opportunities of the pandemic

In general terms, the impacts and opportunities generated by the pandemic in the illustration sector were framed both within the local trends and in the movements observed in recent years at a South American level, which is verifiable not only through in-depth interviews with qualified informants, but also through the several online discussions and forums that have taken place since March 2019. In line with the sector’s typical tensions, such effects may be linked to both the commercial activities or work carried out on commission, and to the areas of authorial production, including the action-art actions. However, these dimensions often coexist and feed back into each other, working as parts of a single phenomenon.

In the first place, illustration was affected by the cancellation of mass events and activities, such as theater and music shows, which generally demand significant visual and advertising production. This was, in some cases, compensated by the growth in the demand that occurred in the audiovisual67 or videogame sectors68 or by the institutions and commercial brands that employed graphic design and visual communication to spread public health messages, like stay home or keep physical distancing. There was also major digital development by many organizations, and new digital content was created to respond to the set of needs of the users that had to educate the children, keep connected, and socialize from their sitting rooms, stay physically and mentally well.69

Somehow, the impacts of COVID-19 reconfigured the model and the production processes of the design sector. The range of services offered was expanded and there was an increase in the use of remote access to repositories for distributed online work, as well as of the use of productivity and collaborative tools and applications (mural, slack, trello, asana, Monday, miro, etc.). Although these changes greatly depended on the kind of company (size, years in business and sector with which they were mainly connected), there has been a shift towards digital services that require graphic design and, consequently, the clients with whom they work have become more flexible.70

Although at the moment there are no aggregated or systematized data that account for such phenomena, the particular experience of Carolina Curbelo can be mentioned as an example: “despite the personal effects of the pandemic, these have been great two years for studio illustration, work commissioned for advertising, communication, at corporate and organizational levels. There was a high need for continuously communicating, and illustration is a good tool to communicate in difficult times, for example: to create animations of brochures explaining health measures in poor neighborhoods or to produce infographics and graphs with scientific information. Scientific illustration, in particular, had a very important boom, whether for articles, television news, YouTube videos and social networks. Demand grew to such point that there was an increase in the number of illustrators dedicated to these topics, and the experience and professionalization of the sector was boosted.”71

From Curbelo’s perspective, in a small internal market such as this, the activation of the demand brought about by the pandemic accelerated the professional careers of illustrators, because it implied their exposure and need to respond to an unusual amount of work demands. In many cases, this generated a fast learning of the quotation formats and methods, proposal presentation, project assembly and compliance with work deadlines, which otherwise would have occurred in a much longer term. This coincided, besides, with a generalized trend toward greater training, since the slowdown of the business situation in cultural and creative industries lowered the cost of opportunity of the training of human capital and many actors started to work towards diplomas, post-graduate degrees and specific training courses on themes connected with their activity.72

On the other hand, during the pandemic the editorial sector suffered the greatest crisis in many decades.73 During 2020, sales were down 25% from the average of previous years, and many launches were delayed and suspended.74 This blow was particularly hard for small independent publishing companies, who faced difficulties in meeting their commitments with printers and copyrights, as well as for children’s and young people’s literature, which represents 20% of national editions, and whose circulation and promotion generally occurs through talks and activities in educational centers or editorial fairs. In this genre, in particular, the pandemic also generated visible reflections around the need for illustration to adapt so as to include the context, in terms of feelings and everyday life in the new normal. To a certain extent, the recognition of illustration as a language of great communicational power that offers opportunities for the expansion of the inner world in times of pandemic becomes evident.

As described by Dani Scharf, recognized by Lürzer’s Archive as one of the 200 Best Illustrators Worldwide: “I used to be much more optimistic. Currently I have great uncertainty, which is part of the darkness that sometimes embraces me. I don’t know what will happen; I don’t know if anyone knows, and so I live day to day. I do know that this will affect behaviors and procedures (…) At times I doubt, and I fear, that such a stark reality will make our ongoing projects lose their validity. Is the children’s book I wrote before the pandemic and which is now ready to be published as broad and flexible as to absorb this context, and does its metaphor manage to include it? It really gives me great uncertainty. I have a series of produced and edited works. But they are all from before; none of them mention the pandemic.”75

In some cases, the impacts of the pandemic also gave way to new opportunities for innovation, such as the strengthening of virtual stores. Although these solutions could not emulate the type of cultural encounter generated in face-to-face spaces, the development of marketing and online strategies allowed some publishers to survive and even broaden their customer profile. According to the Chamber of Digital Economy of Uruguay, in 2020 many Uruguayan companies experienced a five to tenfold growth in their online channel, reaching turnover levels similar to those of brick-and-mortar stores.76 In line with the international trends,77 there was also an important boom of online auctions, traditionally devoted to the sale of art and antiques78 and a growth of the proactive use of Instagram and the different social networks for market positioning and the commercialization of works, both directly and through intermediaries.

Similarly, undertakings such as “Rastro: bazar del autor uruguayo” (an itinerating market that promotes local art in different manifestations and formats), “Microutopías: feria de arte impreso de Montevideo” (which seeks to exhibit and stimulate the independent production of publishers, collectives and graphic artists), or “Hungry Art” (a fully online gallery which offers works in “print” format), were consolidated. As Cecilia Gervaso, founder of “Hungry Art” (https://hungryart.art) narrates: “the gallery was uploaded to the Internet in the middle of the pandemic, after working on it for a year and a half. And, contrary to what one might think, the date was not unfortunate at all. The quarantine forced people to spend more time in their homes, which awoke their desire to transform them into a more pleasant place. This helped sales to be higher than expected”.79

Secondly, the illustration sector was highly affected by the cancellation of the editorial fairs, both traditional and independent. In the years before the pandemic, the Uruguayan artists actively participated in international events that opened up commercial and professional development opportunities, but the suspension of these opportunities implied that many of them had to transform their participation in person into other ways of exchange, participating in online courses, workshops, encounters, forums, and even artistic residencies. An example of this is the organization of the residency program “Inmersiones Irudika", held within the framework of the Encuentro Internacional Profesional de Ilustración en Euskadi (Spain), which in 2021 was completely virtual. That is to say that the selected Uruguayan and Spanish illustrators worked together in the production of the graphics for the next edition of this event through a blog.

The pandemic also promoted the organization of large cultural events in hybrid format (groups of 20 to 50 people are gathered in smaller face-to-face spaces and the event is presented digitally), which encouraged the participation among specialized intermediaries, the work in practice communities, and the creation of connections through chat, live streams and open virtual spaces.80 An example of this is the organization of the Festival de Ilustración y Literatura Expandida - FILEXPANDIDO (2020), the international fair of independent publishing and artistic experimentation that takes place in Salvador de Bahia (Brazil) and which in 2020 adopted a hybrid format and an open crowdfunding mechanism.

On the other hand, despite the fact that many international events were postponed, there was a phenomenon of strengthening and broadening of the pre-existing networks, as well of creation of new commercial and collaboration opportunities through the new technologies. Even though in many cases these new connections did not replace or surpass the links created in person, communication relationships through virtual means have become naturalized, both locally and internationally. This is especially evident in relation to the independent encounters and fairs, which are characterized by a strong anarchic position, questioning the power of the large publishing houses.

In South America, the independent publication or graphic art fairs (“feds”) are becoming more and more common. These encounters, which last between two and four days and gather a wide editorial diversity, seek to strengthen the publisher-reader link and boost the microeconomies connected to the world of books. As a response and alternative to the increasingly business-oriented profile that international fairs (“fils”) have been adopting, these events present themselves as a way of creating community (and not only reading community), of forging ties (and not only professional ties), and of building solidarity among agents of the cultural field, who are diverse although relatively similar in size.81 However, due to cost issues, many of these fairs tended to gather mainly those nearby, for which this “virtualization” generated by the sanitary measures somehow had a beneficial effect.

In some cases, the migration of the activities to the net made it possible to overcome traditionally existing barriers in terms of the costs of the transfers and the location capacity of the spaces, fostering the encounter of actors with similar interests who would otherwise not have been able to meet face to face, or who would have coincided in bilateral meetings and not necessarily for group reflection or exchange. These virtual encounters sometimes made it possible to burst the systemic bubble, incorporating new participants and audiences and promoting the planning of regional events and networking or collaborative work for the post-pandemic. An example of this is the initiative “Independiente de todo” (https://microutopias.press/independentedetudo), whose objective is the promotion of cooperation and the support of the independent sector during the pandemic context. In other cases, the cancellation of the international events caused the strengthening of some local circuits. Such is the case, for example, of the Microutopías fair, which in its face-to-face edition of 2021 only received representation from Uruguayan projects of printed art. As argued by its organizer, Darío Marroche, this made it possible to verify the existence of very elaborate projects, which indicates deep searches, collaborations among artists, experimental games, and multidisciplinary crossings that denote a clear consolidation of the sector (Figure 6).82

Finally, the pandemic exposed many social problems that already existed, renewing the role and potential of graphic expressions as insurgency tools. Secluded in their homes, many artists had time to reflect, resume their own projects, and deepen their authorial production, apart from commissioned works. In many cases, what happened is what Dani Scharf defines as a “greenhouse effect in which one’s own projects, and through virtuality, one’s connections with others blossomed”,83 the fruits of which - of a more experimental, interdisciplinary and powerful nature - are beginning to be observed only now in the networks, fairs and encounters. From this point of view, the sector has not stalled its development, has not come to a standstill, but in the frame of the pandemic, some of its facets have slowed down and eventually changed course.

Final remarks

Uruguay is a young country of modest physical and demographic scale that has outstanding artists of strong graphic tradition who have spread their seeds of talent and passion among the new generations. It is on these foundations that the new generations are currently making their way in the authorial search, in a sector that is empathetic with the public, but that, in turn, is always looking for means to make itself visible; to be able to say, resist and survive.

Although there is considerable scarcity in terms of the availability of data on the sector, it is also possible to conclude that Uruguayan illustration is anchored in a solid artistic tradition and a community that has been characterized by gathering around a common objective of "resistance" that strains the balance between the functional and social aspects of the discipline.

There are still important structural weaknesses surrounding the social, professional and economic status of artists, as well as of updated information on the opportunities and challenges in terms of the activity linked to cultural industries and the possibility of internationalization of local artistic production. However, based on the bibliographic and qualitative information gathered, it is possible to argue that there are public policies and private actions aimed at promoting the sector that - although lacking an apparent long-term strategy - have had successful results in terms of the visibility of the work of authors..

The players interviewed indicate, on the other hand, that for the Uruguayan artists and professionals who are used to looking beyond the limited national market, the time of the pandemic has allowed them not only to consolidate and professionalize projects, but also to receive increasing demand in several platforms and media, both physical and digital. In the pandemic scenario, distances appear to have been played down and many of the creators have dared to go out, to associate with others, to invite, to propose, to show themselves and explore outside the usual places and comfort zones.

In the immediate future, however, there are challenges that will require not only the advancement of existing weaknesses but also the development of new strategies for the positioning of artists in the artistic and commercial market. These challenges have to do, mainly, with the development of legal frameworks that establish parameters for the ethical use of new technological tools, especially with reference to artificial intelligence applications. From an optimistic point of view, it could be expected that the urgency of this context will force the resolution of the problems that have been afflicting the sector for the longer term.